This essay ran originally in the August 29, 2020 edition of the Sedalia Democrat. It is perennially relevant and has become relevant again with the onset of devastating flash flooding in Southwest Louisiana this week.

Why don’t they just move?

It’s a question I see after every major hurricane, including this week’s Category 4 Hurricane Laura, which battered the Louisiana coast.

Why would you live in an area where your property or even your life could be destroyed by a massive storm surge? Why does the government allow people to rebuild there? Why can’t we just move people further inland, to higher ground, where it’s safer? Isn’t it foolish to live where the wind and the waves are constantly trying to kill you?

And I remember.

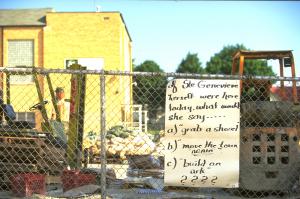

I was just shy of kindergarten when the Great Flood of 1993 wreaked havoc on my riverside community. The memories still stand out brightly. It was June, maybe early July. We were driving to swimming lessons in the county seat. As we neared the public pool, we could see that the Illinois River had begun running over the road, roughly 350 feet out of its banks. My friend’s mother inched forward in her full-size van as the quick brown water swept across the pavement. We crawled along for a moment, then backed up, turned, and went home. It was my last look at that town for months. A few weeks later, the local levee would break, flooding 11,000 acres of land on both sides of the river and inundating homes and businesses. The river would later crest at an historic 42 feet. Full recession of the flood would not be complete until November.

I remember sandbags and tetanus shots. White aluminum cans of “emergency water” from Anheuser Busch. T-shirt fundraisers. National Guardsmen. Riverside houses that looked like they’d been bombed out, painted with colorful murals to hide the emptiness. Teachers who boated in to work. Trips to get groceries that took hours and hours. Laments and rocks hurled at the water’s edge. And a feeling, even at my young age, of being pinned, trapped in our little corner of the world between the wicked Illinois River and the mighty Mississippi.

Major floods had happened on the Illinois and Mississippi many times before, including 1965, 1973, and 1979. Minor flooding was so commonplace as to be almost boring. And major floods would happen again: 1995, 2008, 2015, 2017. But the Great Flood of 1993 was called a “500-year flood event.” It was not likely, experts said, that such a disaster would ever happen again in even our grandchildren’s lifetimes. But, in 2019, just a quarter-century later, the unthinkable happened again. The same broken levee, the same disastrous results. A river crest just two feet below “historic.”

“They should just leave.”

Gosh. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard it.

“There’s not that many people living there anyway. Turn it into a nature preserve.”

“The government should force them out.”

“How stupid can you get?”

“It’s time to talk about the wisdom of living near the river.”

Always said with the air of someone who knows it all. But what they don’t know, these who don’t live where hurricanes or floods or earthquakes or volcanoes threaten, is this:

“This is my home.”

This is my home. My parents’ home. My grandparents’ home. My great-great grandparents’ home. This is land our families have loved and lived on for almost 200 years. A place we’ve farmed and fought for over decades as the waters advance and recede around us. This is where we were born, and where we will be buried. It is part of us, and the blood that runs in our veins is mingled with the Mississippi.

Or the Gulf.

Or the lava flow.

Or the driving snow on the side of the mountain.

We can be prudent. We can regulate construction on the flood plain. Or build stronger buildings and storm shelters. We can buy insurance. We can plan, and develop wisely, and use all of our human wiles and technologies to pin down Mother Nature. But we can never box her in, no matter where we live. Always, sometimes, the environment will try to rise up and try to kill us. There is no such thing as perfect safety. We all live in a tension between love and danger, and when we find the spot where the love overcomes the danger, we call it home. That is no small thing.

That is why we don’t “just move.” No matter where we are, no matter what threatens.