Samhain, All Hallows’ Eve, marks the time between time, the world between the worlds, when the veil is thin, and beings cross back and forth over the Great Divide.

It is late October in New Orleans, with high temperatures are in the low-mid-80s, going down at night to the mid-high 60s – not impressive to those of you living in more northern climes, but a great relief to us here. Until the end of September, we were sweltering in the 90s with no relief even at night. Welcome to autumn in the Crescent City, the season between Brutally Hot and Uncomfortably Cold.

Across the city, preparations are being made for Halloween. In neighborhoods rich and poor, residences are draped in fake cobwebs in white, gray, and fluorescent green, yellow, orange, and purple. Grocery stores, farmers markets, and even Walmarts are stocked with giant bins of pumpkins, bales of hay, gourds, and scarecrows both whimsical and scary — and what seems like tons of candy, which will be promptly marked down on the morning of November 1st.

Party stores sell pretty and ugly witches, plastic jack o’lanterns, bags for hauling huge amounts of Halloween treats, and a huge variety of costumes and masks for kids. The year-round adult costume shops (yes, New Orleans has year-round adult costume shops that do brisk business year-round with peaks at Halloween and Carnival) offer sexy, funny, scary, or racist costumes. (Please don’t wear blackface or yellowface or brown face or redface for Halloween, or ever!)

The gay community has their own celebration, with creative costumes that will be paraded down Bourbon Street with great ceremony on Halloween night. In some cases, over a thousand dollars will be spent for one night of glory.

For the city’s Roman Catholics, practicing and/or lapsed, Halloween brings traditional duties of cleaning and decorating the family tomb in New Orleans’ above-ground cemeteries for All Saints’ Day, the city’s version of the Day of the Dead. The custom in the past was to bring brooms to spruce up the tomb, re-whitewash it, decorate it with flowers and then spend the day picnicking and visiting. Hardly anyone today whitewashes, but it’s true that from October 30-November 2, the city’s cemeteries are crowded with people bearing pots of chrysanthemums, the flowers of the dead. (Woe betide the uninformed who try to give these to a living person!) The tradition is so entrenched that even the Jewish cemeteries are visited over this time.

There are still cemeteries in the exurbs of New Orleans where devout loving families will spend the night of October 31st-November 1st at the ancestral tomb, bedecked with flowers and food and candles. But this tradition has fallen away in the city, as the Catholic archdiocese struggles with issues of theft and vandalism. (There are unscrupulous sellers and collectors who trade in stolen art from New Orleans historic cemeteries.)

The problem is especially acute in the city’s oldest extant consecrated graveyard, St. Louis No. 1, where some of the city’s historic figures are buried — Dominique You the pirate-hero of the Battle of New Orleans, Paul Morphy, the first U.S. chess champion, and The Widow Glapion (La Veuve Glapion on her tombstone). She is better known by her maiden name, Marie LaVeau, the city’s most celebrated Voodoo queen (priestess) of the 19th century (1794-1881). Bedeviled by devotees and curious tourists defacing her tomb with X’s and leaving offerings of all kinds to either entice or thank her for favors granted, the archbishop closed the cemetery to the general public, allowing entry only to those who can prove family buried there or to those who have paid a tour guide licensed by the archdiocese (for a fee, of course).

During The Lady’s lifetime, her practice of both Roman Catholicism and Voodoo raised no eyebrows. She was a communicant at St. Louis Cathedral, well-known to the rector. (She had been baptized there as an infant by a Spanish priest known to his French parishioners as Pére Antoine.) Her rituals on Bayou St. John were well attended by both black and whites, and her charity made her a beloved figure. Her cortége in 1881, was reportedly followed by thousands of mourners. There was no contradiction between Catholicism and Voodoo in those days, but today the archdiocese staunchly denies her involvement in pagan practices (as do her Creole descendants).

Despite this official denunciation of the practice of honoring Marie LaVeau as a voodooiste, it remains true that practices of “folk Catholicism” or syncretized Catholicism-Voodoo lives on in New Orleans, so far unmolested by the archdiocese. Single young woman still walk on their knees to the shrine of St. Ann to ask for a marriage. On Good Friday, many make what they call a novena, visiting nine churches in one day and venerating the exposed Cross. (Many churches leave paper towels so that you can wipe the lipstick off Jesus’s feet.) St. Roch Cemetery features a chapel with walls hung in gratitude with replicas of body parts that the pious believe have been healed. People of all races and faiths might burn a Money Candle to help solve financial challenges. And those with a house to sell see nothing amiss with burying a small statue of St. Joseph in the front yard to speed the sale. (It is thought he’s uncomfortable in that position.) Not one of these can be justified as orthodox Catholicism, but thrive here, in this city between the rest of the U.S. and the Caribbean.

