Gillete’s recent appeal to the post-#MeToo men’s movement has generated a lot of heat on social media.

Let’s be clear on this point: for Proctor & Gamble it’s about selling razors and nothing more, just as their ad “The Talk” was about selling beauty products. As a publicly traded corporation, an immortal psychopath created by government fiat, P&G is constitutionally incapable of any interest in the politics or philosophy of gender or race beyond how it affects shareholder value. Bill Hicks’s comments about marketing still apply.

As Bret Weinstein pointed out, citing photos of models at a racing event in skin-tight outfits with “Gillette” branded across their rear ends, “Sex sells. Sometimes woke sells. “Sales” is the common factor.”

And yet, if a razor ad is a threat to your idea of What It Is To Be A Man, you need a better version of manhood, my friend. And if in this consumer culture a razor ad gets a few guys to do a little self-examination, to ask themselves what sort of men they want to be and what sort example they want to give their sons, that’s all to the good.

A tangential point of trivia: King Camp Gillette, they guy who started the razor company, was a Utopian Socialist who though that most of the US population should live in one giant city, powered by Niagara Falls and run by a “United Company” in which women would be equal partners.

Anyway. This Gillette moment comes when the American Psychological Association has just issued new guidelines for treatment of boys and men. The APA points out that men experience challenges including higher rates of violence, incarceration, suicide, and substance abuse, as well as academic drop-out, suspension, and expulsion. They associate this with something they refer to as “traditional masculinity ideology”:

Although there are differences in masculinity ideologies, there is a particular constellation of standards that have held sway over large segments of the population, including: anti-femininity, achievement, eschewal of the appearance of weakness, and adventure, risk, and violence. These have been collectively referred to as traditional masculinity ideology.

Now, it should be noted that the APA’s mens’ studies division has since issued a clarification that “When we report that some aspects of ‘traditional masculinity’ are potentially harmful, we are referring to a belief system held by a few that associates masculinity with extreme behaviors that harm self and others. It is the extreme stereotypical behaviors—not simply being male or a ‘traditional male’—that may result in negative outcomes.”

But still, this brings two questions to my mind:

1. Is this “traditional masculinity ideology” a cause or a response to the challenges that men face?

2. Is “traditional masculinity ideology” harmful or maladaptive in itself, or is the problem that these standards need to be balanced by additional values that put them in a healthy context?

Today I’d like to focus on that first question. We’ll look into the second one in a subsequent post.

Fathers And “Soft” Boys

In my role as a martial arts teacher, from time to time I get the impression that a father is bringing his young son to me for training because he is worried about him being “soft”.

I don’t mean that he is disappointed in his son, or does not love him. Rather the impression I get is that the father knows that his son is likely to face direct physical challenges like bullying as well as the social challenges of dominance hierarchies, and he wants his son to be able to deal with them.

In these situations, the boy’s mother usually seems supportive of these aims but it’s the father who says something to me about his concerns. Also let me be clear that I am proud to also teach women and girls, and there is a set of reasons and challenges about training there which partly overlap and are partly different. We may explore those another time, but I want to focus on the boys today.

In reference to the APA’s idea of “traditional masculinity ideology”, these fathers want their sons to be competent in the use of violence, because they foresee them possibly having to fight. They want their sons prepared for risk and adventure, and able to project an appearance of strength rather than weakness.

They want this because they believe the boys will need those characteristics in order to not be pushed to the bottom in a world that can (in their belief) be tough. And I don’t think they’re wrong to think that — but their thinking may be incomplete, as I’ve talked about before. So I feel like it’s a good thing that they end up bringing their sons to me rather than to a more “Cobra Kai” sort of teacher.

Class, Masculinity, And The Hierarchy of Needs

There seem to be class issues involved in the concerns these fathers bring. Again this is a personal impression, I have not collected data about family income or educational attainment; but it seems like the more a father is “working class” the more likely these sorts of concerns are to be present. “Professional class” parents, in contrast, are more likely to be concerned with their kids acquiring self-discipline and confidence, and maybe having an extra-curricular activity to look good on a college application.

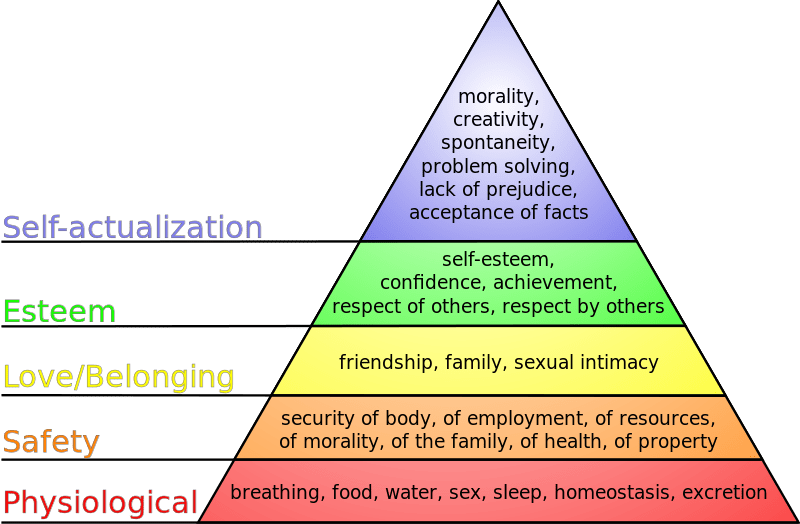

These professional class sons (and daughters), in other words, are starting a little higher up on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The working-class parents are concerned about their sons’ safety needs, where professional class parents are assured their kids will be able to meet those and are working on esteem needs.

It is problematic that our talk about gender tends to leave out the very different experiences of men of different classes. It is true that when you look at corporate boardrooms, you disproportionately see men — upper class men. But it is also true that when you look at our prisons, or at the lists of those killed in the military or through violence or on the job, you disproportionately see men — men of the lower classes.

(On a side note, this is another reason framing exemption from the penalties of sexism as a “privilege” is problematic: not only does it confuse rights with privileges, but it also draws incredulity from many low-status individuals when they are described as “privileged”. It’s ineffective rhetoric and should be eschewed.)

It seems to me that these APA guidelines are in part upper-class professional men looking down on a version of masculinity that is lower on the hierarchy of needs than theirs.

It’s true also of that Gillette ad: except for the clip of real-life hero Ibn Ali Miller breaking up a fight on the streets of Atlantic City, the male characters in the ad seem to be pretty middle class. (See them line up behind their grills along those suburban wooden fences.) And I will bet you a nickel the advertising “creatives” who created it do not have dirt under their fingernails or calluses on their hands.

Of course class is not an excuse for bad behavior; and as the Kavanaugh hearings reminded us, upper class boys and men can be dangerous sexist pigs. Indeed much of the #MeToo movement has been about revealing the bad behavior of powerful men in the upper classes.

But it seems to me that if we’re going to talk about the problems of “traditional masculinity ideology”, we need to see how that ideology is sometimes an attempt (however flawed) to deal with real problems in men’s lives. And if we want men to “do better”, we have to propose alternative solutions to those problems.

That’s a task we’ll leave to a future post.

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.