“Debate” is a parlor trick.

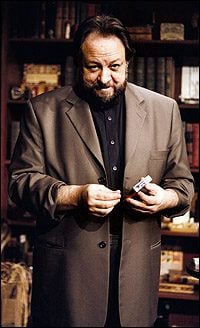

That doesn’t mean I don’t admire the skill, practice and dedication such showmanship requires, but I’m less impressed watching someone trained in “debate” deftly handling their arguments than I am watching, say, Ricky Jay handling a deck of cards.

Jay’s performance is better because, unlike those practiced in debate, he’s not suffering from shut-eye. He knows he’s performing a trick and — even if his patter may playfully suggest otherwise — he knows that we know it too. We watch the cards dance in his fingers, disappearing and re-appearing as if by magic, but we all know and accept that it isn’t really “magic” — just the remarkable, dazzling, entertaining execution of a clever trick.

Any magic act would be far less entertaining — and far less impressive — if the “magician” were genuinely trying to convince us otherwise. Or if he seemed foolish enough to believe otherwise himself. We’ll play along with magical powers as the conceit of a trick, but only as a conceit. I’m amazed and delighted at the skill with which Ricky Jay manipulates a deck of cards, but that skill would be cheapened and that amazement diminished if it required either the performer or his audience to believe that something more than skillful manipulation was at work.

And that’s the problem with debate. It invites the audience — and even more so the performers themselves — to regard it as something more than simply the skillful execution of tricks. The audience is asked to believe that this prestidigitation is meaningful, that it reveals truth. And, even worse, it asks the performers themselves to believe that. It convinces them to be tricked by their own trickery. These skilled illusionists become delusionists, infected by the old shut-eye. They are tempted to believe their own patter and wind up convincing themselves that the parlor trick of debate has something to do with the open-minded, single-minded pursuit of truth.

That’s not what debate is about. Debate is about winning. That’s why they keep score — why there’s such a thing as debate teams who compete against other teams. They compete for trophies and titles, not for truth.

The rules of debate say as much, otherwise the outcome of every such competition would be predetermined by the initial assignment of sides. The whole game is a construct designed to ensure that neither side has an advantage. The only way for the contest to be fair — or to be any fun — is if it is conducted in such a manner that it doesn’t ultimately matter whether or not the side being argued is ultimately true. It is a construct designed, quite effectively, to segregate truth from winning — a way of “scoring” arguments irrespective of any necessary correlation to anything actual. The winning tactic thus may be a maneuver that effectively conceals, evades, deflects, buries or obscures any truths that might be damaging to the argument of one’s assigned side.

Such debate competition can be useful training for anyone interested in pursuing truth outside of the competitive construct of such contests. Learning to employ such tactics of deflection, concealment and obfuscation can be an excellent way of learning to recognize their use outside of the debate arena — i.e., in real life, where truth is what matters and not just scoring points. And learning to counter such tactics is eminently practical training for both the artificial setting of the arena and the actual setting of the real world.

But the value of such training is lost if those trained in debate become infected with the shut-eye — if they begin to confuse winning with reasoning, point-scoring with truth. When that happens, the performers forget they are performing. They are tricked by their own tricks.

This is why I find so much of the so-called “Christian apologetics” so disheartening. That’s true for the clumsy, botched sleight-of-hand of a Ray Comfort — aces protruding from his sleeves and a handkerchief peeking out from beneath an oversized, mismatched thumb tip as he proclaims “Ta-da!” and takes his bow. But it’s just as true for the masterful manipulation of a skilled performer like William Lane Craig. I’ll happily applaud when he opens the sealed envelope from inside the corked bottle and reveals the very playing card I had chosen at random, moments before. Bravo! Well done! Wonderful trick! But, no, it’s no reason to believe in actual magic. Expert showmanship isn’t the same as the pursuit of truth — even if the showmen themselves seem to have forgotten the difference.

When Ray Comfort challenges someone to a debate over the truth of Christianity, I wince because I am a Christian and I know that Comfort is most likely going to “lose” that debate, leading some to the mistaken conclusion that this indicates something meaningful about the truth or untruth of what I believe. When William Lane Craig challenges someone to a debate over the truth of Christianity, I wince because I am a Christian and I know that Craig is most likely going to “win” that debate, leading some to the mistaken conclusion that this indicates something meaningful about the truth or untruth of what I believe. Such winning and losing at the game of debate is as meaningful as winning or losing in a poker game with Ricky Jay. (Note: You will lose.)

This little rant was prompted by Libby Anne’s post earlier today on the “Brainwashed shock troops” of the fundamentalist homeschooling movement and by Rachel Slick’s guest post at the Friendly Atheist earlier this week, “The Atheist Daughter of a Notable Christian Apologist Shares Her Story.” Both posts are in the form of what we evangelicals call a “personal testimony” — albeit in the opposite direction.

What’s striking to me in both testimonies is the way in which trickery and truth are confused by so many fundamentalist parents. They come to confuse winning with meaning, and convince themselves to believe that their manipulation really is magic. But to quote C.S. Lewis — someone who flirted with the old shut-eye himself and later came to regret it — “reality is harsh to the feet of shadows.” Outside the artificial arena of the game of debate, there’s no panel of judges keeping score and awarding points for clever tricks. In the real world, everything will be tested. So test everything. And hold on to the good.

The good — not whatever wins or whatever scores points.

Rather than training their little fundie “shock troops” in the craft of debate, these parents would be better served — and their children would be better served — to teach them the practice of dialogue. “Debate” can carry you only until you encounter a situation in which your tricks don’t matter. Or until you encounter someone who knows better tricks than you do.

These homeschooling parents should scrap all these debate teams and replace them with something far harder but far more practical for real life in the real world: Improv.

I’m deadly serious about that. I realize improv training is trendy and that, as Ayun Halliday writes, “There’s big money in teaching corporate executives the rules of improvisation.” But even if I dread the crimes against comedy that would likely be committed by legions of fundamentalist homeschooling improv troupes, the exercise would require them all to learn and to practice and to acquire the art of listening.

And that skill better equips one to seek and to find the truth than any amount of debate trickery ever could.