Some time in the winter of 2017, Gary Gach reached out to a number of friends and colleagues about reviewing his -then in rough draft- forthcoming book. By mid-spring I replied that I would be very grateful to receive an advanced copy. And by June I was actually sitting down to read it over. As I told Gach by email early into my reading of the draft, “It’s direct, fluid, and wise; a beautiful mix of story-telling and dharma pushing.”

Some time in the winter of 2017, Gary Gach reached out to a number of friends and colleagues about reviewing his -then in rough draft- forthcoming book. By mid-spring I replied that I would be very grateful to receive an advanced copy. And by June I was actually sitting down to read it over. As I told Gach by email early into my reading of the draft, “It’s direct, fluid, and wise; a beautiful mix of story-telling and dharma pushing.”

Nearly two years later, and having received a review copy of and read the full book: the comment still stands.

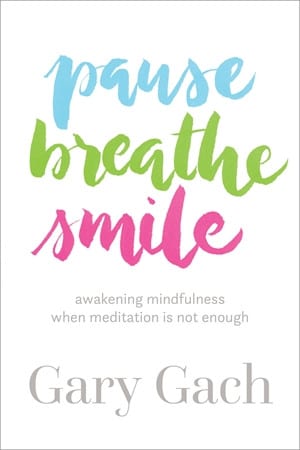

To say more, it is an ideal book for the committed beginner or the frustrated returner to mindfulness practice who wants to try again.

As Lynette Monteiro reflects in her review, “meditation is not many things we want it to be and it is not enough. When that becomes apparent, most practitioners give up and find another escape or addiction. Gach is not afraid to confront this head on.”

The book may also be valuable to Buddhists out there, seeking to see the different ways in which their tradition is being translated into the 21st century. The three sections: pause, breathe, and smile, map onto the traditional Buddhist path of morality, meditation, and wisdom (sila, samadhi, prajna).

The word discipline hangs in bold above page 19, after some introductory remarks.

discipline and mastery,

growth and freedom

With this, we have the start of a book about mindfulness that might even be appreciated by those wary of simplified and commodified versions of the practice. Likewise, we have a warning for those looking for a quick and easy fix. Not long after that, Gach begins his section on morality with a quote from American novelist and creative writing professor Maxine Chernoff:

A moral perspective is not the dessert course, added to the end of the meal and optional. We can’t be too rich or too poor to have one; it is the very core of how we live, how we get along with others, feel empathy for the plights of our fellow travelers, and try to shape our own lives and that of our children, loved ones, friends, and communities.

Following this, Gach offers perspectives on life, here and now, the foundations – the core – of the practices that will follow. This includes reflections on the golden rule, as found across traditions and societies, as well as the five Buddhist precepts (or ‘mindfulness trainings’ as described in the work of Thich Nhat Hanh). As Gach states, “Mindfulness trainings are voluntary, pragmatic, and relational. They resonate harmoniously with equivalents found in a range of spiritual traditions. Yet they’re bottom-up, rather than top-down. Lived experience rather than dogma or decree is their standard.”

The second section, breathe, skillfully covers well-worn ground on meditation techniques and attitudes. It is set off with the words of Thich Nhat Hanh: “Feelings come and go like clouds in a windy sky. Conscious breathing is my anchor.”

For me as a practitioner, this is the part of the book I enjoyed the most. Reading Gach’s flowing prose, I simply set off into his instructions, following the breath, “Mind becomes one with its object, so making life-giving breath the object of our mind it becomes our mind. Isn’t that worth a smile?” he asks. “Smile at your in-breath. Smile at your out-breath.”

Borrowing again from Monteiro, “Gach’s writing is full of amazing passages that both surprise and affirm what we already understand and feel. Yet, he takes us deeper: placing hands over the heart region during a meditation is like massaging compassion into our hearts. Never insistent in one way, he offers “a hundred ways to kneel and kiss the ground (Rumi)”.”

Gach’s repeated direction for the reader to return to the breath and this-moment awareness could be considered the heart of the book, and they will be what many practitioners return to again and again. But for engaged Buddhists and those more interested in the tradition as a whole, the first and third sections will be of equal, if not greater, value.

Third, we are instructed to smile, life’s not always what you think. Here we are introduced to important aspects of the Buddhist worldview, or philosophy (the wisdom aspect of the path). We are reminded in the words of Ajahn Sumedho, “Whatever we think we are, that’s not who we are.”

Wryly perhaps, Gach notes that, “The word wisdom, like the word ethics, might seem off-putting.” And yet, he notes, thanks to meditation some of the truths of reality make themselves ever more apparent in our daily lives. In Buddhist terms, one list of these truths is the three marks of reality: impermanence, unsatisfactoriness (Gach offers interconnection), and non-self or selflessness. What follows from this is a careful journey into some illusions of our lives and how we might, with practice grounded in ethical conduct, wake up from them.

Having begun with a call to discipline, Gach ends here with another aspect of the path that is often overlooked in self-help style books on mindfulness: community. He concludes with a question, “So then how much is being in community part of the practice?”

Answer, “It’s not a part of the practice, my friend. It’s really the whole of the practice.”

One can hope that all readers of Gach’s work take this seriously, seeking out communities in which to do the work of uncovering our illusions about ourselves and our world.

pause, breathe, smile is available at Sounds True.

please join our community of patrons for as little as $1/month