Tis the season to honor the dead. As a heathen and mortician, this has always been my favorite time of year. However, it has recently become one of the most emotionally complex seasons for me. My story isn’t anything special or unique. In fact, it’s so common, this tale of abuse and estrangement and suicide, that there really isn’t anything remarkable about it. This is why it’s important to recognize such a tale: no matter what you endure, you’re not the only one, and there’s nothing wrong with you if you’re unable to celebrate like other pagans and heathens.

In mortuary school, we spent a semester studying the types of grief and how to support people through the bereavement process. Like most of the program, the course was very heavily slanted towards the Christian philosophy, taught by a very devout Christian psychologist. I happen to be one of those lucky bastards who has never once gotten pushback for being heathen in my nearly 40 years of roaming the earth. Since I was raised heathen, it’s always been part and parcel of who I am. The older I get, the more obnoxious I am when it comes to being loudly “out” about it. So the bereavement professor didn’t debate me when I countered his Christian counseling advice with heathen/”other” points of view. He was really quite fascinated by my beliefs and experiences, even if he thought I was the weirdest student of his career (which, given that he dealt with a lot of mortuary students, is saying something). However engaging I found his class, though, it didn’t really prepare me for my own experience with bereavement years later.

When Grief Gets Complicated

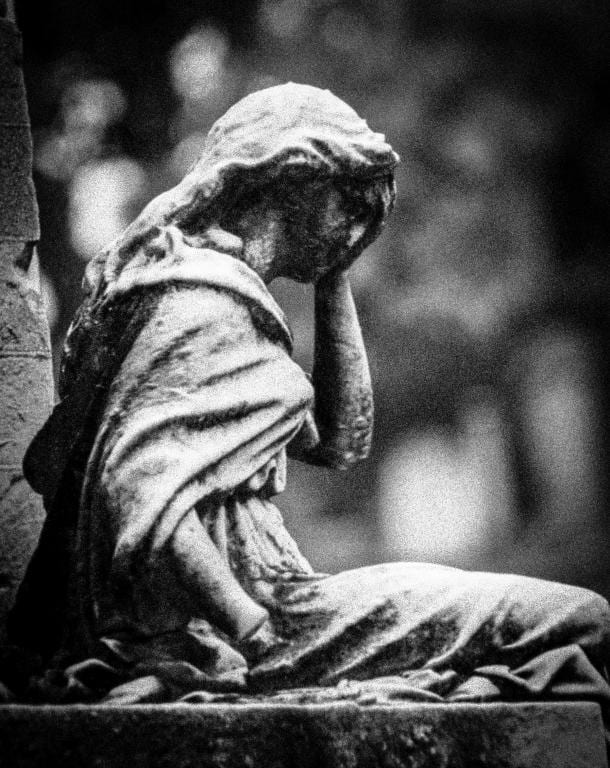

Ironically, when you love someone, bereavement is fairly straightforward: you grieve because you love them, and you miss them, and your life is profoundly altered by their absence. You know that if there’s a funeral, you’ll attend. You know you’ll be distraught in the coming days, weeks, months. Your friends and family understand this and support you as you process your emotion and figure out your new normal. Birthdays and anniversaries will hurt, but you’ll have fond memories to fall back on. If you’re heathen or pagan, they’ll become part of your ancestor altar, and you’ll speak proudly of them in ritual, make offerings to them, have that time in quiet contemplation reflecting on them as you share a drink at the altar.

It gets messy and confusing when your relationship with the deceased isn’t so simple. When my estranged father died unexpectedly a few years ago, I had no idea how to respond. We hadn’t spoken in almost 15 years. It was mutual estrangement, fear on my end and fury on his. In fact, one of my greatest fears throughout adulthood was that he would die and I’d never know it: I’m his only child, and the only grandchild in his family. My surviving aunt and uncle are also estranged, from me and from each other (I’m really painting a warm and cozy family portrait here, no?). Most of my life has been spent in fear of my father figuring out where I lived and showing up to finish what he’d attempted ages ago. That’s why I worried about never learning of a possible death: without knowing, how could I ever know that I was safe once and for all?

