I’ve been reading Tom McLeish’s fascinating book Faith & Wisdom in Science – and, of course, reflecting on it here. Our first dip into the book looked at the clamor of voices proclaiming the conflict between science and faith (Faith in Science). The next chapter looks at the development and practice of science through the ages. Although it is common to think of science as a modern development, this is not quite accurate. Tom, a scientist and a Christian has become very much interested in the history of science. In fact, he has a new book we will dig into down the road, Let There Be Science: Why God Loves Science, and Science Needs God that explores this and related questions in more detail.

I’ve been reading Tom McLeish’s fascinating book Faith & Wisdom in Science – and, of course, reflecting on it here. Our first dip into the book looked at the clamor of voices proclaiming the conflict between science and faith (Faith in Science). The next chapter looks at the development and practice of science through the ages. Although it is common to think of science as a modern development, this is not quite accurate. Tom, a scientist and a Christian has become very much interested in the history of science. In fact, he has a new book we will dig into down the road, Let There Be Science: Why God Loves Science, and Science Needs God that explores this and related questions in more detail.

What is in a name? Science as a name is of recent origin. This was probably coined in the early 1800’s, around 1830. Prior to this science would be thought of as natural philosophy. Tom tells us “that ‘science’ and ‘scientist’ have Latin origins in the verb scio – ‘I know’.” (p. 25) Science is a claim to knowledge. Philosophy, on the other hand, has its roots in Greek – philia and sophia, love and wisdom. Natural philosophy conveys a notion of love for wisdom concerning nature.

Ask yourself: what happens to our image of science if we replace in our minds its word -label ‘I know‘ with ‘I love wisdom to do with natural things‘? Instead of a triumphal knowledge-claim we have a humbler search, together with more than a hint of delight. We also have as a goal something deeper than pure knowledge, in the wisdom that surrounds and supports it. (p. 25)

A love of natural things, a sense of wonder, awe, and discovery, even a search for wisdom is a current force in much of science today, and has been the driving force behind investigations for thousands of years. Tom looks at an example from his own work and then at several historical examples preceding the dawn of ‘science‘ or at least the origin of the term. In modern science we have teams, and a broader network of people “working together on winning a little more ‘wisdom of natural things’” and also “creating a community, trusting and appreciating each other’s contribution, supporting each other through difficulties and sharing a common belief in the value of our common goal.” Tom isn’t naive, scientists are human like everyone else. There are personalities and ambitions that also enter the picture. But just as it is wrong to view the church as dominated by quests for power and control (as outsiders are sometimes quick to do), so too it is wrong to view science as dominated by ambition and a quest for power and personal gain. There is something bigger and more noble in the reality.

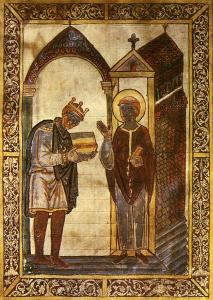

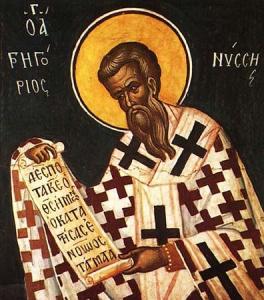

Stepping back in time, Tom looks at Robert Brown (early 1800’s) who first described what we now call Brownian motion (Einstein finally offered an explanation for the phenomenon in 1905), Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln (1200’s) who used observation to describe light and matter reasonably accurately given his context, The Venerable Bede (700’s) who wrote two short documents De Natura Rerum (On the Nature of Things) and De Temporibus (On Times), and Gregory of Nyssa (300’s, On the Soul and Resurrection). Despite our modern preconceptions and prejudices, Tom points out that all of these people relied on observation and reason to explore and describe the natural world.

Concerning Grosseteste, Tom notes:

Concerning Grosseteste, Tom notes:

Without requiring him to have formulated a way of doing science that would elicit nods from the founders of the Royal Society over three centuries later, he nonetheless is able to write of how the causes of a spreading infection can be determined by testing each possibility practically and observing the outcomes of the tests. As well as the cycles of living beings, he wrote about stars, the motion of the Earth, colour and sound. (p. 42-43)

Grosseteste also had quite interesting ideas about the nature of matter and of light as the means by which space is filled between point particles (atoms). Lucretius had introduced the concept of “atoms,” although not really our modern atom, long before (ca. 40’s or 50’s BC).

Bede certainly believed in miracles and the intervention of God in the world, but this doesn’t mean that he thought the nature of the world (God’s creation) was beyond human reason.

Bede certainly believed in miracles and the intervention of God in the world, but this doesn’t mean that he thought the nature of the world (God’s creation) was beyond human reason.

