“Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life. This results not merely from Life’s imitative instinct, but from the fact that the self-conscious aim of Life is to find expression, and that Art offers it certain beautiful forms through which it may realise that energy.” — Oscar Wilde, “The Decay of Living”

There has always been a close relationship between fantasy and contemporary Paganism, and for the most part, we Pagans are unashamed of it. Sarah Pike has documented the importance of fantasy literature in the religious development of many Pagans:

“Neopagans assume that there is a dynamic relationship between fiction and their own lives. They see their experiences reflected in Arthurian legend, J.R . R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, and ancient Greek myths. They react as if the boundary between fictional and real worlds is fluid, and their ritual work draws heavily on the fantasy novels and myths they are familiar with.” (Pike, Earthly Bodies, Magical Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community)

Much of the Pagan revival itself was inspired by fantasy literature. As Ronald Hutton has documented, Dion Fortune’s fiction, especially The Sea Priestess and The Goat Footed God, was an important influence on British Traditional Wicca. As was Robert Graves’ White Goddess — which is a work of imagination in the guise of philology.

The American Pagan revival was also inspired by fiction. Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land inspired the creation of the Church of All Worlds, which quickly became a centripal force on the newly emerging Pagan movement. Today, Valentine Michale Smith’s declaration, “Thou Art God/dess,” is a familiar refrain among Pagans, even those with no association with the Church of All Worlds.

Graham Harvey has discussed the significance of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, which “opened the way for a revalidation of belief in fairie” and also “sent people back to the traditions of Ireland, Norway, Britain and elsewhere to find more ancestral understandings.” Harvey explains:

“Academic literature is undoubtedly important in the construction of Paganism*, but Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and other fantasy writings are more frequently mentioned by Pagans. Fantasy re-enchants the world for many people, allowing them to talk of elves, goblins, dragons, talking-trees, and magic. It also encourages contemplation of different ways of relating to the world, the use and abuse of power (especially as expressed in and by magic), and issues of race, gender and sexuality. It counters the rationality of modernity which denigrates the wisdoms of the body and subjectivity. Alongside Future Fiction, the genre explores new and archaic understandings of the world, and of ritual and myth, and attempts to find alternative ways of relating technology to the needs of today.” (Harvey, Listening People, Speaking Earth)

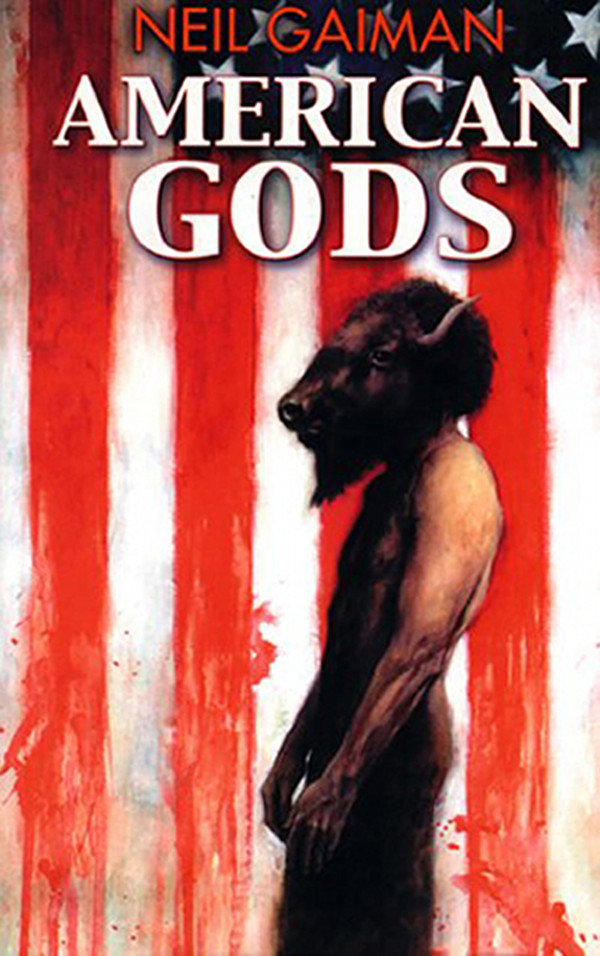

Recently, Sable Aradia posted a list of 22 novels that popularized and influenced Paganism, including Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, Terry Pratchet’s Discworld series, Anne Rice’s Mayfair Witches series (my entre to Paganism) … and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods.

