“Blessed is the day when the youth discovers that Within and Above are synonyms.”

Emerson, journal, Dec 21, 1934

The Eldest Tribe of Gods

“Heaven walks among us ordinarily muffled in such triple or tenfold disguises that the wisest are deceived and no one suspects the days to be gods.”

Emerson, letter to Margaret Fuller, 1840

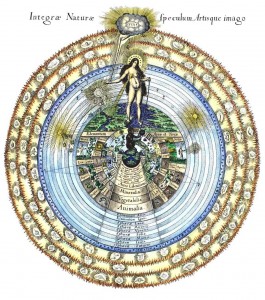

In my last post, I wrote about my gods, or more specifically, half of my gods, the gods of the microcosm, the gods of my human psyche. In this post, I want to complete the picture, by descrbing the gods of the macrocosm, of the natural world, as I experience it. It is to author and liturgist, Steven Posch, that I am indebted for this vision of a non-anthropomorphic natural polytheism.

“The late summer thunderstorm was beating down on us fast. In unearthly silence–the thunder still too far away to hear–the livid northwestern sky juddered with lightning. But in the circle around the bonfire, no one was thinking about the storm. The business at hand was the evening ritual: something to do with (I kid you not), community, popcorn, and the festival organizer’s most recent art project. Thoroughly bored, I watched the storm approach. ‘A god is coming,’ I thought, ‘and we’re too busy doing a ritual to even notice.'”

This is how Steven Posch begins his Autumn 2009 Pentacle article, “Lost Gods of the Witches”. (Posch is the author of a book by the same name, which sadly I have been unable to lay my hands on.) Posch’s article is a call for a “genuinely contemporary articulation of pagan experience”. He takes aim at the three primary forms of contemporary Paganism: Wiccan bi-theism (“half way to monotheism”), Neo-Pagan eclecticism (“a rimless wheel made up of rim and spokes only”), and reconstructionism (“purist ghettos of nostalgia-driven renactors”). Posch finds none of these satisfactory. We need to (re-)learn how to be “natives of here and now,” Posch writes, “pagans for our own time, our own place, our own post-modern, science-driven, Western culture.” To do that we must encounter the sources that inspired the ancient pagans in the first place: the natural world in all its multiplicity. We must make the “radical leap out of our own internal dialogue and into actual relationship with real, non-human others”.

This is how Steven Posch begins his Autumn 2009 Pentacle article, “Lost Gods of the Witches”. (Posch is the author of a book by the same name, which sadly I have been unable to lay my hands on.) Posch’s article is a call for a “genuinely contemporary articulation of pagan experience”. He takes aim at the three primary forms of contemporary Paganism: Wiccan bi-theism (“half way to monotheism”), Neo-Pagan eclecticism (“a rimless wheel made up of rim and spokes only”), and reconstructionism (“purist ghettos of nostalgia-driven renactors”). Posch finds none of these satisfactory. We need to (re-)learn how to be “natives of here and now,” Posch writes, “pagans for our own time, our own place, our own post-modern, science-driven, Western culture.” To do that we must encounter the sources that inspired the ancient pagans in the first place: the natural world in all its multiplicity. We must make the “radical leap out of our own internal dialogue and into actual relationship with real, non-human others”.

Sun, Moon, Earth, Storm, Sea, the four Winds, Fire, Red/Horn, and Green: These are the ones which Steven Posch (and Melanie and Chris Moore) call “the Eldest Tribe of the Gods”. These are the Gods who came before the Younger Gods, the anthropomorphic deities of historic pantheons, the gods of war and goddesses of love. Steven numbers them Twelve, but he also names others: Sky, River, and Mountain. There are others no doubt: Water, Dirt, Blue (Day Sky), Black (Night Sky), and more still. These are, I think, what Robert Browning called, “The hidden forces, blind necessities, Named Nature” which preceded what we are used to calling “gods”:

I saw that there are, first and above all,

The hidden forces, blind necessities,

Named Nature, but the thing’s self unconceived :

Then follow, — how dependent upon these,

We know not, how imposed above ourselves,

We well know, — what I name the gods, a power

Various or one: for great and strong and good

Is there, and little, weak and bad there too,

Wisdom and folly : say, these make no God, —

What is it else that rules outside man’s self?

