“We don’t need a ‘change in spirit’. This is not on ‘us’. The vast majority of damage to the planet is done by megacorporations or state power, not individuals. If you don’t set your gaze on them, you can try to change people’s spirits all you want but we will still be doomed.” — Alley Valkyrie*

The comment above was made during public comment period on the draft of “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment” (which is still open for comment until April 22, Earth Day). Alley and Rhyd Wildermuth are the authors of “A Pagan Anti-Capitalist Primer”. Their perspective on the evils of capitalism is inspired by Marxist thought. The end of the Primer recommends the writings of Marxists, Murray Bookchin and John Bellamy Foster, as well as popular critic of corporate globalization and of corporate capitalism, Naomi Klein, author of “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate”.

Alley’s comment was in response to part of the draft Statement which reads:

“In addition, there is a deeper and more profound change that is needed. Fundamentally, we believe that a change in spirit is required, one that fosters a new relationship between humanity and other species and Earth as a whole.”

Alley’s entire comment is too long to quote here in its entirety, but here some more context:

“… I also wince at the stressing of ‘sustainability’ as the path out of this. Sustainability is BS, sorry. ‘Green capitalism’, ‘conscious consumerism’, all these things are tricks, traps, things to make us feel good and further distract us from the harm that we’re doing. Recycling, PV cells, eco-bulbs, these things harm much more than they help. Do the research. I find such assumptions to be dangerous, frankly. We don’t need a “change in spirit”. This is not on ‘us’. The vast majority of damage to the planet is done by megacorporations or state power, not individuals. If you don’t set your gaze on them, you can try to change people’s spirits all you want but we will still be doomed.”

As I’ve written here before, I am in agreement that our economic system is fundamentally incompatible with a healthy planetary ecosystem. We live on a planet with finite resources, but our economic system is premised on infinite growth. And since we can’t change the laws of nature, we must change our economic system. This means challenging some of our most cherished myths: the myth that capitalism and democracy are equivalent, the myth that capitalist societies are the most happy, the myth that capitalism was proven to be the “one true economic system” with the fall of the Soviet Union, the myth that consumers have all the power in a capitalist system, and that most pernicious myth of all, the myth that things must always be the way they are now.

But in spite of my general agreement with Alley and Rhyd, I disagree with Alley’s statement above about the futility of spiritual change.

I’ve always been an idealist. I don’t mean that I am an optimist. I mean it in the philosophical sense, as in philosophical idealism. As a philosophical idealist, I tend to think that ideas are what makes the world go round. The philosophies of the German idealists, Hegel, Fichte, Schlling, and Schopenhauer (and those they later inspired) appeal greatly to me, and I have an abiding fascination with the history of ideas and the intellectual history of the world. (No doubt, my philosophical idealism is related to my solipsistic personality.)

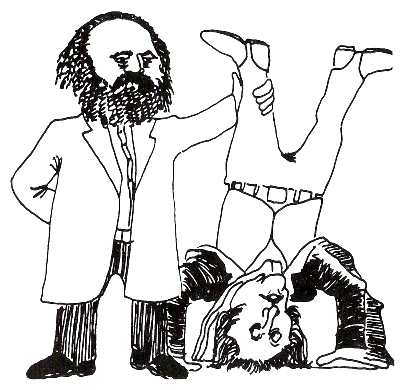

If you took a philosophy class in college or have read an introductory book on Western philosophy, then you may remember hearing or reading how Marx “flipped Hegel on his head”. Marx was a historical materialist, which means that for him, matter, not ideas, is what makes the world go round. For Marx, what he called the “superstructure” — which included culture, religion, philosophy, art, etc. — were secondary to the “material forces of production”. So, while Hegelians would say that, in order to change the economy, you need to change people’s minds, Marxists would say that in order to change peoples minds, you need to change the economy. (Of course, this is an oversimplification, but you get the idea.)

Since becoming Pagan, I have drifted a little more toward the materialist conception of the world. Pagan ritual has taught me how physical movement can alter my state of mind. And right now I am reading The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding by Mark Johnson, the thesis of which is that all of our thought and language emerges out of our experience of physical embodiment.

