“Sad experience proves that human authority fails where religion is set aside.”

– Pope Benedict XV

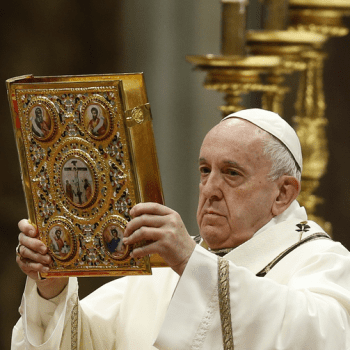

On Sunday, July 27th, Pope Francis spoke briefly after his Angelus address about the one hundred year anniversary of the beginning of World War I. Here is what he had to say:

“Tomorrow marks the one hundredth anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, which caused millions of deaths and immense destruction. This conflict, which Pope Benedict XV called a ‘senseless slaughter’, resulted, after four long years, in a most fragile peace. Tomorrow, as we remember this tragic event, I hope that the mistakes of the past won’t be repeated, but that the lessons of history be taken into account, that the demands of peace through patient and courageous dialogue are always made to prevail…

Brothers and sisters, no more war! No more war! Above all, I think of the children, those who have been denied hope of a decent life, of a future: dead children, wounded children, maimed children, orphaned children, children who have remnants of war as toys, children who don’t know how to smile. Please stop! I ask you with all my heart, it’s time to stop! Stop, please!”

Furthermore, foreign policy analyst Fareed Zakaria recently wrote a deflating essay on “The Rise of Putinism” where governments are looking away from liberal democracy to authoritarian states for insights on successful leadership. As Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban would explain,

“The most popular topic in thinking today is trying to understand how systems that are not Western, not liberal, not liberal democracies and perhaps not even democracies can nevertheless make their nations successful.”

With Pope Francis’ entreaties and Fareed Zakaria’s analysis in mind, I began considering the value of what another Pope had to say about World War I. Namely, Pope Benedict XV (take note – the 15th, not the 16th). But before we do, a little background is in order…

It all began so easily. On June 28, 1914, Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip found himself on a street in Sarajevo within firing distance of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. And he pulled the trigger. What would ensue thereafter was massive and inexplicable. Europe would be consumed with diplomatic posturing, declarations of war, invasions, and counterattacks filled with bayoneted rifles, tanks and poison gas. The Great War, it was dubbed. The War to End All Wars, it was called. Germany, Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, France, Great Britain, the United States (among others) vied for bloody supremacy. And it was winner take all.

Within weeks of the beginning of the First World War, Pope Pius X would die and Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista Della Chiesa would be chosen to succeed him. He would adopt the name Pope Benedict XV after St. Benedict, the Christ-centered founder of monasticism. But his accession to the Chair of St. Peter would be obscured by Europe’s unrelenting and ruthless bloodshed. On November 1, 1914, three months into the war, the Pope released his first encyclical Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum (Appealing for Peace) addressing the carnage of the war. Here is what Pope Benedict XV had to say

about the ruthless irony of the war:

“The combatants are the greatest and wealthiest nations of the earth; what wonder, then, if, well provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised, they strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror… Who would imagine as we see them thus filled with hatred of one another, that they are all of one common stock, all of the same nature, all members of the same human society? Who would recognize brothers, whose Father is in Heaven?”

about the absence of earnest reconciliation:

“Surely there are other ways and means whereby violated rights can be rectified. Let them be tried honestly and with good will, and let arms meanwhile be laid aside.”

about the danger of morally rudderless states:

“Ever since the precepts and practices of Christian wisdom ceased to be observed in the ruling of states, it followed that, as they contained the peace and stability of institutions, the very foundations of states necessarily began to be shaken. Such, moreover, has been the change in the ideas and the morals of men, that unless God comes soon to our help, the end of civilization would seem to be at hand.”

about the hypocrisy of the “language and philanthropic institutions of peace”:

“Far different from this is the behaviour of men today. Never perhaps was there more talking about the brotherhood of men than there is today; in fact, men do not hesitate to proclaim that striving after brotherhood is one of the greatest gifts of modern civilization, ignoring the teaching of the Gospel, and setting aside the work of Christ and of His Church. But in reality never was there less brotherly activity amongst men than at the present moment.”

“Noble, indeed, and praiseworthy are the manifold philanthropic institutions of our day: but it is when they contribute to stimulate true love of God and of our neighbours in the hearts of men, that they are found to confer a lasting advantage; if they do not do so, they are of no real value, for “he that loveth not, abideth in death.” (I John iii. 14)

about the creeping ideologies promising heaven on earth:

“Once the plastic minds of children have been moulded by godless schools, and the ideas of the inexperienced masses have been formed by a bad daily or periodical press, and when by means of all the other influences which direct public opinion, there has been instilled into the minds of men that most pernicious error that man must not hope for a state of eternal happiness; but that it is here, here below, that he is to be happy in the enjoyment of wealth and honour and pleasure: what wonder that those men whose very nature was made for happiness should with all the energy which impels them to seek that very good, break down whatever delays or impedes their obtaining it.”

and the temptation to jettison the wisdom of tradition for the empty promises of the new:

“Infatuated and carried away by a lofty idea of the human intellect, by which God’s good gift has certainly made incredible progress in the study of nature, confident in their own judgment, and contemptuous of the authority of the Church, [those infatuated with the Modern world] have reached such a degree of rashness as not to hesitate to measure by the standard of their own mind even the hidden things of God and all that God has revealed to men…Those who are infected by that spirit develop a keen dislike for all that savours of antiquity and become eager searchers after novelties in everything.”

In spite of the Pope’s repeated prayers and entreaties, man would have his way. And the war would march on for four long bloody years. The legacy of World War I is 37 million dead, the fall of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires and the rise of Communism and Fascism.

And as we hear what Pope Francis said, consider what Fareed Zakaria warns about and read what Pope Benedict XV wrote, we are confronted with a very unsettling question:

Has anything changed in one hundred years?

Well, no. Man’s appetites are still selfish and insatiable. Wicked movements change in name and locale, but remain wicked. Technology still serves to annihilate, only on an ever-greater scale.

But, in the midst of this depressing testimony to man’s enduring inhumanity to man, do you know what else doesn’t change?

The Truth.

The dignity of man no matter how fallen, the calling to something greater than ourselves, the redemption that is ours for the taking and the eternal bliss that awaits us in heaven. It is a narrative of man (and woman) that transcends the muck of the trenches, the stench of infection and the bitter anguish of suffering and death. This is embodied in our kinship with Christ. And that Truth will never change. Not in a hundred years. Not ever.

Pope Benedict XV would end his encyclical with a prayer and work tirelessly for humanitarian ends until he died in 1922. His concluding prayer follows.

“May He who said of himself: ‘I am the Lord…I make peace’ appeased by our prayers, quickly still the storm in which civil society and religious society are being tossed; and may the Blessed Virgin, who brought forth ‘the Prince of Peace,’ be propitious towards us; and may she take under her maternal care and protection Our own humble person, Our Pontificate, the Church and the souls of all men, redeemed by the divine blood of her Son.”

May God rest the souls of those who suffered and died in the Great War. And may He guide us to follow His light in our uncertain way ahead.

Amen.