From Self-centric Paganism to earth-centered Paganism

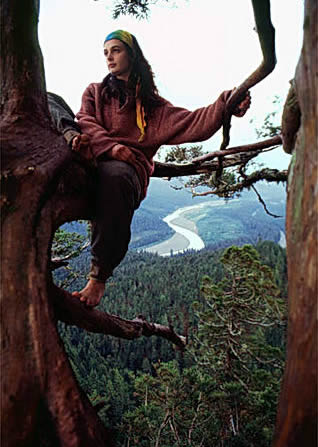

“If you want to go live in a tree, just let me know.”

That was my wife’s recent response to my awkward attempt to tell her about the spiritual/emotional/psychological transition I am experiencing recently. From someone else, I might have taken offense, but I knew she meant it. That’s my wife — supportive and pragmatic. She’s always been a “where the rubber meets the road” kind of gal.

It’s hard to put my finger on where it all started. But over the past eight months or so, since Pantheacon, I have felt my spiritual orientation shifting from a mostly Self-centric practice to an increasingly earth-centered practice. Actually, that statement is really misleading, because it implies that the two are different things. This paradigm shift I am experiencing is more like the realization that Self and earth are not two things — something I’ve understood intellectually before, but am really experiencing now. I was aware, in theory, that a Self-centric practice could lead to an earth-centric one, but now I’m living it. It may seem counter-intuitive, but while Self-centric Paganism does lead “within”, ideally the path into the depths of one’s soul opens up on the other side to the world. I think I’m starting to push through to the other side finally. I guess deep ecologists call this the realization of one’s eco-self, ecological self or “more-than-human self”. But those are just words. The experience is something else altogether.

Stepping Stones Toward Eco-Consciousnes

Stepping Stones Toward Eco-Consciousnes

Several events have helped push me along my way, including …

- Around the time of Pantheacon this year, I was able to finally release my preoccupation (obsession?) with devotional polytheism and articulate what I think I had been grasping for but not finding there, which was a devotional practice with the earth at its center,

- a camping trip in July with my family at the “Garden of the Gods” in southern Illinois had a restorative effect on me, as the rolling green hills only can,

- a visit later in July to Pando, a grove of aspens located in central Utah that is the largest living organism on the planet, where my wife led me and her largely Mormon family in a simple ritual, followed by a night in the mountains, during which we observed the Milky Way reaching from horizon to horizon,

- (oddly enough) the release of the movie Lucy, which I saw in early August, and which has nothing to do with the environment on its face, but is about a profound a shift of consciousness toward what I would describe as identification with the cosmos, which I sympathetically experienced after watching the movie,

- the release of the Covenant of the Goddess’s statement on the environment in August, which prompted me in early September to organize a group to create a Pagan Community Statement on the Environment (the group is now organized and hard at work),

- through my effort to round out the essays on the Neo-Paganism.com site with more earth-centered material, my discovery of the writings of John Muir and the story of Rachel Carson, which inspired me to go on an (ongoing) exploration of deep ecology, which is documented in part here in my Deep Ecology Tree series which lasted through September and October, and

- the People’s Climate March in September, which I participated in locally, and which corresponded with a growing sense of urgency within me about impending environmental disaster,

- all of which culminated in a mild depression — which I now understand is not uncommon among those cultivating an “eco-self” (see here and here and here).

It’s been a busy year. And then there was the smell of burning leaves on the crisp autumn air last week. And the taste of raspberries from the plants in my backyard, and some of the last tomatoes from my garden. And the sound of wild geese flying south, “announcing my place in the family of things.” And dozens of other “ordinary” experiences, which I have a tendency to leave out. I can be overly cerebral when I reconstruct important events in my life and leave out these visceral experiences, which are at least as important, I think.

“We are already living in a tree.”

All of this culminated in my attempt to explain this shift to my wife the other day. “If you want to go live in a tree, just let me know,” she said. I didn’t know how to respond at the time. Later, as I reflected on it, I thought, “We are already living in a tree.” I think that insight might sum up the shift in perspective I am experiencing.