This Samhain we struggle with other “between the world” scenarios. Since The Storm over ten years ago, thousands of new (white) people have flocked to the Crescent City, attracted by the marketing of the culture, food, music, and what (to them) is a lower cost of living. They have swarmed formerly mixed-race working class neighborhoods, forcing higher rents and renovations of double houses into single residences, thus forcing out original residents. In these gentrifying neighborhoods, not yet middle class and yet no longer affordable for the poor and working classes, new residents, once drawn by local culture, make complaints to officials about noise (music played on the streets by brass bands).

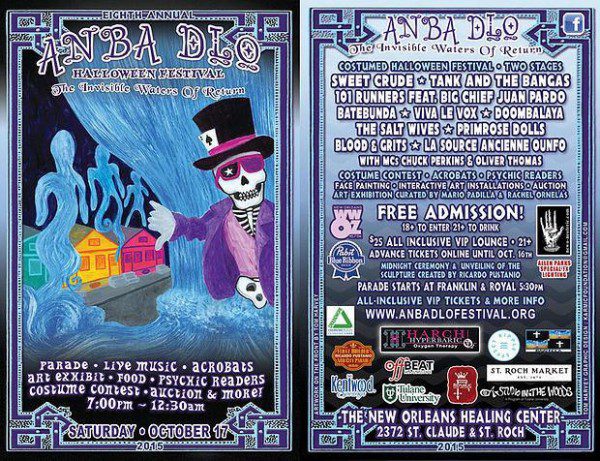

In one gentrifying neighborhood, a white woman from Maine of Jewish heritage who claims to be an initiate into Haitian vodou and her husband, a rich real estate developer, have established a “Healing Center” in an abandoned furniture store, with a grocery co-op (featuring prices the original neighborhood residents cannot afford) and a vodou shop, as well as a restaurant, performance space, art gallery, a fitness center, and a satellite police station.

Every year at this time, the Center throws a festival called Anba Dlo (“Under the Water” in Haitian Kreyol). Past years celebrations were ticketed, but, perhaps in response to neighborhood complaints, this year the event is free. There’s an art exhibit, including the unveiling of a sculpture of a vodou orisha, a dance with live music (VIP tickets to the balcony are $25 each where, it is said, you can “rub shoulders” with the artists), and of course, a parade. (All important occasions in New Orleans involve a parade; this is practically a requirement.)

The Jewish vodou priestess from Maine regularly hosts public rituals, both at the home she shares with the developer and on a bridge over Bayou St. John. (If you Google “voodoo rituals, New Orleans” you will find dozens of photographs; you may be surprised by the crowds of white people led by a white woman for a religion whose roots are in Africa and Haiti.)

I am a Unitarian Universalist minister, a 7th-generation New Orleans white Creole, a practitioner of New Orleans cultural voodoo (I’m not an initiate and don’t think it’s my business to seek it), a liberal Christian, a social justice organizer/activist. I live in Gentilly, a neighborhood that has been mixed-race since its founding in the 1920s. In my spirituality, my culture, and my life, I live between worlds.

Living between the worlds, between races and cultures, between religions, between tensions of run-down houses and expensive renovations, between long-time residents who’ve (literally) weathered the storm and inexperienced newcomers, between the demands and the needs of the living and the dead, requires a double consciousness, a sensitivity to nuance, an awareness of ambivalence and ambiguity. Those of us with privilege don’t always seek out those qualities, or even recognize their necessity. May we do that this Samhain and always.

Rev. Melanie Morel-Ensminger is an 8th-generation New Orleans native. She was ordained a Unitarian Universalist minister in 1993, and has served UU congregations in Tennessee, New Zealand, and New Jersey, before returning home to New Orleans post-Katrina to serve her home congregation 2007-2013. She describes her theology as “Pagan-Christian-Humanism- Buddhism not always in that order.” She and her husband Eric, a trumpet player, live permanently and forever in the Crescent City, not far from Lake Pontchartrain, where Marie Laveau once led Voodoo rituals.