Controversy has broken loose on the Pagan blogosphere again. This time over the suggestion that pop culture icons, like comic book superheroes, are equivalent to polytheistic deities. It began on May 13th with a post by Sunweaver at Patheos titled “Making Light: Hero Worship” in which she compares contemporary superheroes to ancient Hellenic heroes and then a response by Norse Heathen Galina Krasskova’s who argues that unlike superheroes, heroes were real people.

Subsequently, dozens of bloggers and hundreds of blog commenters have jumped into the fray. Much of the debate appears to be taking place on Tumblr. There have been too many responses to summarize here.

What this discussion has revealed to me is the diversity within the polytheistic community. I have previously written about the Pagan community in term of three overlapping circumferences: deity-centered, Self-centered, and earth-centered. This debate has made clear to me that there are significant differences within each of these three groupings.

I realized this upon reading Canaanite Reconstructionist Tess Dawson contribution to this debate, “We Are Not All One. And It’s OK.”. In her post, Dawson argues that there is a fundamental difference between (what she perceives as) “mainstream neo-romantic Paganism and historic-rooted polytheistic religions” and we should stop trying to treat these two groups like they belong under the same umbrella:

“Neo-romanticist Pagans who believe that the self is the core of spirituality and who rely on the ideas of Jung, Freud, Frazer, and Campbell are often going to feel picked on when they believe that someone has told them that they’re wrong—especially when they believe that an individual person cannot be ‘wrong’ about spirituality. And it’s likely that they’ll think that the other person is so clinched in dogma that he/she just doesn’t understand what real spirituality is. Likewise a person who adheres to a historic-rooted polytheistic religion (not a spirituality, but a religion) is generally going to believe that worshiping archetypes or comic book superheroes is blasphemous.”

The two groups, says Dawson, are as different as Christianity and Hinduism, and both sides need to stop trying to convince the other one they are right:

“The two core philosophies cannot be resolved and the less time we spend trying to convince each other that our side is right, the more time we can spend constructively and peacefully on interfaith efforts. I use that word ‘interfaith’ with great intention. We’re not the same religions. We’re not even in the same category of religions. And that’s ok. Respecting our differences is important because this respect does not come from trying to make the differences into similarities. Respecting differences doesn’t mean homogenizing diversity.”

I agree with Dawson about the differences between earth-/self-centered Paganism and deity-centered polytheism. The problem with Dawson’s analysis, though, is that not everyone fits well into either one of these groups. I’ve noticed that polytheistic reconstructionists like Krasskova and Dawson assume that everyone who does not agree with them must be a Jungian/Campbellian archetypal-type Pagan. But that is not true of many or even most of the Pagans who have joined this discussion. In fact, Sunweaver, whose post started this debate, does not fit neatly into the Jungian archetypal category. She writes:

“They are my gods. I speak to them, I feel their presence, I know from experience that they are Real. They are not real to me like Samwise Gamgee is real. They are real to me like my cat is real, but they often speak to us in metaphor and story.”

This issue reveals much about the diversity within Paganism. Those who have responded to this debate seem to fall within one of five broad categories:

1. Deity-centered polytheistic reconstructionists

2. Non-reconstructionist deity-centered polytheists

3. Self-centric magickal Pagans

4. Self-centric archetypal Pagans

5. Non-theistic earth-centered Pagans

(In what follows, I place various responses in one of these categories. If you feel that I have mischaracterized your, your beliefs, or your writing, I apologize. Please feel free to comment and let me know.)

Deity-centered polytheistic reconstructionists

These individuals value personal interaction with gods. (I am using “gods” here broadly to include heroes and ancestors although these are distinct categories to polytheists.) They insist that their convictions are a matter of experience, not belief. They emphatically maintain that the gods are “real”, but they usually do not explain what this means, other than to insist that the gods are not created by us and they exist independently of our minds. I have noticed that this group often seems threatened by any question about the ontological nature of the gods. They also are insulted by Jungian/archetypal explanations of deities, and they find the comparison of gods to characters from pop culture to be impious. For this group, religion is not about self-improvement; it is about honoring, serving, and expressing devotion to the gods. Reverence, piety, and devotion are defining values from reconstructionists.

A good representative example of this group is Norse Heathen Galina Krasskova, whose post “Heroes vs. Superheroes” helped set this controversy in motion. Krasskova responds to Sunweaver, arguing that, unlike superheroes, heroes were real people. But, as Christine Hoff Kraemer points out in her post, hinging the argument on the historicity of heroes is problematic “because as we know well, the relationship between the tales told of historical people and the historical reality often diverge wildly within even a few generations.”

