What is the difference between a dead dog and a dead chemistry professor lying in the middle of the road?

What is the difference between a dead dog and a dead chemistry professor lying in the middle of the road?

I’ve been at the American Chemical Society meeting in Boston all week – so there have been plenty of chemistry professors around. As far as I know none were lying in the middle of the road. These meetings are always a good chance to reconnect with old friends and to learn what other groups are doing. This week I had the chance to reconnect with a professor from my graduate school days. I posted on his book – Science and Christianity: Conflict or Coherence? a couple of years ago, but it seems appropriate to repost it today.

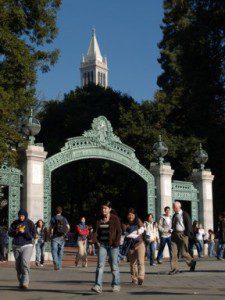

Henry (Fritz) Schaefer was a professor of chemistry at the University of California Berkeley for 18 years (1969-1987) before moving to the University of Georgia, where he has now been for almost 30 years. I was a graduate student at Berkeley when Fritz was on the faculty and participated in a lunch gathering he had with Christian graduate students for a year. His influence as a Christian and a productive and respected scientist was an invaluable example for me.

This book arose from a series of lectures he has given over the years. He got started lecturing on science and Christianity in response to an incident from his first experience teaching freshman chemistry at Berkeley in January 1984. To cover time after a bit of a technical failure with an expected demonstration … well let’s read his own telling of the story:

I said, “While we’re waiting for the moles, let me tell you what happened to me in church yesterday morning.” I was desperate. There was great silence among those 680 students. They had come will all manner of anticipations about freshman chemistry, but stories about church were not among them!

At least as surprised as the students, I continued, “Let me tell you what my Sunday School teacher said yesterday.” The students became very quiet. “I was hoping the group at church would give me some support, moral spiritual, or whatever, for dealing with this large class, but I received none. In fact, the Sunday School teacher first told anecdotes about his own freshman chemistry instructor, who kicked the dog, beat his wife, and so on. Then he asked the class, in honor of me:

“What is the difference between a dead dog lying in the middle of the road and a dead chemistry professor lying in the middle of the road?“

The class was excited about this and I hadn’t even gotten to the punch line. They roared with laughter. … “the difference between a dead dog lying in the middle of the road and a dead chemistry professor lying in the middle of the road is that there are skid marks in front of the dead dog.” It was a new joke at the time, and the class thought it was outstanding. (p. 3-4)

After the class a number of students came down to talk with him – several of whom simply wanted to know what he had been doing in church. Some of the students asked if he would give a lecture on the topic – the first such lecture was in April 1984; the 400th in the summer of 2016 (from a listing in Appendix B of the book). I was a TA for freshman chemistry one of the terms Fritz taught the class – quite possibly January 1984; the timing is about right.

The lectures are interesting. His story of his journey to faith as a young professor is fascinating (From Berkeley Professor to Christian). I disagree with his conclusions in the chapter Climbing Mount Improbable, Evolutionary Science or Wishful Thinking. Fritz takes an old earth, progressive creation view. He rightly points out the confusion surrounding the origin of life, but I find the evolutionary mechanism for the diversity of life far more persuasive than he suggests. He makes an important point however. This disagreement is not over an essential of the Christian faith. For example, Francis Collins and John Polkinghorne are included without reservation in his lists of scientists who are Christians. Fritz also takes a somewhat more conservative Presbyterian view (PCA I believe) on some issues than I do – but again not essentials of the Christian faith.

Scientism. I’d like to conclude this post by looking at one of the other chapters: C.S. Lewis: Science and Scientism. In this chapter he digs into the space trilogy (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength). These books look at the out-workings of “slavish scientific materialism.”

Scientism. I’d like to conclude this post by looking at one of the other chapters: C.S. Lewis: Science and Scientism. In this chapter he digs into the space trilogy (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength). These books look at the out-workings of “slavish scientific materialism.”

Scientism isn’t a common word today – reductionism is more common and conveys something of the same image today. Concerning scientism: “Webster’s second definition fits Lewis’s usage well; “a thesis that the methods of the natural sciences should be used in all areas of investigation including philosophy, the humanities, and the social sciences: a belief that only such methods can be fruitfully used in the pursuit of knowledge.” (p. 123)

C. S. Lewis wasn’t opposed to science, in fact his view seems to be to let the facts be the facts, and this included evolution, but scientific reductionism (scientism) is a real problem. His surviving BBC broadcast acknowledges both evolution and the problems with scientism. In particular humans are not simply the product of evolution – the nature of humans as new men in Christ goes beyond evolution. Start at 8 minutes for the relevant part for this post.

The self you were really intended to be is something that lives not from nature, but from God. (11:58-12:06)

Fritz quotes a reply by Lewis to Professor Haldane’s criticism of his space trilogy. In this reply, found in Of Other Worlds, (p. 76-77), Lewis defines scientism as “a certain outlook on the world which is usually connected with the popularization of the sciences, though it is much less common among real scientists than their readers. It is, in a word, the belief that the supreme moral end is the perpetuation of our own species, and this is to be pursued eve if, in the process of being fitted for survival, our species has to be stripped of all those things for which we value it – of pity, of happiness, and of freedom.” In an age colored by eugenics and the final solution of Hitler’s Germany, such a fear was not unfounded. Science was connected with social Darwinism, and this could be brutal. Eugenics was quite popular in the US and the UK prior to World War II. William Jennings Bryan’s objections to evolution in the 1920’s had much the same foundation.

Scientism today doesn’t take quite the same approach, but the reduction of humans to nothing but chemical reactions and such remains a threat. Fritz cites several examples in the this chapter, including an article in the International Journal of Quantum Chemistry (his specialty) where an author states “Living systems are wonderfully well-suited to their purpose, but the design is shaped by blind evolution instead of imaginative intelligence.” (p. 133) Another article I’ve found telling is the inaugural article in PNAS by Anthony Cashmore who wrote concerning humans “The reality is, not only do we have no more free will than a fly or a bacterium, in actuality we have no more free will than a bowl of sugar. The laws of nature are uniform throughout, and these laws do not accommodate the concept of free will.” Humans are nothing special in the grand scheme of things. Fritz comments “The reductionist has no definitive basis for his or her decision to greet or eat a stranger. Such a a worldview should be resisted, as Lewis did so well. I know, as surely as I accept Coulomb’s Law (like charges repel; opposite charges attract), that love is better than hate, and that the truth is better than a lie.” (p. 135) Although not as blatant as eugenics and the creation of a master race, there are significant questions in our culture today. The view that an embryo is nothing but bags of chemicals may be a threat. The idea that a fetus is not “human” before birth is a larger threat. Many such questions can be posed. When does humanity begin? Are less than genetically perfect humans of value? How much value? Is a life with Down’s syndrome worth living?

It is important to realize that the problems raised by scientism are not really scientific problems, the solution isn’t to fight the science. The problem is social, grounded in human failings. Fritz concludes the chapter (and his lecture) “My challenge to those of you who are not familiar with C. S. Lewis’s writings is to read his classic Mere Christianity and consider the claims of Jesus.” (p. 136)

Science and Christian faith need not be at odds – many active scientists (a theme running through a number of the essays and lectures in Conflict or Coherence) find the two coherent rather than in conflict.

Who has been particularly influential in your life and faith?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.