They are what the Cambridge Ritualist, Gilbert Murray, called, “Gods or forms of God: not fabulous immortal men, but ‘Things which Are,’ things utterly non-human and non-moral […]”.

This is a polytheism that is consistent with a philosophical naturalistism as I understand it. No belief is required for these gods, writes Posch. They are “real” beings with whom we are always already engaged. (By “real” I understand him to mean “tangible”.) Their relationships with each other and with us are also “real”. Sun, Moon, Earth, Storm, Sea, Wind and all the others: these are engaged in an elaborate dance, and we take part in that dance with every breath we take. Posch calls this the “hardest polytheism”, as hard as rocks. This is a polytheism which is consistent with a scientific worldview. Indeed, says Posch, we are able to learn about the gods themselves through science.

Posch admits that this is a redefinition of “god”. These are neither anthropomorphized ideas nor archetypes. He leaves open the question of whether the gods are sentient, but suggests that, if they are, it is not in the same way that we are. Perhaps, we ourselves are the self-awareness of nature, he writes; ours are the eyes through which nature perceives itself. But regardless, what matters, says Posch, is that they are real and their relationships with us are real. Prayer and offerings are the metaphors that express those relationships, writes Posch, and it does not matter that they do not hear the prayers.

As Without, So Within

“I want to know, why beauty exists, why nature continues to contrive it, and what is the link between the life of a lightning storm with the feelings these things inspire in us? If God does not exist, if these things are not unified into one metaphorical system, then why do they retain for us such symbolic power?”

— Anne Rice, The Vampire Lestat

So these are my other gods: earth, sky, sun, moon, night, star, tree, water, air, dirt, wind, greenness. These are not abstractions (which is why I have not capitalized them like Posch). They are always this sky, this sun, this night, this tree: the one right in front of me, right here, right now.

What then is the relationship between my inner and outer pantheons? This is a question Browning poses in the poem above: “Nature […] Then follow, — how dependent upon these, We know not, […] what I name the gods”. What is the relationship between the gods of my psyche and the gods of nature? They are not the same, but the are connected, connected through me. The morning sun rising in the east and the Bright Youth are not the same, but the sun I see through my window in the morning does call to the Bright Youth in me. And the Bright Youth responds. The full moon calls to the Muse, and the waning and dark moon to the Dark Maiden who is a part of me. The earth I touch with my fingers calls to the Mother, in both her guises, Nurturing and Devouring. The bright green shoots rising from the earth and the green leaves on the trees on my street in the spring, these call to the Stag King. The red leaves fallen to the earth in the autumn, these call to the Dying God. The spring storm that rises up suddenly in the west calls to the Storm King. The night sky, the dark space between the stars, calls to Mother Night, my death come to make peace. The very passing of the seasons calls to the gods within me. The Sun Child and Mother Night in the winter. The Stag King and Lady of the Beasts in the summer. The Dying God and the Manslayer in the fall. The gods-without call and the gods-within respond.

These are not anthropomorphications. I do not project my inner Lightbringer onto the sun. The sun is still the sun, an unimaginably large flaming ball of hydrogen a hundred million miles away whose light is filtered through 10 miles of atmosphere. But when I face the sun in the morning and raise my arms and recite a prayer inspired by the Rig Veda, I am speaking to that sun in the sky and to the Sun/Son within me. They are not the same, but the former calls to the latter and I respond with these words:

Scaling heaven, splendor encompasses you.

Chariot-borne, sun-bright, and truly potent,

You pour forth, bursting the clouds,

Giving life to Sun and Dawn.

I am a clearing where the gods within and the gods without meet.