Another good example of the poly-recon group is The Anomalous Thracian‘s post, “My Gods Are Not Characters”. (Anomalous describes himself as more of a historically-informed polytheist than a strict reconstructionist.) He (rightly I think) points out the similarities between reconstructing a religious practice and writing fan fiction:

“… we do not (as lay practitioners or professional clergical figures) have the benefit of unbroken living lineages or traditions to draw upon; these are either new religions based on old ones, or attempts to reconstruct ancient traditions or religious paradigms in the modern world from our reflective (and/or academic!) understanding of them. Many of us are effectively ‘authors’ of new (or newly returned!) religious patterns of behavior, thought, or engagement. Since we are generally generating these ‘authored ways’ in conjunction with other people, we are doing so in a ‘shared world’ environment not dissimilar from series television script writers, comic-book authors writing for ongoing monthly titles, and so forth. In other words we are not necessarily wrong in noting the (figurative!) similarities between building (or rebuilding) religions and either the professional writing of shared-world fiction settings, or the amateur reading of them.”

But, then Anomalous does a one-eighty and proceeds argue that there is a difference because the gods are real: “the gods and spirits I engage with are real, literal beings, not ideas or concepts or archetypes or thought-forms.” But he fails to explain why his gods qualify for this status as “real, literal beings” and comic book characters do not. I agree that religion matters in a way that fan fiction does not, but, as Anomalous acknowledges, the line between the two is pretty blurry.

Another good example of the poly-recon group is Dionysian Sannion, who argues in a post entitled, “Making Light of Superhero Worship”, that there is a difference between make-believe and reality and that the heroes and gods belong to the latter. About the gods he says: “These beings have an existence independent of our own — unlike fictional characters they are not products of our minds.”

Sannion perpetuates Krasskova’s error about the historicity of heroes: “True hero worship involves honoring the person for who they were and what they did — not for the idealized version we wish they were.” This argument ignores the gap between historical sources and historical reality. And what about the gods? While some of them may have been human at one time (according to the myths), most of them are cosmic or born from cosmic gods. In other words, most of the gods were never historical; they were always mythical. And if that is the case, then how do they differ from comic book heroes?

Another concern I have with reconstructionist argument is the apparent double standard. I have heard many polytheistic reconstructionists express outrage at the suggestion that their gods are, in some sense, not “real”, and yet many of these same individuals are very ready to tell other polytheists that their gods are not “real” enough. A good example of this is Sarenth argues that “Superheroes Are not Worthy of Worship” and then attempts to “Dialogue with Pop Culture Pagans”.

Setting aside the issue of the historicity of the heroes and gods, I think that Krasskova does make an important point in her post about the trivializing effect of divinizing superheroes:

“… religion is not entertainment. The point of veneration be it of the Gods, ancestors, or cultic heroes is not one’s personal entertainment. Conflating comic book heroes with ancestral heroes is not a question of orthodoxy vs. modern avante guard perspective, but of singular comprehension of the role of cultus in one’s religion vs. spiritual puerility.”

Our culture has a tendency to take everything holy and transform it into vapid entertainment. And I suspect that Krasskova is on to something when she identifies the conflation superheroes and heroes as another manifestation of the modern descralizing of our lives. I think this concern may account for much of what is driving the reconstructionist angst over so-called pop culture Paganism. The attitude of devotion which characterizes polytheistic religiosity seems to be missing from more Self-centric and earth-centric form of Paganism. (I have written before about introducing devotional practice, true worship, to non-theistic Paganism here.) But the problem is this: how do we distinguish “religion vs. spiritual puerility”? One person’s worship of Superman might be true religion, while another person’s adoration of Odin might be an example of what Kasskova calls “puerility”. And I don’t think this judgment based on the historicity of the object of the devotion.

Non-reconstructionist deity-centered polytheists

While resembling reconstructionists in terms of their understanding of the gods and their relationship to them, non-reconstructionist polytheists differ from the former in that their gods may not derive from historical sources. Instead, they arise from other sources, like interaction with the natural environment, as in the case of worship of fairies or land spirits. Or they may arise from interaction with myth, but transformed into new gods. Like reconstructionists, these polytheists are also often reluctant to speculate about the ontological nature of the gods (or spirits etc.). And like reconstructionists, what matters to them is their relationship with these beings, not their beliefs about them. They speak in terms of faith and hubris, terms which until recently were absent from Pagan discussions. Where non-recon polys differ is that they don’t have recourse to historical sources to legitimize their worship. And if one is not bound to historical deities, then the question of what distinguishes the worship of one’s deities from the adoration of comic book characters becomes even more acute.

