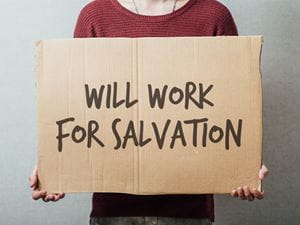

The Roman Catholic Church’s understanding of the role of works in salvation differs from that of most Protestants. Both traditions agree on the crucial role of grace. That is, salvation itself wouldn’t even be possible were it not for the foundational love of God and desire to redeem the world; this love toward us was made visible in Jesus Christ, whose life and death made salvation possible. Grace is essential, and nothing can be done to make God owe us that grace.

What do Catholics believe about salvation?

At this point, though, Protestants and Catholics begin to see things differently. Protestants teach that the grace of God, effective in life through conversion and faith, fully justifies the sinner before God. The sinner is made completely right with God and eternal life is assured. That new relationship then begins to change the sinner, a process called sanctification, and good works are the sign of that transforming power. Catholics, on the other hand, teach that sinners, reconciled to God by faith, now must respond from their own free will, cooperating with the process of justification through good works. These good works have effective power to attain merit before God and, ultimately, eternal life.

Protestants adhere to the formula “justification by faith alone.” They argue that the Catholic model of Christian life is synergistic—that is, that it affords too much weight to human achievement. They teach that it is God alone who saves, God alone who makes good works possible, and God alone who grants eternal life in the end. Catholics prefer to focus on the human component: “Moved by the Holy Spirit, we can merit for ourselves and for others all the graces needed to attain eternal life, as well as necessary temporal goods.” (The Catechism of the Catholic Church)

The Protestant argument was developed during the Reformation and the Catholic response was codified in the Council of Trent (1545-1563), but since that time Protestants and Catholics have had several formal conversations around this issue. Most recently, the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation issued a Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (1999) in which they attempted to resolve some of the misunderstandings around this issue and recognize that the two perspectives are mutually exclusive. It affirms that "Together we confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ's saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works."

The Declaration was adopted by the World Methodist Council in 2006, and by the World Communion of Reformed Churches in 2017. Despite these commendations, the Declaration has been disputed by some members on every side. Some Catholics believe that the Declaration betrays the authoritative word of the Council of Trent, which asserts that “life eternal is to be proposed to those working well unto the end, and hoping in God, both as a grace mercifully promised to the sons of God through Jesus Christ, and as a reward which is according to the promise of God Himself, to be faithfully rendered to their good works and merits.” Some Protestants also object, feeling that the Declaration makes void the Protestant recovery of the true gospel, i.e., salvation by faith alone.

Read more about the Reformation split between Protestants and Catholics here.

12/8/2021 3:41:17 PM