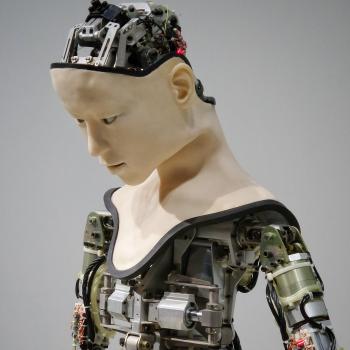

Last week it came out that many scientists want a 5-year moratorium on gene-line editing. This means no editing DNA that might be passed down to your kids. However, a recent piece argued against this. I will dissect the arguments against this to point out why we should have a moratorium.

Top Scientists Want a Moratorium

Stat ran a story titled, “Leading scientists, backed by NIH, call for a global moratorium on creating ‘CRISPR babies.’”

The Chinese scientist who created “CRISPR babies,” He Jiankui, sincerely believed that the research violated neither his country’s laws nor the guidelines of the international scientific community, according to his friends and colleagues. […]

Now, in an effort to prevent another He, 18 scientists from seven countries have called for “a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing” — that is, changing DNA in sperm, eggs, or early embryos to make genetically altered children, alterations that would be passed on to future generations. They say a moratorium should be in place for at least five years.

In a statement, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said that “NIH strongly agrees that an international moratorium should be put into effect immediately.”

The (Bad) Case for Editing Human Germ-line Cells Now

A Moratorium Is Redundant

Already, over 30 countries prohibit this sort of gene editing, either by law, regulation or enforceable guidelines. For this reason, it was quite easy for the director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health to endorse the proposed moratorium – the NIH, the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world, is already prohibited by law from funding clinical applications of gene editing. So a moratorium is at best redundant in those nations.

I think even Schaefer realizes this is a weak argument. If something should be banned, banning it at multiple levels ensures greater compliance. An international ban also prevents some small country from allowing it so they make money off becoming the hub for immoral activity. Or, as Schaefer later admits, it prevents a rogue scientist from seeking out a country that will let him do it.

Moratorium Is a Blunt Instrument

Some researchers remain concerned that a moratorium is an overly crude and arbitrary means of regulating a controversial new technology. While the technology is currently not fit for clinical use, are scientists so certain that it still won’t be within five years’ time? More flexible regulatory frameworks that do not include arbitrary timelines could better adapt to rapid scientific developments and shifts in public perceptions.

This misses the mark in several ways. First, if some radical advancement comes, a five-year moratorium can be revisited. Second, the Church asks, and I think society wants a very high bar for safety before doing germ-line DNA editing. Given the degree of safety we would want before human trials, we would need several long-term trials that simply can’t be done in five years. We would want the mutations passed on over more than a generation or two in mammals. We would want a person to receive these changes on non-germ line cells and look at results 10+ years down the road. And, we would want to see how mammals lived born with germ-line mutations for a decade on more.

We Need Public Consensus

Finally, it’s unclear whether a moratorium is consistent with the democratic norms that the proponents of a moratorium espouse. In particular, they reiterate the idea that researchers should only proceed with germline gene editing if there is broad societal consensus on how to proceed.

But shouldn’t a moratorium itself be subject to the requirement of broad societal consensus?

First of all, the right thing is not always the popular thing. I understand how a democratic society often takes the moral view of the majority, but I wanted to point that out. Second, Schaefer admits that now it would just be initial trails on humans. Yet, according to Pew, 65% of Americans think researching gene-editing on human embryos is taking science too far. Right now, it is explicitly these experiments that are being prohibited: nobody has proposed banning trials with monkeys or on non-germ line cells of consenting adult humans. Most Americans also see the negative consequences of allowing gene-edited babies. Continuing the same Pew article:

A majority of Americans (58%) believe gene editing will very likely lead to increased inequality because it will only be available to the wealthy. Some 54% of Americans anticipate a slippery slope, saying it’s very likely that “even if gene editing is used appropriately in some cases, others will use these techniques in ways that are morally unacceptable.” And, 46% expect it is very likely that gene editing techniques will be used before we fully understand how they affect people’s health.

Catholic Teaching on Gene-Editing

In 2008, the CDF in the Vatican produced Dignitas Personae which spoke of Gene-editing:

It is possible to use gene therapy on two levels: somatic cell gene therapy and germ line cell therapy. Somatic cell gene therapy seeks to eliminate or reduce genetic defects on the level of somatic cells, that is, cells other than the reproductive cells, but which make up the tissue and organs of the body… Germ line cell therapy aims instead at correcting genetic defects present in germ line cells with the purpose of transmitting the therapeutic effects to the offspring of the individual.

After distinguishing the two, the Vatican rules very differently on each.

Procedures used on somatic cells for strictly therapeutic purposes are in principle morally licit. Such actions seek to restore the normal genetic configuration of the patient or to counter damage caused by genetic anomalies or those related to other pathologies.

It then gives warnings to make sure the benefits outweigh the risks. In this way, editing the genes in my arm to kill a cancer tumor would be considered along with radiation or surgical removal based on risks and rewards.

The moral evaluation of germ line cell therapy is different. Whatever genetic modifications are effected on the germ cells of a person will be transmitted to any potential offspring. Because the risks connected to any genetic manipulation are considerable and as yet not fully controllable, in the present state of research, it is not morally permissible to act in a way that may cause possible harm to the resulting progeny. In the hypothesis of gene therapy on the embryo, it needs to be added that this only takes place in the context of in vitro fertilization and thus runs up against all the ethical objections to such procedures. For these reasons, therefore, it must be stated that, in its current state, germ line cell therapy in all its forms is morally illicit.

You will note that the Church has not ruled that in all future cases this will be immoral but, “in the present state of research,” we can’t do therapy as the risks both to the patient and offspring are too high. As these risks carry down through generations, it will take a long time to show sufficient safety. Thus, I cannot imagine this being approved anytime soon.

Conclusion

There are a few additional moral issues.

- As I wrote about back when the first gene-edited babies were produced, scientists are finding that CRISPR is not as precise as they previously thought and often causes mutations far away from where it was intended.

- Unfortunately, current scientific methods done on babies early in development will often result in the baby’s death.

- Also, currently, this has IVF as a pre-requisite.

We should support moratoriums on germ-line editing of humans on all levels: state, federal and international. The current international proposal is 5 years. This is good. However, we should be trying to educate people on this so that society isn’t willing to let gene-edited babies in 5 years either. If these procedures are moral, we still have a few decades of testing and safety before trying them on humans.

Note: I rely on great people like you to support my online writing. Please consider supporting me on Patreon.