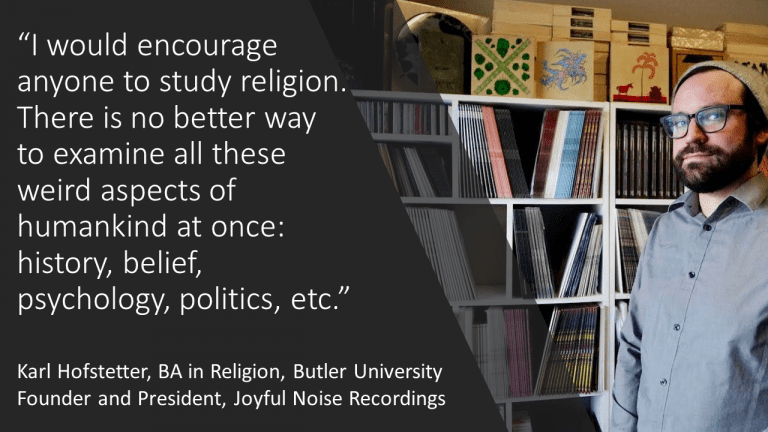

Let me start this post with a quote from an alumnus of the Religion program at Butler University, something that he said on Facebook. Karl Hofstetter provides one of my favorite answers to the question “What can you do with a degree in religion?”

This post began several years ago as I started collecting posts related to the different sorts of things that “biblical studies” can sometimes be in different contexts, a state of affairs that creates confusion among some outside of academic circles. At seminaries, the approach to biblical studies can be decidedly theological. This is true whether one is talking about a conservative seminary that restricts faculty and students from pursuing the application of, or embracing the conclusions of, methods such historical criticism; or a liberal seminary that is completely on board with those methods. The latter overlap much more with the literary, historical, and postmodern approaches that are typical of secular scholarship, and can participate to a large extent in a shared endeavor on that basis. Yet there is still a distinction inasmuch as at seminaries, the aim is to serve the needs of church or synagogue.

Also on this topic, why everyone should major in (or at least take a course in) religious studies, Jonathan Bernier on Biblical studies as theology, Henry Cadbury and Larry Hurtado on learning biblical languages, and Ronald Huggins’ advice to doctoral students

Krista Dalton wrote about “Creative Pedagogy in the Biblical Studies Classroom.” Here’s how her piece begins: “Teaching a Bible class typically involves disrupting my students’ preconceptions—illuminating historical context, complicating the composition of stories and manuscripts, and interjecting ancient meaning obscured by time and translation. With such focus on uncovering the Bible’s original context with a scholarly lens, I devised an end-of-semester assignment that would allow for my students’ own textual experimentation.”

Also, the teaching of the Bible in public schools has been in the news lately. And from this review of Jacqueline Vayntrub’s book Beyond Orality:

Beyond Orality is an indispensable work on aesthetics, hermeneutics, and book history for the biblical philologist. As a work of methodology, however, it is even more important given the idea it represents. Vayntrub demonstrates that even our most basic modern literary categories, such as “prose” and “poetry”, are not probative universals but the accidents of history. In a sense, Vayntrub has found a way to make her sources do criticism, a development that philology has awaited since the colonial critique. Beyond Orality reintegrates theory and philology in an enviable but imitable way, giving scholars of ancient literary traditions—be it Akkadian, Sanskrit, Chinese or Kʼicheʼ—all the tools they need to adapt her approach to other ancient textualities.

Have a listen to this podcast by Larry Hurtado. See also:

There were also a couple of great guest posts by Rev. Dr. Judy Siker on Bart Ehrman’s blog. In one of them she wrote:

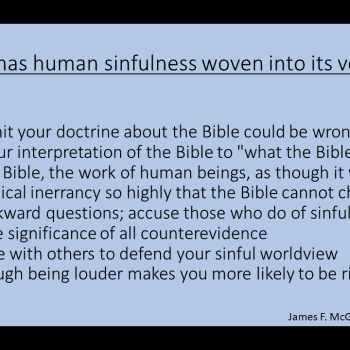

A scholarly approach to the Bible will without doubt demonstrate the inconsistencies in the Bible, will introduce the student to issues of authorship and dating and word use and definition. This is all intriguing, well to me, it is. If, however, one comes to the Bible with the idea that it can only be considered sacred text if it is historically accurate, factual, without error or inconsistency, then by all means the scholarly approach is anathema. If one comes to the Bible believing that it contains the answers to all of today’s social, cultural, even scientific questions, then by all means the scholarly approach is anathema. If one comes to the Bible believing that the words in the text came straight from God’s mouth to the writer’s ear, then, once again, and by all means the scholarly approach is anathema.

I understand why these approaches are held by some. If one works hard enough there is little room for questions (often equated with doubts). But as I stated earlier, I live in the questions. Not only do I live in the questions, but I believe we are meant to live in the questions. If there is one thing I’ve learned across the span of my lifetime it is that I will always have more questions than answers. Inevitably as I discover answers in my searching, it leads to yet more questions. But I have come to believe strongly that living the questions is really living.

See too:

The State of New Testament Studies: Dennis Edwards on Hermeneutics