A good example of a non-reconstructionist polytheist is Aine who worships new gods, spirits, and fairies. For Aine, the gods are not archetypes, as he explains in his self-described “rant”:

“These gods and spirits are real to me. In the religion, they are treated as real entities deserving of offerings and rituals, rituals that are more focused on the gods and spirits than on our internal mindscapes.”

Aine goes on to express his frustration with the “atheist-pagans” who either want to explain his belief in terms of archetypes or who want him to explain his belief to them in a way they can accept. But, interestingly, Aine doesn’t deny the validity of those atheist-pagans’ practice: “My having faith and fostering a path that has faith as a core component doesn’t mean people are suddenly unable to have archetypal spiritualities.” On the other hand, while Aine believes his gods are “real” (i.e., more than psychological), he is not entirely sympathetic with the reconstructionist criticism of comic book character veneration, as he explains in another post, here, since it would seem to exclude new theophanies like his own.

Aine also makes an important point that, even though one is worshiping new gods, discernment is still important:

“There’s also this silly idea that gets brought up that somehow if you believe in gods and spirits you must believe in them without any doubt or discernment. Again, no. Belief doesn’t cancel out thought, as much as some people might claim it does. I’m scared of where I would be if I didn’t take a moment to just think and consider and doubt. […]

The issue of discernment is also taken up in a characteristically nuanced fashion by the prolific P. Sufenas Virius Lupus, in “My Writings on the Tetrad Group Are no Fanfic”. PSVL is one of the founding members of the Ekklesía Antínoou–a queer, Graeco-Roman-Egyptian syncretist reconstructionist polytheist group dedicated to Antinous, the deified lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. The Tetrad, not incidentally, are “four transgender or gender-variant deities, who have come into being in our time as divine figures whose living myth reflects the realities of twenty-first century gender diversity.” PSVL writes:

“There is a sense among many pagans of all stripes that every aspect of life can be sacred, can be service to the gods, can be filled with holiness, and therefore it should be. There is nothing wrong with that at all, and I agree fully with that aspiration; but, it is mostly an aspiration and not a reality for most of us. The mistake comes when it is automatically assumed that because any aspect of life can be sacred, that therefore it already is just by sort of saying so in a blanket fashion, and realizing it is such in one’s own mind. In my experience, that doesn’t work, and hasn’t always worked.

“… just because someone likes something, and can find a connection between it and spiritual practice or potential cultus, doesn’t mean there automatically is one. …

“I do think there’s a horrible potential for error, though, when people begin to mistake these activities for spiritual practice, or to take the engagement of active and creative imagination in them for the same process which often goes into devotional or cultic activities. Both actively engage the imagination and creativity, as I’ve said repeatedly (and perhaps unhelpfully!) here; but, there is a difference, and it is the cultic factor mentioned above.”

(emphasis added).

I agree with PSVL 100% on the pansacramentalism issue: just because something may be sacred does not mean it necessarily is. But then PSVL tries to draw the distinction based on whether there is “cultic activity”, and it is unclear what qualifies as “cultic activity”. PSVL then attempts to draw a line between fiction and myth that I don’t think is as sharp a distinction as e hopes:

“I would make the following broad distinction between the two: ‘fiction’ is something that is neither factual nor True, whereas “myth” is never factual but always True. No matter how much someone likes the story, nor ‘believes’ in it, Don Quixote never tilted at windmills, Natty Bumppo never had adventures with the last members of the Mohican tribe, and Tony Stark never made forty-two Iron Man suits. Sure, we can take lessons from these stories, and they can even go on to inspire our lives or shape them in some fashion or other, but they’re not True in the way that all actual myths are True. Achilleus never helped to attack Troy; Jason never voyaged with the Argonauts, and Perseus never cut off Medusa’s head…at least factually speaking; but, all of these things are mythic, and as a result there is a Truth to them that transcends their time and place of writing and telling, and why they are still relevant to us today, and can touch our lives and change them profoundly under the right circumstances. It’s why cultus to some of these figures occurred in the past, and is occurring again today.”

The fact is that the line that PSVL draws between Achilles and Don Quixote is arbitrary. The former is mythical to PSVL, while the latter is not to PSVL; but that’s just PSVL. For another person, the reverse may be true. There is no principled basis for drawing an absolute distinction between the two. In the end, PSVL makes the same error as the recons, by privileging old sources over the new.

