Those who believe they are being pushed out, marginalized and endure extreme suffering for their Christian faith may be tempted to retreat in the face of the apparent threat. We can fall back on the comfort of nostalgia bound up with memories of a national Christian heritage and election claims like “Make America Great Again” (Donald Trump, 2016) or “Let’s Make America Great Again” (Ronald Reagan, 1980). Alternatively, we can fill our emotional space with slogans of hope for the future like “Change we need” or simply “Hope” (Barack Obama, 2008). Campaigns, candidates and even presidents come and go, but the undying reliance on words that bring a sense of comfort and hope in the face of threats real or imagined is enduring. As we stand post-election and pre-Christmas, in whom or in what do we hope?

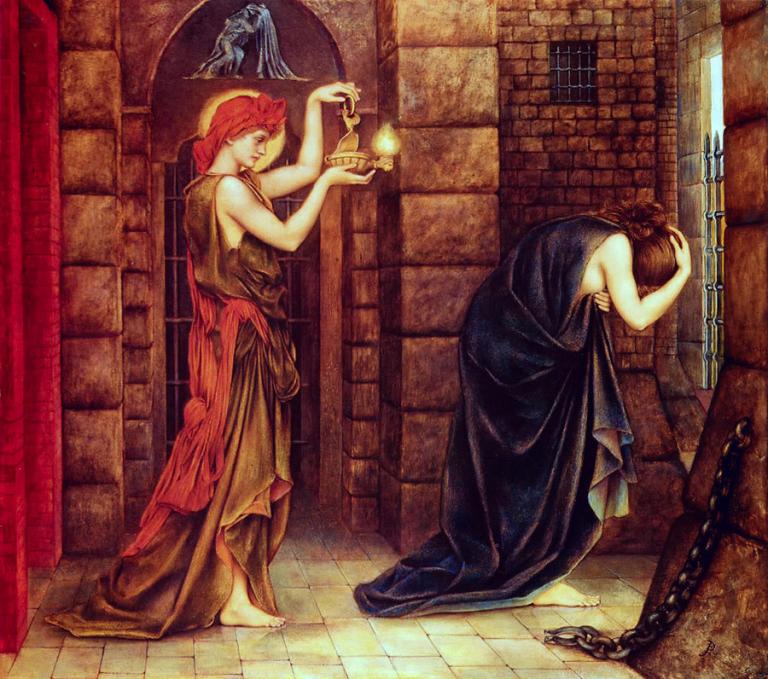

The Letter to the Hebrews addresses a Christian readership living under the threat of extinction. They are not simply experiencing a loss of privileged status. They are not paranoid. They are facing real persecution.

These Christians—often considered to be Jewish (as the epistle’s title was likely intended to convey)—are seriously considering abandoning their newfound faith and returning to or abiding only in the Jewish tradition.[1] One possible reason is that Christianity was no longer tolerated by the Romans, unlike Judaism which was officially recognized and tolerated by Rome (at least until around A.D. 70). If accurate, that is enough for them to feel the lure of leaving the Christian faith and returning to their Jewish roots. These recipients of the Letter to the Hebrews may have felt quite at home in the Jewish tradition to which they had previously belonged—either as Jews, or as God-fearing Gentiles. For those of us who have had a good upbringing and cherished background, we are perhaps tempted to return to our previous home when experiencing extreme discomfort and trauma. We find emotional calm from the storm in the shelter of familiarity.

Not every word from our past is a good word, though. The same goes for Israel’s history. While the featured biblical characters in the Letter to the Hebrews are largely deemed good, there were others recounted in the Jewish Scriptures who were distorted in their vision and abandoned the Jewish faith for selfish or nationalistic ambition. Many turned away to other gods and other loves.

Like the Jewish believers from the Exodus to the Exile, the Christians to whom the author of Hebrews addresses his letter are being tempted to consider campaign slogans of candidates for king who would displace Jesus as Lord. No doubt, some of the slogans were propaganda distortions that manipulated the messages of revered figures from the ancient past. In the face of such temptations, these Christians need a word from the Lord—deep and abiding truth. Only then will they be able to combat such negative campaign rhetoric. So, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews starts his epistle with the following words:

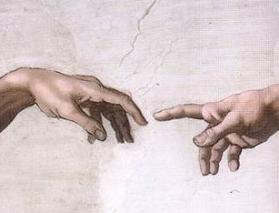

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, having become as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs. (Hebrews 1:1-4; ESV)

As we come to terms with the 2018 election results, and as we move forward toward Christmas this year, in whom do we hope? Perhaps we are even looking past this Christmas toward the U.S. Presidential election in 2020 in search of our ultimate hope. So, I ask again: in whom do we hope?

Without discounting the importance of the political process and what it can entail for human flourishing (in fact, the Christian faith itself is not a-political but political, though in ways different than we often expect), we should place our true hope in Jesus. But why? Because as Hebrews 1:1-4 reminds and reorients us, while God has spoken in many ways in the past, “in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son,” that is Jesus. Because God has appointed him as his heir, no one else. Because God created the world through him. Because he is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact imprint of his nature. Because Jesus upholds the universe by his powerful word, not some campaign slogan. Because Jesus has made purification for sins and has sat down at the Majesty in heaven’s right hand. Because Jesus is as much superior to the angels as his inherited name is superior to theirs.

The next blog post on this subject will seek to address further the matter of the basis and rationale of the Christian hope in Jesus. Building on Calvin’s and Barth’s understanding of the munus triplex (three offices of Jesus Christ), which we find here in Hebrews 1:1-4, we will claim that instead of three strikes against him and Jesus is out, he is “in” as the basis for our hope in the face of apparent persecution and loss of privileged status. Jesus alone is our secure hope because he is the great prophet, priest, and king.

_______________

[1]Franz Delitzsch assumes the audience is Jewish: Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1871-72), 1:4, 20-21. F. F. Bruce also argues for a Jewish audience. See The Epistle to the Hebrews, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), page 6. David deSilva takes issue with Bruce’s position. In commenting on Bruce’s stance, deSilva writes “[Bruce] believes that the author’s use of the OT to sustain commitment to the group proves that Gentile Christians are not in view, for if these were tempted to defect from the church, they would also be prepared to throw away the OT as well, whereas Jewish Christians would not. If their temptation to defect, however, is primarily social (yielding to society’s shaming techniques at last) rather than ideological (rejecting the message about Christ and the texts in which it was grounded), then the OT would remain a valid body of texts from which to elevate ideological considerations over considerations of social well-being. I do not, therefore, find Bruce’s argument necessary, or even likely on this point. The addressees need reminding that ideological integrity (commitment to the worldview and vision of the group) is ultimately more advantageous than social reintegration.” David A. deSilva, Perseverance in Gratitude: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), page 5, note 16).