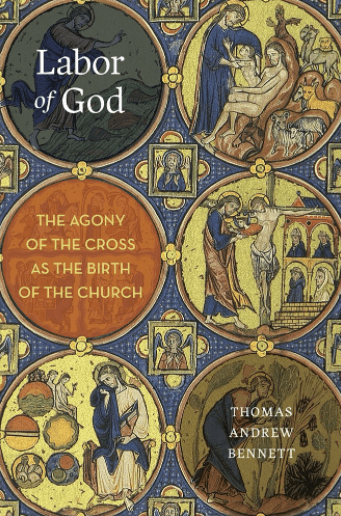

Yes, that’s the claim by Thomas Andrew Bennett, Labor of God: The Agony of the Cross as the Birth of the Church. At the heart of all atonement theories is a problem — a theodicy, sin, need for salvation, guilt, estrangement — and each atonement theory resolves that problem.

Yes, that’s the claim by Thomas Andrew Bennett, Labor of God: The Agony of the Cross as the Birth of the Church. At the heart of all atonement theories is a problem — a theodicy, sin, need for salvation, guilt, estrangement — and each atonement theory resolves that problem.

Bennett contends forcefully, though not too boldly or over-confidently, that previous models are insufficient. Here’s how he states it, and one of his major themes is that most theories are conglomerations of metaphors and systems of thought:

In order to make penal substitution work conceptually—so that it does not appear as absurd as our story about the child executed in a murderers stead—Christian doctrine conflates the narrative of penal substitution with the practice of sacrifice. … What is doubly strange about this intertwining—leaving aside its bizarre entangling of separate systems found in the Old Testament—is that it egregiously lets the condemned get away with murder, offers no account of whether the child’s sacrifice will change the criminal’s character in any way, and puts an innocent to death for no reason at all.

In “offers no account of whether the child’s sacrifice will change the criminal’s character in any way” Bennett makes a major claim: that an atonement theory must be and account for the personal transformation of the one who benefits from the atonement. Still, he thinks the combination of ideas makes no sense:

The logic of sacrifice rescues the logic of penal substitution from collapsing in on itself but has the unfortunate corollary of creating a bizarre, piecemeal metaphorical universe, one that bears little resemblance to the biblical worlds from which it has been fashioned.

The objective approaches are systems of exchange:

This for that, him for us, they present the death of Jesus as “for us” in the sense that his life buys ours, or he is taken hostage that we might be released, or he endures punishment meant for us, or he satisfies God’s honor or justice or righteousness on our behalf.

He disputes subjective models too, though he gives them scant attention — I agree that subjective accounts are not acts that accomplish something:

Unfortunately, models that explicitly eschew economies of exchange—that is, subjective accounts—have a hard time making sense of the cross.

Atonement as a coherent doctrine appears to be on the horns: either it is objective, and therefore involved in an economy of exchange that deconstructs conceptually, or it is subjective, and God does not act through the cross except to inform and inspire.

He proposes — by now clear to all readers of this blog series — “labor of God” as his model.

as the God-born, the spiritual children birthed at the cross possess a divine nature and the potential and propensity to live and act as God lives and acts. Moreover, as children embedded into the divine family that constitutes the church, the God-born are formed and nurtured in such a way as to bring this potential to its fruition. By all accounts, the cross as the labor of God generates an objective model of atonement m which real, God-authored change takes place in people.

Where to begin? We can all agree on this: atonement is a gift.

What is gift? This has been a very intense conversation for a century, beginning with Nietzsche and then on into Derrida and then to Ricoeur. The problem they bring to the table is that when gift is turned into obligation and reciprocity, gift is no longer gift but instead a kind of exchange. When it is exchange it is not gift. Bennett:

What is wanted, then, is an account of Scripture that does justice to the language of giftedness while nevertheless testifying to a model of atonement that is not mired in an economy of exchange.

[So he contends gift is transformed out of exchange when it is God’s gift.] That is, giftedness, if as a concept it truly describes something that has happened between God and human beings in and through the cross, will see its meaning altered in accordance with the weight of glory, as it were.

Here he becomes bold in criticism of ruling models of atonement:

Atonement theology has, therefore, made a tremendous category mistake. By applying a credit/debt notion of giftedness to the cross and invoking economies of exchange in order to explain what Jesus’ death did, our objective atonement models commit two equally egregious sins. Firstly, they fail exegetically, treating Pauls language of the gift as though he were speaking of an exchange among friends and not the terrible majesty of a crucified God. … Secondly, atonement theology’s models have inscribed an eternal recurrence—to plunder Nietzsche’s rhetoric—of debt into a transhistorical event that was meant to break indebtedness once and for all.

In other words, if it is a gift, it must be a gift and not something from an economy of exchange. He appeals to Wright’s translation of Romans 5:17 where the emphasis is grace/gift, covenant, and an economy of life. Here is Bennett’s summary conclusion: “rod, in Christ at the cross, has remedied the widespread disorder of sin. Creation, individual hearts, infected systems—all that are part and parcel of the covenant community have been rescued, fixed, healed, from the inside out” (85). The ringer: “This is the “free gift’ of Romans 5. It is not, the reader will also notice, an exchange” (85).

God is not “granting justification” or “inspiring sanctification” so much as beginning the end of a world dominated by just these sorts of mundane, pedestrian, and wholly powers-owned economic practices. Rather than a pardon or a mercy—however extensive such pronouncements may be—the gift of the cross is better understood as a new creation, a cosmological event instantiated in what theologians call ecclesiology. A new people, the God-born, gathered in a new family, the church, established as a landmark, a monument, signifying to the economies of the powers that another economy entirely already rules in the highest heavens and will one day do so always and everywhere. This is the divine “gift, and it is unserved by atonement models that denigrate it, reducing it to the tit-for-tat of favors asked and granted and returned. This is, of course, why ecclesiology must be sourced in labor and atonement, in the notion that the church is, fundamentally, the family of God, sharing God’s character and proclivities by birth, rather than as something extrinsic to nature. The family inculcates and nurtures and reinforces a way of being-in-the-world that is mostly unrecognizable to the world, saturated as it is by what we may now deem the disease of reciprocity (86).

Those are not necessarily false dichotomies but he will need to explain the other side of the negation and not just the affirmation on the near side. He will have to explain Why death? Why labor? Not just What is the purpose but What is the cause of all this work of grace?

What is needed is for the machine of exchange itself to be sabotaged, and sabotaged in such a way as to eliminate the very problems the machine was invented to solve. In this case, namely, the problem is sin in all of its distorting, corrupting, ruining ignominy. If only there were something, some kind of gift-that-was-not-a-gift, a way out of exchange altogether, something that defenestrated sin and exposed it and transformed people from what they are into what they ought to be. As we gaze at the labor of God, birthing spiritual children out of the cycles of exchange, perhaps we can cry out with Paul in Romans 7:24-25 (NRSV), “Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!’

One more chapter to read, but one question I’m not asking is if Bennett’s proposal does not need to interact with John Barclay’s understanding of gift/grace.