Still, I’m not quite ready to declare myself a Marxist, and here’s why …

Being Pagan has also taught me:

- to be skeptical of hierarchies of all kinds

- to privilege circular dynamics over linear ones

- to favor both/and answers over either/or answers

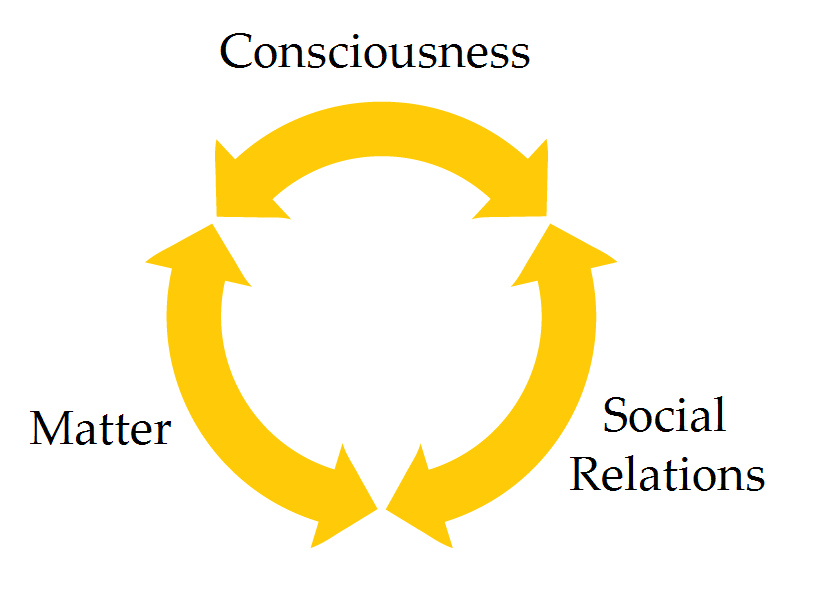

Thus, rather than flipping “Hegel on his head”, which just perpetuates the hierarchical and linear thinking, a more “Pagan” response might be to imagine our material conditions, our social relations, and our modes of consciousness existing not in a hierarchical relationship, but in a circular one. What this means is that there is no single solution to our planetary ecological crisis. And there is no single point of entry for addressing our problems.

We have an unsustainable system of resource extraction and consumption, which is rapidly making the earth uninhabitable for human beings, as it has already been made uninhabitable for countless species. That system is built on an economic model — global capitalism — which has failed in all of its promises. And that economic model is built on a spiritual hegemony which alienates human beings from the material source of our being and from all life. I believe must attack this cycle at all of these levels.

This idea has been written about in many ways, and is referred to as “points of intervention” or “leverage points”. We can and should work to change this system at all of these levels. For example, we can intervene at the points of production and destruction by protesting at a factory or blocking a logging road. We can intervene at the point of consumption, by changing our buying habits and convincing others to do the same. We can intervene at the points of decision, by petitioning our legislators or running for office. And we can intervene at the point of assumption, by working to change foundational narratives of Western culture.

It is in this last area that I believe Pagans have the most unique contribution to make to this fight. We can lead the way in effecting paradigm shift away from from a mode of consciousness which is linear, atomistic and disenchanted — which lies at the root of all of these failed systems — to one that is cyclical, interconnected and re-enchanted. One way we do that is through ritual’s which connect us to nature and by creating new myths, like the myth of Gaia. Another way, is by taking a public stand like that articulated in by “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment”.

So, I agree with Alley that working toward a shift in consciousness is not sufficient by itself. But likewise, neither do I believe that changing our economic system will be sufficient by itself. A socialist economic system can be destructive to the ecosystem too, if there is not a corresponding change in consciousness. We must work toward change at all of these levels simultaneously. I agree with Alley when she says, in another comment, “We need to be deeply critiquing the way that we live at every intersection, both physical and metaphorical.” — because for me the “metaphorical” implicates the spiritual. As much as a change in economic systems, we need a change in spirit. As the ecologist, Paul Shepard, says: we need

“nothing less than a shift in our whole frame of reference and our attitude toward life itself, a wider perception of the landscape as a creative, harmonious being where relationships of things are as real as the things. Without losing our sense of a great human destiny and without intellectual surrender, we must affirm that the world is a being, a part of our own body.”