George Bernard Shaw once said “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.” And a not-too-old Guardian article re-ignited some debate, beginning with Oscar Wilde’s 1887 wrote, “We have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language.”

The differences, however, are not just between England and America. I currently live in Bristol, a city or area known as “The West of England” for some reason. If you ignore Somerset and Devon, both of which stretch west as they ease into the south, that works. I speak with people from around here, date a girl from up no’th and have friends from various parts of the country, all with their peculiar way of saying certain things. Bristolians, for instance, are famous for adding “L” to the end of words that end in a vowel. This goes back to… well, the origin of the name: Bristol. It once was Brigg stow; which in Saxon meant the meeting point at the bridge. At some point, over a thousand years ago, Brigg stow became Bristol. A more recent account comes from a BBC discussion board:

This led to a strange conversation I had once when I worked at a Builders Merchants, some bloke asked me “For Michael, tops?” I asked what is the surname? He said “No, Formica (L) Tops?” then I twigged, ahh Bristolian.

Conversations like this are common. I try to speak an “international English” when I’m here and people often tell me that I am easy to understand. But recently, after a friend from Montana visited, one of my Spanish friends caught me reverting to a bit of my own local-ism by saying, when I had misheard someone, “wha waz at?” (with the ‘a’s pronounced as in ‘up’, ‘up’, and ‘apple’). Oops.

And there are bound to be -isms in the English of any country, perhaps even many different sets. As the BBC reported recently, India has a few of it’s own Indianisms:

Prepone – To bring an event or meeting forward

Revert – to get back to someone

Only – added to the end of sentences

Out of station – Out of town

You’ve pulled down – You’ve lost weight

I’ll do the needful – I’ll do what’s required

They expired – They died

I’m going to office – articles routinely dropped

Usually such things are just a bit odd the first time we hear them, other times they can lead to a misunderstanding, and occasionally they can even be a bit controversial, as I found with the Americanized spelling and often (it’s debated) pronunciation of St. Paddy’s Day (traditional) as St. Patty’s Day (American). It’s not particularly new; the earliest printed version of St. Patty’s Day I could find dated to 1943. However, perhaps thanks to the internet, a movement has arisen -with it’s own website- to erase (or ‘correct’) this particular Americanism.

Yet while some people find these changes in language to be offensive or irritating, I tend to appreciate the varieties of human experience and expression. Business Insider recently published a number of maps showing differences in language in America. From my point of view, these aren’t maps to tell us ‘where they say things wrong’ but rather simple descriptive accounts. Many will confirm our suspicions, such as one that I grew up with, thinking that people in the South call a generic sweetened carbonated beverage a ‘coke’, while we in the North/Northwest call it ‘pop’ and folks from CA, the Northeast and some big cities such as Chicago and St. Louis call it ‘soda’. But the best ones are – to me – simply hilarious (you might have your own favorites):

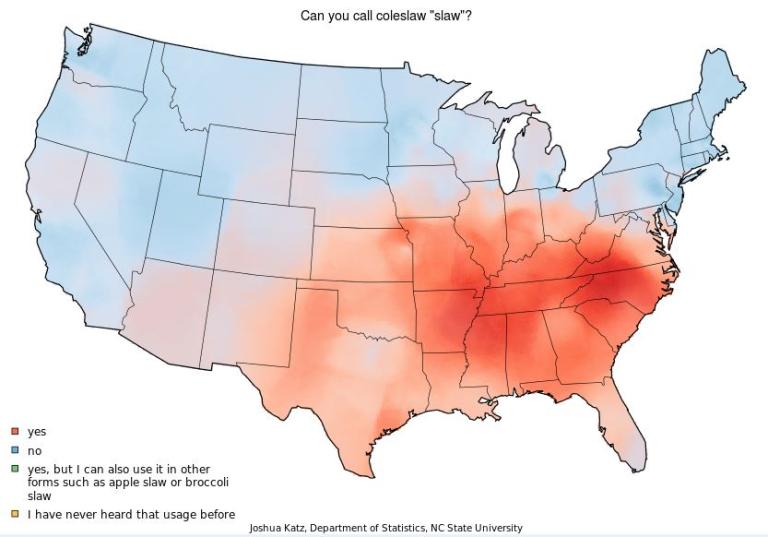

I like the simple yes/no character of this – and I’m a little bit worried about the idea of ‘broccoli slaw’:

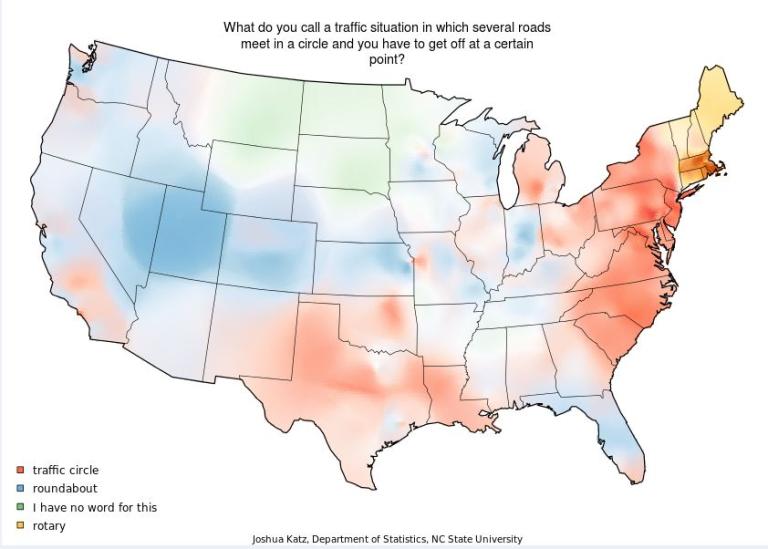

This one explains why I don’t drive in England (land of the roundabout). Where I’m from we don’t even have a word for these things.

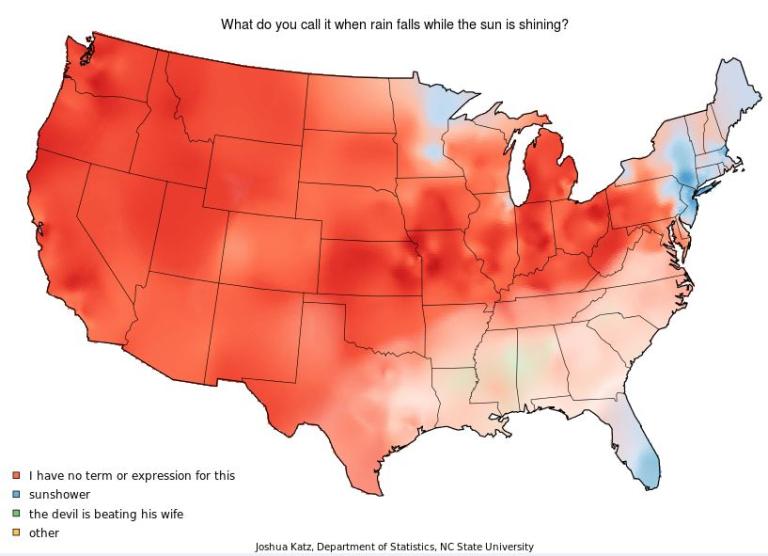

And my favorite, filed under ‘you learn something new every day.’ Can anyone from that area of Alabama/Mississippi or northern Louisiana confirm this?

See ’em all here.

Buddhisty Postscript: I suppose the “Buddhist” lesson here is that language points to something and it’s the something that matters – not the language or mechanism itself. The Buddha is depicted often as using his finger to point to the moon. He also told his monks to go out and teach in the language appropriate to each area they went to – while Brahmans (proto-Hindus) kept their scriptures in Sanskrit alone. I suppose we would say they were more concerned with the finger (than the Buddha was at least). Note also, later Buddhism did begin to adopt not only Sanskrit as a canonical language as well as the belief in the power of certain sounds/mantras.