Self-Centric Magickal Pagans

These are Pagans whose beliefs are influenced by ceremonial magic or chaos magic. The may be polytheistic in a “soft sense”, but are often more monistic. This group also differs from the first two in that they are willing to theorize about the nature of the gods. They see the gods as “thoughtforms” or egregores, by which they mean that they are creations of our mind, but they take on a life of their own and exist semi-independently. This group is largely responsible for the idea that characters from pop culture can take on a life of their own and begin to act like gods.

Back in January, before the debate started, Gus diZerega wrote 3-part series on pop culture and the formation of independently acting thought forms in “Dark Vader, Luke Skywalker and Thought Forms”, “Thought Forms and the American Crisis: Esoteric Insights”, and “If Thought Forms Exist, What Can We Do About Them?”. DiZerega writes:

“Making a thought form is an act of magick. It is kept potent to the degree it is ‘fed’ with the energy of strong focused attention. An unintended thought-form is in keeping with the same model of how the mental world works, but it is independent of any particular person’s will and attention. If such a collective creation is possible, human beings can unintentionally create formations of mental energy to some degree both independent of them and able reciprocally to influence others.”

DiZerega goes on to tell the story of “Lark” who could commune with Darth Vader!

In case you were wondering whether anybody really is worship superheroes or whether this is all academic, here’s a response from someone on “Why Pagans Can Be Worse than Fundamentalists” who explains that Batman is real, just like all the other gods. This was posted on a site called “Sons of the Batman” which is described as “a magical order dedicated to the spiritual model provided by the world’s greatest urban shaman: The Batman.”

Another example of the Magickal Pagan is Taylor Ellwood, who wrote “In Defense of Pop Culture Magic” and actually has written a book on the topic. He defends “working with” fictional characters and alludes to the results of her own “16 plus year relationship with Thiede, a ‘fictional’ character”. Ellwood writes:

“I’ve had interactions with pop culture entities that are and have been meaningful and aren’t mere flights of fancy or fantasy. I consider the pop culture entities I work to be real entities by virtue of the relationships that I’ve developed with them.”

I think it is noteworthy that Ellwood writes in terms of “magic” and “working with” fictional beings, rather than religion and worshiping these beings, a distinction which Julian Betkowski highlights in his post, “The Need to Understand the Role of Religion”. Betkowski writes that the the origin of pop culture Paganism to be Chaos Magic. I agree that magic(k) is distinguishable from religion. There is a difference between the using of the gods, like they were batteries, and the worship of the gods, like they were … well, gods.

Similarly, Sorcerer, Jason Miller, writes in his post, “Fictional Characters, Gods, and Spirits”, that the concerns of Pagans are different from the concerns of magicians. “Magicians,” he says, “are largely just concerned with results,” while Pagans are “concerned with defining their religious movement and having that movement taken seriously on the world stage.” While I agree that the potential for embarrassment is a factor in this debate, what I think Miller doesn’t really get is that the concern of many polytheists is the lack of piety or reverence, which seems absent from the utilitarian discussions of magickal “use” of gods or “god-forms”.

I think Magickal Pagans are to be credited for at least attempting to offer a theory about the ontological nature of the gods, one that is not reductive and does not psychologize the gods, thus preserving to some degree their “otherness”. On the other hand, there is a danger when the gods are invoked in practical magic that they will become mere tools, playthings of magicians. And I think something very important is lost when this happens. (This has been a concern of theurgists since the time of Imablichus at the turn of the 4th century CE. An interesting debate occurred between Neoplatonists Porphyry and Iamblichus regarding whether magic was intended to draw the gods into men or to elevate men to the gods.)

As the Chaos Witch, Lee, explains, it is easy to “see why people might find it offensive that their faith will get diluted into a series of interchangeable symbols in soft eclectic blasphemy.” On the other hand, the line between fandom adoration and religious worship can be pretty thin:

“What is the difference between a legitimate adoption of a paradigm for serious worship and totally denigrating the paradigm in which you choose to dip your toes in simply because you are only approaching it by the means of ‘paradigm adoption’ on the first place?”

Self-Centric Archetypal Pagans

These are the more Self-centric Pagans (note capital “S” used to distinguish the Self from the ego) who see the gods as “archetypes”, products of our minds, powerful in their influence over us, but not existing independently of us. This group interprets the experiences of the other groups above in psychological terms. In doing so, they may insult those who find such explanations to be reductive.