None of this has ever been particularly controversial that I am aware of.

Like Harvey (above), I believe that contemporary Paganism was “constructed” — rather than being revealed from on high like the Abrahamic religions claim about themselves. It may have been a hodgepodge construction, but it was a construction nonetheless. And an important part of that construction was fiction.

But saying that works of fiction played an important role in the Pagan revival does not deny that it was inspired by powers which transcend the minds of the authors of those works of fiction — whether those powers be the Goddess, the Gods, the Collective Unconscious, the Muses, or what have you. Saying that the Church of All Worlds was inspired by Stranger in a Strange Land does not deny that it was also inspired by Oberon Zell’s prescient vision of the earth as a single living organism. Saying that Frederick Adams, the founder of Leraferia, may have been inspired by Tolkien does not deny the importance of Adams’ own visionary experience of the Divine Feminine. And the fact that The Witching Hour played a role in my coming to Paganism does not deny that transcendent archetypal powers were working through that book.

My interest in the influence of fantasy literature on Paganism is part and parcel of my abiding interest in the history of ideas. When I became a Pagan, I was at least as interested in how contemporary Paganism had evolved, as I was in what it had evolved into. It’s no coincidence that my first “Pagan” book was Ronald Hutton’s Triumph of the Moon. Knowing the history of a religious movement does not invalidate it, in my mind. Rather, it adds to its richness.

So when I suggested that “Neil Gaiman’s American Gods may have played a role in the growth of deity-centered Polytheism”, I was not attempting to “erode” or “demolish” devotional polytheism.

I do sympathize with those hard polytheists who find the connection to be upsetting. Hard polytheists often find themselves defending their literalistic belief in reality of their deities, even among other Pagans, who may take a more nuanced view of gods. Because the contemporary manifestation of devotional polytheism is a relatively new movement, even among Pagans, and a relatively small one in relation to the world’s religions, hard polytheists may feel themselves particularly vulnerable to anything which might undermine the credibility of their religion. And so the association of devotional polytheists with a work of fiction can be interpreted as an attack on their beliefs, especially when made by someone like me, who has been critical of literalistic forms of polytheism.

Having said that, an acknowledgment of the influence of human culture on our religions need not be perceived as an attack on the legitimacy of those religions. To say that American Gods played a role in the growth of devotional polytheism is not to say that the gods of devotional polytheists are not real, nor is it to say that their gods originated in a work of fiction. A work of fiction may open a person up to having a very real experience to which they were not open before. For example, a person might read American Gods and develop an interest in devotional polytheism, from which they proceed to learn more and seek out a direct encounter with the gods. As Julian Betkowski has observed,

“Many Pagans have spoken of the role of literature in their coming to Paganism. The books that we read as children, science fiction and fantasy, informed the ways we relate to the world, and when we found Paganism, well, for many of us it was a homecoming. … Books plant seeds. When we read, we open ourselves up a bit to the strange influence of others ideas, and they lay dormant inside of us.”

Or perhaps Gaiman simply tuned into the Pagan Weltanschauung, but in doing so amplified it. Even if we assume that the gods themselves are independent causal factors in the growth of devotional polytheism, we can’t ignore the role of human agency and cultural context. The gods do not act in a vacuum any more than human beings.

In Part 2, I will discuss the significance of American Gods for understanding the growth of devotional polytheism and dynamics with Paganism generally.