That was the first phase of the complicated bereavement I experienced when I received the news that he’d died at the end of October, just a few days before his birthday: relief. I was stunned, but overwhelmingly relieved to know that his literal reign of terror was over. That relief was short-lived as my mom and I simultaneously realized that, given the nature of his death, we weren’t yet in the clear. What if he’d mailed something? He didn’t know where I lived, but he still had my mother’s address. She immediately called my stepdad to warn him not to open any packages that might come from him. We spent the next few weeks stressed and anxious, worrying about receiving one final strike from him.

The anniversary of his death was just a few days ago as of this writing, and all I could think about was the fear we felt about receiving one last vindictive blow. Thankfully, the only thing the mail brought was his final will, in which I was firmly and officially disinherited. Once again, pure relief: Mom and I were safe, and I didn’t have to worry about owing any kind of gratitude or spiritual debt to him.

Relief and fear were followed the next day by an extraordinary emotional breakdown, and the grief truly became complex. I was fine, until I wasn’t. Without any sort of warning tremor, I burst into hysterical sobs, the kind that wrack the entire body and drain the soul to nothingness. I was confused as I wept. As callous as it sounds, I wasn’t sad he was dead. So why the raw grief?

I wasn’t mourning him. I was mourning who he should have been. I was grieving the knowledge that he would never apologize for what he did to me and to my mom. I was crying from the pain that he would never be the dad he was supposed to be. And following the sorrow was anger. I was furious at him for making the choices he did. Livid about the the things he did, the callousness with which he did them, and the inability (or refusal) to understand why Mom and I literally fled his wrath.

It’s perfectly normal and healthy to feel anger at the dead. It’s so natural it’s actually one of Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief, which we covered extensively in our bereavement course in mortuary school. Responding to death is a messy affair. The more complicated the relationship with the deceased, the more complicated the onslaught of emotions will be. It’s okay to cry for someone who was cruel, it’s okay to feel anger towards someone who died, and it’s okay to feel relief. The prime take-away is that you allow yourself to feel these emotions and move through them; don’t get hung up on one and wallow indefinitely. Give yourself permission to experience whatever it is you’re feeling, and then work through them to help you into your new reality.

It’s Okay to Skip the Funeral

I didn’t attend the funeral. It wasn’t even a question about whether or not I would. He lived hundreds of miles away, we hadn’t spoken in well over a decade, and the chances were exceedingly high that no one in attendance would have even known he even had a biological daughter. Besides, I didn’t want to subject myself to the typical platitudes of “he was a good man,” because that would have been deeply insulting and hurtful to me and my mom. Maybe he was a good man to some folks. Not to us, he wasn’t. Grief can complicate itself further if you learn that the person who was so violent towards you was kind to other people. Makes you wonder what was wrong with you to deserve the abuse. Rationally, you know you didn’t deserve the torture and the pain. Doesn’t mean you won’t wonder why you weren’t good enough to that person.

It’s important to understand that you should never be forced into attending a funeral just for appearance’s sake. It’s an event meant to offer comfort and social and spiritual support to the bereaved. If your relationship with the deceased was toxic, then attending a service and hearing about how wonderful so-and-so was can be harmful to your well-being. The decision to attend public mourning rituals should be entirely up to you and your ability to cope with stressful memories and negative emotions.

That said, it’s immensely helpful to have your own memorial service to say goodbye as you see fit. After all, funerals are important because they mark indelible shifts in the lives of the survivors. Death shouldn’t pass by unremarked, it’s too big an event, and it will still have a personal impact even if the deceased was no longer a part of your life. There needs to be a chance to make some kind of peace with the situation, to shift and adjust to the new reality. My father was heathen, just as his father was heathen, and I felt the gentle obligation to mark his death as heathens do. So the night I got the news, I said my goodbye in the heathen way, calling the gods to witness my words and the libation I offered: a can of Last Chance IPA.

