“Much obliged” is an old-timey sounding way of saying “Thank you.”

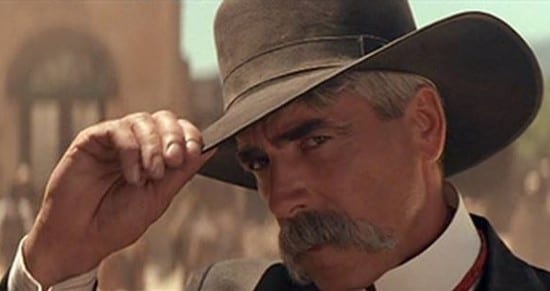

That makes it harder for me to incorporate this phrase in my casual daily use. It still sounds anachronistic and awkward in what remains of my Jersey accent. In my voice, “Much obliged” sounds as weirdly unnatural as it would if I were to address strangers as “Pardner.” It sounds like I’m doing a bad impersonation of Sam Elliott or Timothy Olyphant in Deadwood.

But I’m going to figure this out because I think this is important. Very important. Because a big chunk of what’s ailing and broken here in America is the very thing expressed in that old-timey expression “Much obliged” — the failure to see the necessary connection between gratitude and obligation.

The break in that link is what allows the politics of resentment to flourish. And it’s what has allowed the politics of resentment to replace religion in so many of our churches. Ingratitude is the American disease.

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving, a day marked by language so abstract it says almost nothing. Worse than nothing, really, because these airy abstractions lull us into thinking we have said or done something meaningful when we haven’t.

What are these “thanks” that we give? To whom do we give them? Ask anyone, even yourself, to define “thanks” and you’ll likely wind up on a merry-go-round of circling generalities. “Thanks if an expression of gratitude.” And what is gratitude? “Gratitude is thankfulness.” And how is this thankfulness expressed? “By saying ‘thank you.'”

Linguists and grammarians have more precise ways of describing the fluffy essence of “thank you” and “thanksgiving,” and it’s fascinating to read their sharp discussions of “performative utterances” and the like. But none of that cuts to the heart of the matter which is that I can “give” you my “thanks” and, well, what have you got? That and $3 will get you a cup of coffee at Starbucks.

So “Much obliged” isn’t really just another way of saying “thank you,” it’s a way of saying more than “thank you.” Or of making the abstraction of “thank you” closer to something concrete by reminding both of us that gratitude is meaningless unless it entails obligation.

That still doesn’t help with the Sam Elliott problem and my inability to casually incorporate “much obliged” into my daily language without feeling like I should also be wearing a ten-gallon hat.

Someone suggested “I owe you one” as a less old-timey alternative, and I think that’s also better than the ethereal fuzziness of “thanks.” But it’s not quite as expansive as “much obliged.” It recognizes the obligation implicit in any meaningful expression of gratitude, but also injects a transactional note that misleadingly limits that obligation. Gratitude doesn’t just mean I owe you one — it means I owe more than one and more than just to you. It means I am forced to admit, in the biblical phrase, to being a part of “an inescapable network of mutuality.” I am indebted — not just to you, but to anyone and everyone I may encounter who finds themselves in need of assistance as I just was. You have shown me favor or done me a favor, and gratitude requires that, when the opportunity arises, I do the same for you or for anyone else who might require it. Freely I have received and, therefore, freely I must give. The debt is perpetual and mutual and boundless. Anything less is ingratitude.

Gratitude is not a ledger keeping a balance of transactions. We are all much obliged, but the obligation entails more than reciprocity. Gratitude is magnanimous, not just thank-full, but overflowing.

If you think all this obligation sounds burdensome, you’re not wrong, exactly. It is, in a sense. It’s also infinitely less burdensome than ingratitude — which is the only alternative.

Ingratitude is misery. It renders one incapable of anything other than misery and the kind of inconsolable self-pity that one is forced to resort to when one refuses to allow that pity its proper outlets to others. To choose ingratitude, Jesus said — to refuse to be “much obliged” — is to consign oneself to be “delivered to the tormentors.” (Ingratitude is a major theme throughout the Bible — in the parables of Jesus, the prophets, even the Psalms and Proverbs. And the recurring emphasis, throughout, is that the consequences of ingratitude are terrifying.)

As I’ve said before, this is not the worst or most urgent problem created by ingratitude. The harm that it does to the ungrateful is not as much of a priority as the harm it causes them to do to others. But it may be easier to get those trapped in the bondage of ingratitude to see the harm they’re doing to themselves than it will be, at first, to get them to see the harm they are doing to others. Like Ebenezer Scrooge or Zacchaeus, they’re perhaps more likely to recognize their need for repentance and the obligations of gratitude when the focus is on the consequences for them.

This is why I’ve taken to avoiding the term “white privilege” and speak, instead, of white ingratitude.

Anyway, tomorrow is Thanksgiving Day and I work in retail, so for us, it’s showtime and I’ve got to run. But if you’ve read this far, and if you’re still reading this blog even now, long after the Barons of Social Media have decreed blogs dead, I want to express my gratitude to you. Thank you. I am very much obliged.

Happy Thanksgiving.