I’m going to share this story again, because it’s again important and relevant. It always is, I suppose. This is the story Matt Giuffrida told me about how he came to work for the American Baptist Churches.

Or, really, it’s the story Matt didn’t tell me. I think he thought he did, but when it came to the central part he just stopped talking and stared at the floor.

My first job after college, 1990, was an internship in the ABC’s “National Ministries” offices in Valley Forge. I had a little cubicle-desk right next to “Matt’s girls.” That’s how they introduced themselves, ignoring Thelma, our boss. when she corrected them to say women.

These were four terrific people who were passionate about their jobs even though, when they first started, they’d had no idea what they were in for. They’d seen an ad somewhere for a secretarial job in an office, filing and phone calls, and only later learned that it was for the denomination’s office on immigration and refugee resettlement. They worked with Matt. So at some point, when they first started, Thelma probably told them what she told me: “You need to hear Matt’s story. You need to understand what he does and why he does it.”

Thelma had been making Matt tell that story for years, but he still never quite managed to figure out how to do it.

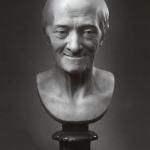

Matt Giuffrida was a painfully shy, soft-spoken man. He was not a public speaker. He was barely a private speaker, and not a natural storyteller. But he had the first part of his story down pretty well, the part about being an 18-year-old who enlisted in the Army during World War II. “I was in the Combat Engineers, hmmh?” He often tacked that little murmur of vocal flair on the end of sentences. It meant something like, “Do you follow me?” It reminded me of Treebeard the Ent.

He explained he was a “civil engineer,” part of a corps that followed the infantry as it battled its way across Europe. His job, as he explained it, was to fix things as best they could to restore some semblance of order and safety in towns and territories liberated by the Allies. Sometimes that meant physical repairs, like rebuilding literal bridges, but it also involved just helping civilians get back on their feet, ensuring they had access to enough food, water, medicine, and shelter that they’d be able to begin the long work of rebuilding their communities.

That was the job, he said, fixing everything that needed to be fixed, hmmh?

And that was the job he had at age 19, the orders he was given, in 1945, when the Army arrived at the concentration camp. “It was …” he started to say, then stopped and paused for a long, awkward moment before trying again. “They liberated the camp,” he said, “and then it was up to us to …”

And then he just stopped completely, just closed down, staring at the floor silently.

A full painful minute went by.

Two minutes, maybe three, before he spoke again. “And so,” he said, looking up from the floor and the past, a quick smile flinching across his face. “And so a few years later, when I was back home, I knew what I needed to do, but I didn’t know where to start. Hmmh?”

I don’t think he quite realized he hadn’t been speaking — that this key part of his life’s story hadn’t been described or told. But that didn’t really matter anyway. It had been communicated. His silence had been loud and clear.

From there the story was back on track, back into the confident, well-rehearsed and upbeat parts where after he finished college the American Baptist Women’s Home Mission Society commissioned him as its first missionary in the ministry of refugee resettlement, a job he performed for nearly four decades, overseeing the resettlement of more than 80,000 refugees from all over the world.

He was able to tell that part of the story — about his life’s work as an advocate for desperate strangers, and about his years-long legal battle against the U.S. government on behalf of Central American refugees (a case soon to be settled in his favor). But the context for all of that was the part of the story he was unable to tell — the unspeakable things he’d seen 35 years earlier, that haunted him and drove him for the rest of his life. He was still churning.

Matthew Giuffrida retired in 1993 and died in 2003. He was a quiet, humble man and you’ve probably never heard his name before. Most of those 80,000 refugees he helped resettle never heard his name. Nor did the thousands of others resettled thanks to the “ABC status” he fought to win them.

And so, hmmh?