Bede is fearless in taking on an ancient authority in the light of observation and reflective thought. … he values digging below the surface of phenomena, has some idea of what might constitute ‘explanation’ of natural phenomena, and furthermore sees this entire process as central to learning as a natural part of being human and of his own vocation. …

… For Bede, his task as a Christian teacher and pastor is to seek explanation of nature on its own terms. He sees this achieving two things – it refutes superstition (of a natural world full of spirits and dark menace) and engenders an appreciation of wonder. (p. 48-49)

Gregory of Nyssa wrote of a conversation with his sister Macrina at her bedside during her last days. Macrina’s crowning evidence for the existence of the soul comes from her observations of water – and that a jar thought to be empty must really be filled with an unseen something. An ’empty’ jar floats before it fills and sinks. When it sinks bubbles and gurgles. This was also her crowning argument because “only minds may peer beneath the surface of matter and perceive there what is unseen by the eye alone.” (p. 51) She also uses the example of a spherical moon – we can understand the waxing and waning of the moon, but only be reason (at least in her day and age) not by direct observation.

Gregory of Nyssa wrote of a conversation with his sister Macrina at her bedside during her last days. Macrina’s crowning evidence for the existence of the soul comes from her observations of water – and that a jar thought to be empty must really be filled with an unseen something. An ’empty’ jar floats before it fills and sinks. When it sinks bubbles and gurgles. This was also her crowning argument because “only minds may peer beneath the surface of matter and perceive there what is unseen by the eye alone.” (p. 51) She also uses the example of a spherical moon – we can understand the waxing and waning of the moon, but only be reason (at least in her day and age) not by direct observation.

Macrina and Gregory throw a new light on our search for meaning to ‘faith and wisdom in science’. Recall that Macrina’s argument is working on two levels: she wants to display the eternal character of our minds by showing that they sit above material phenomena, but she is also conducting the whole debate to help Gregory cope with their shared pain, and to prepare him for their parting. Her faith is that this contemplation of wisdom about the natural world will play a part in the healing of her brother’s pain. … Macrina and Gregory embrace a Christian thought-world completely at ease with the material universe and its exploration. Natural philosophy is part of the theological story that they are not only telling, but living. (p. 52)

Of course, it is possible to find many more examples. We all know some of them from 1400 to 1800 including Galileo, Copernicus, Kepler and Newton. We also could look back further to the ancient Greeks and Romans. We’ve mentioned Lucretius above, but could also bring in Aristotle along with a number of others.

Tying it together. Tom Macleish draws five conclusions from his study of science and natural philosophy through the ages.

Tying it together. Tom Macleish draws five conclusions from his study of science and natural philosophy through the ages.

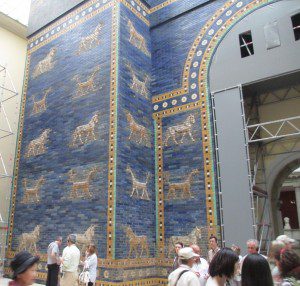

- Doing science is very old. Using human reason and logic to understand the natural world has a long history. It stretches back to the ancient Greeks and even before. This summer we learned of a Babylonian tablet that pushes the origin of math and trigonometry to ca. 1700 BC (see here for example: Mathematical mystery of ancient Babylonian clay tablet solved.) A modern shortcoming is that we fail to recognize fundamental signals that people are doing ‘natural philosophy’ or ‘science’. “We also commonly fall into the trap of forgetting the long history of imaginative science which constitutes the heritage on which we build.” (p. 51-52)

- Science is a deeply human activity. It isn’t the sole purview of the professional ‘scientist’ – although there are better and worse ways to go about it. Wonder about the world is part of what makes us human.

- Science is about asking questions. As Tom puts it: “Science is more about imaginative and creative questions than it is about method, logic, or answers to those questions.” (p. 53) Answers to the questions may come much later, when a proposed experiment becomes possible or through the collective effort and wisdom of many people.

- Science can be painful. There are ups an downs, episodes of elation and discovery as well as episodes of disappointment and dismay.

- The relationship between ‘faith’ in all its connotations and ‘science’ is a long and rich one. The idea that Science and Faith are in unavoidable conflict is of recent origin. It isn’t just religious faith and theology – Faith in ideas and reason is also essential. For many early European thinkers faith in God was inseparable from their faith in natural philosophy (science).

Natural philosophy is worth pursuing yet today. It can be a valid and powerful Christian calling as well as a secular pursuit. Science isn’t an enemy to faith, whatever the pundit might claim.

Have you thought about the origins of science?

When did ‘real’ science begin?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.