An example may be Sunweaver post, “Making Light: Hero Worship”, which set off this controversy. (As noted above, although she approaches heroes as archetypes in her post, Sunweaver herself experiences the gods as objectively existing entities with distinctive personalities.) In her post, she compares contemporary superheroes to ancient Hellenic heroes:

“Our Homer is not any of the prose authors raised upon pedestals by many an English teacher, but the quirky white-haired Stan Lee. Our clever Odysseus, once clad in bronze armor, now bears the name Tony Stark and if he has a house in Ithaca, it’s in New York. The Hulk is our Ajax. Achilles is now… Cyclops? And then there is James Tiberius Kirk, another Odysseus, perhaps, a hero with his wayward crew on a journey to seek out new life and new civilizations, boldly going where no man has gone before!

“… giving your spiritual props to a historical person doesn’t mean you can’t also worship the ideals of patriotism, integrity, justice, and bravery that we embody in our superheroes. And they are no more or less real than the figures from Homer and Hesiod.“

(emphasis added).

This is not a new idea. It can be traced back to Joseph Campbell, who Sunweaver invokes in her follow-up post, “Making Light: Help me, Joe Campbell, you’re my only hope”:

“So, where I see interesting embodiments of archetypes that often follow similar journeys as the old heroes and who bring ideas about both virtue and vice to a modern audience, others see ‘just’ stories. Where others see the old heroes as historical persons worthy of veneration, I’m simultaneously skeptical of their historicity while accepting their importance in a Hellenic context. I just take a more metaphorical approach.”

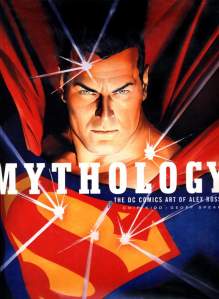

More recently, the idea that superheroes are modern gods been written about by Grant Morrison in Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human and Christopher Knowles in Our Gods Wear Spandex: The Secret History of Comic Book Heroes. Also check out Ben Saunders’ Do The Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy, and Superheroes and Don LoCicero’s Superheroes and Gods: A Comparative Study from Babylonia to Batman.

Another example of an Archetypal Pagan is an unidentified person whose exchange with The Anomalous Thracian was was reported in the latter’s “rant”, “My Gods are Not Archetypes”. The unnamed person explains how they see the gods in typical archetypal fashion:

“I believe that the pantheons of Goddesses and Gods are, in fact, archetypes. Archetypes that represent different aspects of ‘The One’ are inherent in the human psyche and found in all cultures throughout history. I would argue that all religious literature, or ‘mythology’ is fictionalization utilized to demonstrate a human perspective/perception of the multi-faceted Divine. The archetype behind many ‘super heroes” is the same as that found in the depiction of many Gods or Goddesses.”

I appreciate the concern of polytheists that archetypal accounts of the gods are reductive. Indeed, I agree that many such archetypal explanations are reductive, especially when they reduce the gods to mere metaphors. Such descriptions fail to account for the experience of the “otherness” of the gods, which seems to be precisely the experience which compels polytheists to insist on the “real-ness” of their gods in contrast to “mere archetypes”.

However, Jung’s concept of the archetype was more nuanced than such accounts suggest. This is a subject that I have written about numerous times. Check out my post at Humanistic Paganism entitled “The archetypes are gods: Re-godding the archetypes” and my posts here, “Are the gods real?” and “What is it that rules outside man’s self?: the gods as ‘other'”. Jung, for example, writes that the ruling powers of the psyche “function exactly like an Olympus full of deities who want to be propitiated, served, feared and worshipped” and compel “the same belief or fear, submission or devotion which a God would demand from [humankind].” Seen in this way, the archetypes are so much more than “mere metaphors”.

Non-theistic Earth-centric Pagans

For this group, their Paganism has little to nothing to do with gods. Very few people from this group seem to have weighed in on this debate. This group sees all this god-talk as distracting from what really matters, interacting within the natural environment. They see gods as anthropomorphisms which are unnecessary at best and destructive at worst.

Christine Hoff Kraemer‘s response, in “Notes Toward a Pagan Theology of Fiction”, might fall into this category (although she too describes herself as a variety of polytheist). She writes that she wonders whether fiction (and hence, pop culture Paganism) can distract us from spiritual practice:

“As someone who makes her living largely at a computer screen, I know I already struggle to be present with my little square of earth and its particular flora and fauna (including the human fauna who are my neighbors). […] I worry that fiction can have an escapist quality, and that engaging with it too directly in my spiritual life might distract me even further from the local.”

Conclusion

To sum up, I think the recons have a legitimate concern about so-called pop culture Paganism. It has the potential to desacralize Pagan religiosity. However, none of the attempts that I have seen by recons to distinguish true worship from profane fandom have been logically compelling. Aine writes about exercising “discernment”, a term that I see used increasingly among polytheists. The question is whether there are any guidelines that we can rely on when trying to discern true worship. That will be the subject of my next post.