Before jumping into the theme of this blog, allow me to thank fellow Patheos bloggers Mark Shea, Mary Pezzulo, and Kate Cousino for their encouragement to return to the Catholic blogosphere via Patheos, as well as new friend and popular student finance blogger Martin Dasko whose enthusiasm from a non-religious perspective also inspired to start blogging again. And a big thank-you to Rebecca Bratten Weis for her hard work behind the scenes to make this happen, despite my eight-year absence from Catholic media.

Yet when speaking of Patheos bloggers, I once again find myself indebted to friend and sometimes foe Dave Armstrong. A few years ago, Dave invited me to be part of an online dialogue between Latin Catholicism and Eastern Catholicism as Orthodoxy in communion with Rome. I had first met Dave online during the rise of the Catholic apologetics movement in the 1990s. Dave’s work was instrumental in drawing me back to full communion with Rome; first as a Pentecostal, and second as an adherent to a particular branch of Latin traditionalism that at the time mistrusted the Second Vatican Council and the Roman Pontiffs elected following the council.

To this end, I am forever grateful to Dave for helping me understand the beauty and necessity of full communion with the Roman Catholic Church: especially as a Catholic who, for the past 12 years as of this writing, has belonged to what historically was founded as an Eastern Orthodox Church (i.e., prior to restoring full communion with Rome at the Union of Brest). Additionally, I would like to thank our mutual friend Fr. Deacon Daniel Dozer, whose analogy of Eastern Catholics as the children of divorce is one I often find myself using: especially when trying to explain Byzantine Catholicism as Orthodoxy in communion with Rome. Like most children of divorce, one often feels forced to choose between parents, used as a pawn by one or rejected by the other, when one’s deepest desire is to see mom and dad reconciled under one roof.

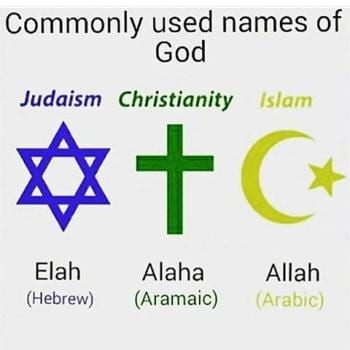

This last point is where I would begin to explain Byzantine Catholicism as Orthodoxy in communion with Rome. The division between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy is unique among divisions within Christianity. For instance, unlike other splits (Anglicanism, Russian Old Believers, Protestantism, Old Catholicism, etc.), there is no clear date for when Rome and Byzantium passed from estrangement into schism. 1054 is the conventional date cited by many secular and ecclesiastical historians. Nevertheless, this was a mutual excommunication between persons, not Churches; and one that was soon reversed.

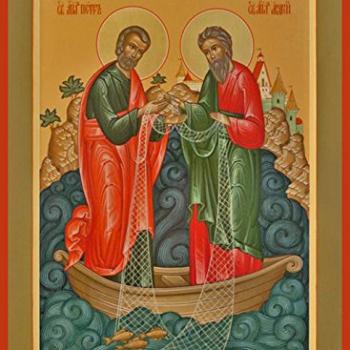

Yet even if 1054 had marked a schism between Churches, those two Churches would be Rome and Constantinople. What about the Church of Antioch? Antioch – the other great apostolic see founded by St Peter – happens to be the see that has suffered most from the division between Rome and Constantinople. Not having been party to the dispute of 1054, when does the Church of Antioch become party to the alleged schism?

And why 1054? Was good faith between East and West not broken in 800 when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor? Or in 863 when Pope Nicholas I attempted to depose St Photius the Great as Patriarch of Constantinople? Or 1009 when the Patriarch of Rome stopped appearing in the Diptychs of the Church of Constantinople? What about the riots of 1182 in Constantinople when Greeks massacred Latins? What about 1204 when Latin crusaders sacked Constantinople and butchered Greek Christians until their blood ran in the streets? Or what about earlier misunderstandings that led to division between the Church of both halves of the Roman Empire and the Assyrian Church or the East, or the Oriental Orthodox (aka non-Chalcedonian) Churches?

In short, there is no one moment that historians and apologists can pinpoint as to when Catholics and Eastern Orthodox ceased to be in full communion with each other. Rather, communion between Rome and Constantinople broke down over a period of four centuries. We should take a moment to ponder this reality. With respect to my Reformation brothers and sisters, the breakdown of communion between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy took longer than the age of most Protestant denominations.

This raises another unique aspect of the division between Orthodoxy and Catholicism: communion broke down. Catholics did not leave the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox did not leave the Catholic Church. Rather, communion between the two largest Christian ecclesiastical bodies – a communion that had existed since apostolic times – broke down. It did so over a 400-year period, with each laying claim to a common tradition from apostolic times.

Which in turn leads us to another question that ought to trouble the conscience of all Catholics and Orthodox today: Given that Catholics and Orthodox celebrate the same Eucharist (although, sadly, we are still some years away from concelebrating it) is the Great Schism in fact a schism between two Churches? Or is it a schism within the same Church?

Here I can only quote the words of Archbishop Elias Zoghby in his book We Are All Schismatic: “In other words, neither the Roman Church nor the Orthodox Church were born from schism. After they separated, they have prolonged in their own way the Church of their Fathers in the faith.”*

Because both East and West lay claim to the same undivided Church of the first millennium, the same Eucharistic Christ, and the same apostolic tradition, it is imperative that each seek to better understand the other in order to restore the bonds of charity and full Christian communion between us. And to this I would also add our Eastern Christian brothers and sisters among the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Assyrian Church of the East.

*Translated by Philip Khairallah; Newton, Massachusetts: Diocese of Newton Education Services, 1996; p. 9.