I said what I needed to say, and Odhinn, Thorr, and dear Loki were with me, listening, weighing my words and giving me strength. I did my duty as a daughter, whether he deserved it or not. I am his only child, so the responsibility was mine alone. It needed to be done, and I did it. It was the final moment before cutting the ties once and for all. The little funeral blót I did marked the transition from dealing with trauma to being free of him forever.

Yes, I had a lot of conflicting emotions to work through in the following days and weeks, but those emotions weren’t really about him. They were about me peeking my head out of hiding and being reborn into a world where I didn’t have to worry about him ever hurting me again. Death is cyclical: we all know that when one life ends, a new one begins. Birth and rebirth are just as big and scary and painful as death. You just have to let yourself experience the emotional flood so you can move forward with limited baggage. Denial never did anyone any good.

What Then of Celebrating the Dead?

Samhain, Halloween, All Souls: whatever you celebrate this time of year, it can get dicey for those of us who have lost people that were never the people they could have been. As a heathen, the only holidays I really celebrate are Yule and Midsummer. As a gothy type (though as I age, my fashion sense shifts ever further from Victorian Goth to Pragmatic Ennui) and a mortician, I enjoy holidays that honor the dead. My friendship with Mortellus, of A Crow and the Dead fame, has sparked more of an active interest in the witchier side of things. My heathenry has always been the practical sort, simply infused in how I go about my day and how I interact with people, with a sometimes maddening dose of gods flicking my ear and tugging at my hair. I’ve always had an interest in the more woo things such as seiðr, and Mortellus has graciously offered to help me learn a bit o’ necromancy. Primarily, they’re helping me learn how to protect myself from the unwelcome dead when I journey to Hel’s halls in search of ancestors I hold dear.

Even though the ties have been cut legally, physically, and spiritually, I still don’t trust opening myself up to communing with the dead without those protections. It isn’t demons or malicious entities I fear: it’s my own father. And, to be honest, his mother, who taught him the ways of torment and cruelty. In life, they were both so vindictive and spiteful that I’m sure they’d latch on if I poked my head through the veil separating our worlds. I don’t believe they can hurt me, thanks to the reassurance from my fiercely protective fulltrui. I just don’t care to hear anything they have to say. I have no interest anymore, and I don’t want them interrupting and badgering my happy reunion with my beloved dead they way they did in life.

It’s a real enough concern that it scared me away from a Zoom workshop Mortellus had about seances. I was excited for it until I realized it was happening on the anniversary of my father’s death. I trust Mortellus’s abilities as a BTW and Necromantix to keep him quiet, but figured they didn’t need to worry about any kind of interference from him. Wouldn’t have been enjoyable for anyone else attending the virtual workshop, either.

These days, when the air and leaves turn crisp and the humming of departed souls reverberates in our hearts, I tread carefully. I do have dearly departed souls I honor and cherish, and I know at least one of them is a protector. I know that when I’m ready to blur the lines between this world and theirs, my grandfather will keep me safe. These things aren’t to be rushed, however. Though I’ve cut the ties between us and have moved forward with my shiny new out-in-the-open life, I can’t afford to be foolish and go traipsing around the realm of the dead just yet.

I’m wistful for when Halloween brought excitement instead of reminiscing about my father. It’s almost a final act of spite on his part, planning his death for the cusp of Halloween. So I lie low throughout October, evading the streams of Samhain related revelry. It’s only been two years since he died, and soon enough I’ll be able to disassociate his Death Day with the Halloween season. It won’t be long before I’m able to delve into Samhain celebrations with my pagan friends. Until then, I’m not comfortable dancing along the edge of the veil. That’s okay.

You might not be willing to put yourself out there this time of year, either. That’s okay, too. Don’t be discouraged by everyone else’s celebrations and eagerness to honor those who’ve crossed. Take time for yourself, work through the scads of heavy emotions that come along with complicated bereavement, and take heart that like all things, this too shall pass.