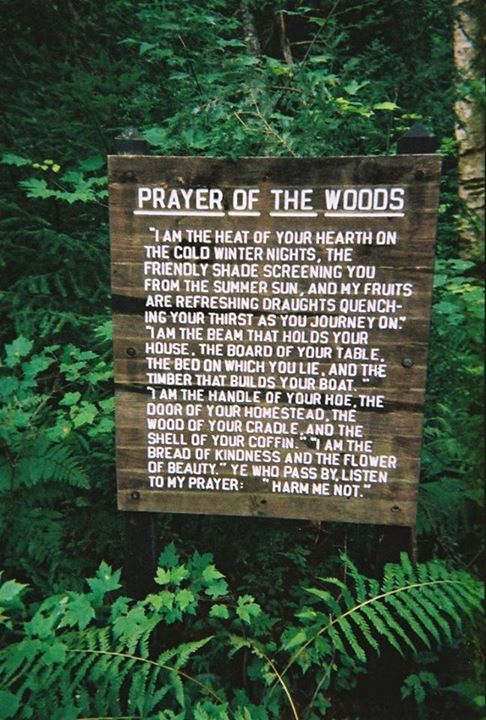

I suppose one might take a statement like that metaphorically, I meant it quite literally. We are already living in a tree. Not in the way Julia “Butterfly” Hill lived in a tree, but in another, no less literal sense, I think. Our house is made of wood … and thus, of trees. The floors we stand on are made from trees. The walls are framed by wood from trees. The roof built of wooden beams and planks from trees. In a very real sense, I am living inside of trees.

You may find that statement obvious … mundane and pedantic even. But to me it seems profound, because it really isn’t obvious to me, not in the course of my day-to-day life at least. You see, I live in the illusion of separateness from nature … an illusion created by artifice. I am surrounded by “artificial” objects and structures that don’t seem to be a part of “nature” — but they are. Even the ubiquitous plastics ultimately originate from organic sources, and even inorganic metals are part of the earth. All of this is “nature” … even me. Even my body. Even my thoughts and feelings are grounded in the electrochemical reactions of my brain, heart and gut.

“Living what is not life”

But that is not my ordinary way of perceiving reality. Even though I don’t believe it, I still move through the world as if I were a “ghost in a machine” and the world just a collection of objects “outside” of me. I am coming to believe that this illusion of separateness is crafted and maintained deliberately — not by a cabal of Illuminati in smoke-filled rooms, but by all of us, individually and collectively, in an effort to avoid the ineluctable fact that we are all going to die someday.

We hide from ourselves our immersion in nature. We do this by surrounding ourselves with artifice — things which are nature, but appear to be otherwise. So much so that I can forget that I am already living in a structure made of trees, that something died so I could have shelter. Just as I eat prepackaged food so that I forget that something died to sustain me. I do this so can bury a little deeper the knowledge that I myself will die and be someone else’s food — and perhaps millions of years from now be a part of someone else’s shelter.

The trick is to keep this knowledge — this feeling — in the forefront of my mind, to resist the inertia of existence which forces it into the background. That’s been hard. I’ve been struggling to resist the draw of distractions which seem to place invisible barriers between me and that experience of participation. “I did not wish to live what is not life,” Thoreau famously wrote. What insight is in that simple statement: that it is possible for human beings to live what is not life … and that this should be the most ordinary of things for us, that we must actually exert effort to do otherwise!

And when I manage to hold it, then comes the really hard question … how to live with this knowledge? What does this mean for my day to day life? — that’s what my wife wants to know. One of the commenters to another post tells me it’s all futile and that my use of a computer to blog about this makes me a hypocrite. Selectively changing individual consumption habits may not avert environmental catastrophe brought on by global warming, but are there other reasons to change? I think there are. I think about that story of the boy and the old man on the beach and I think, perhaps it is not a question of our saving the lives of all the starfish or even of individual starfish, but of the starfish saving our lives. Perhaps there is no better reason than that I no longer want to live in a world that has had all the life methodically sucked out of it, a sterile world of things and not beings. Perhaps there is no better reason than that fleeting, but very real feeling of being a temporary knot in the immense web of life, a feeling that I think jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was describing when he said:

“Life is a roar of bargain and battle, but in the very heart of it there rises a mystic spiritual tone that gives meaning to the whole. It transmutes the dull details into romance. It reminds us that our only but wholly adequate significance is as parts of the unimaginable whole. It suggests that even while living we are living to ends outside ourselves.”