In his recent book Science and Christianity: An Introduction to the Issues, Jim Stump has a nice discussion of the role of interpretation in our approach to the Bible. Sola Scriptura is a foundation stone of the Reformation. Luther insisted on this in his dispute with the Catholic Church. If the church is corrupt and self-serving, as Luther and the other reformers believed (and there is certainly evidence to back up the claim at least in part) there has to be some other reliable foundation for understanding Christian faith. This foundation is found in the Bible. Stump focuses on the major problem with this approach: “But then this doctrine which began as a unifying cry against the institution very quickly became ground for endless divisions. Luther’s reading of Scripture was questioned by Zwingli and Calvin; theirs was questioned by the Anabaptists. And so on.” (p. 57) The interpretation of Scripture is not always obvious. In this post I will consider a few of the points brought up in the book.

In his recent book Science and Christianity: An Introduction to the Issues, Jim Stump has a nice discussion of the role of interpretation in our approach to the Bible. Sola Scriptura is a foundation stone of the Reformation. Luther insisted on this in his dispute with the Catholic Church. If the church is corrupt and self-serving, as Luther and the other reformers believed (and there is certainly evidence to back up the claim at least in part) there has to be some other reliable foundation for understanding Christian faith. This foundation is found in the Bible. Stump focuses on the major problem with this approach: “But then this doctrine which began as a unifying cry against the institution very quickly became ground for endless divisions. Luther’s reading of Scripture was questioned by Zwingli and Calvin; theirs was questioned by the Anabaptists. And so on.” (p. 57) The interpretation of Scripture is not always obvious. In this post I will consider a few of the points brought up in the book.

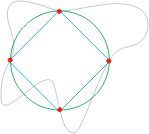

First, the data are sparse. The data in science or theology, “almost always underdetermines the theories that explain it.” In science theories are put to the test whenever new data rolls in. Of course, this doesn’t prevent enthusiasts from trying to squeeze the data into a favored mold … at least until the difference is overwhelming. The same can be true in theology as well. Jim has a nice example of four data points that can be fit to a circle, a diamond, or any of an infinite number of other shapes. I’ll adapt his illustration – but modify it a little.

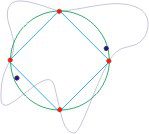

If two new data points are added there is a decision to make – one that depends on the way in which we interpret the data.

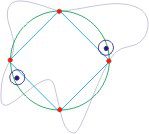

The blue points above could be viewed as supporting the circle interpretation. But other interpretations are possible as well. If we consider the points as “absolutes” we would draw a new shape, perhaps a slightly distorted circle, to pass through the red and blue points. Alternatively we might assign an error estimate to the blue points – or give them an interpretive shape.

In this situation the circle theorists may claim victory – but the diamond theorist will be satisfied that a diamond is still a good interpretation.

Inspiration. In a similar manner, we as Christian often take the statements in the Bible as data and fit them to theories that make sense of the data. Of course, in this method there is also another theory at work – a theory concerning the nature of the Bible and the mechanism of inspiration. Jim outlines two broad theories of inspiration acknowledging that there are many possible variations.

Inspiration. In a similar manner, we as Christian often take the statements in the Bible as data and fit them to theories that make sense of the data. Of course, in this method there is also another theory at work – a theory concerning the nature of the Bible and the mechanism of inspiration. Jim outlines two broad theories of inspiration acknowledging that there are many possible variations.

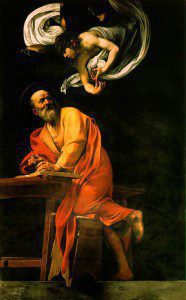

First: “the Bible , down to the details of its words, consists of and is identical with God’s very own words written inerrantly in human language. The dictation method is one way this might have happened; or perhaps God inaudibly “dictated” in the sense that the human author was not aware of the fact that God was using him, but God nonetheless causes each word to be written exactly as God desired.” (p. 64)

Or alternatively, “there was a special act of revelation to which the writings bear witness. For the Gospels, that revelation was the person of Jesus Christ who became human and dwelt among some people in 1st century Palestine. … We might say that God guided (i.e. inspired) their thoughts, but it was human beings who wrote the words.” (p. 64)

In light of our theory of inspiration we then turn to Scripture. Jim takes the Easter morning narratives as an example (I quote his summary on p. 65).

- Matthew: Mary Magdalen and the other Mary went to the tomb; when they got there, an angel appeared and rolled back the stone and sat on it. They left the tomb and met Jesus, who told them to tell his brothers to go to Galilee, where they would see him.

- Mark: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome went to the tomb; the stone had already been rolled away by the time they got there. They went into the tomb and there saw an angel, who told them to tell the disciples to go to Galilee, where they would see Jesus.

- Luke: Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women went to the tomb; the stone was already rolled away and they entered the tomb. There two men stood beside them; they went and told the disciples and Peter ran to the tomb to inspect it.

- John: Mary Magdalene went to the tomb alone and found that the stone had been removed; she went back to tell Peter and John, who ran to the tomb. After they left, Mary saw two angels in the tomb, and Jesus appeared to her. Then Mary went and told the disciples.

What do these examples teach us about the nature of inspiration? They all bear faithful witness to the resurrection, but it is hard to reconcile them with a dictation model of inspiration. Of course, we could draw an elaborate shape through the dots to reconcile the details. Perhaps Mary went to the tomb several times and each Gospel relates a part of the story. It seems a little farfetched, however, to suggest that God dictated a different scenario to each author. What are the important dots here and how should we connect them? What theory of inspiration and or the nature of Scripture best accounts for the data?

Science and the Bible. Our theory of the nature of Scripture and the mode of inspiration will play a significant role in our view of the interaction of science and Christian faith. Whether we like it or not science has shaped our interpretation of Scripture.

Science and the Bible. Our theory of the nature of Scripture and the mode of inspiration will play a significant role in our view of the interaction of science and Christian faith. Whether we like it or not science has shaped our interpretation of Scripture.

Here is the point most relevant for the Bible’s interaction with science. Instead of attempting to mine Scripture for scientific insights, we ought to allow for an ongoing conversation between what we learn about the created order and what we find in Scripture. Some Christians get nervous when we talk of allowing science to influence our interpretation of Scripture, but there is no denying that it has done so. The obvious allusions in the Bible to the movement of the sun were once interpreted literally, but no longer are, because of science. (p. 66)

There are at least a few different ways we can allow science to influence our reading of Scripture. The knowledge we gain from the study of God’s creation can help us identify culture bound language in Scripture and correct the error of taking it as an absolute. Another way would be to acknowledge that the Bible is to be interpreted anew by each succeeding generation. Jim quotes N.T. Wright who says:

The Bible seems designed to challenge and provoke each new generation to do its own fresh business, to struggle and wrestle with the text … Each generation must do its own fresh historically grounded reading, because each generation needs to grow up, not simply to look up the right answers and remain in an infantile condition. (Surprised by Scripture, p. 29-30)

Wright, of course, does not think that all interpretations are equally good – but simply that we must all dig in and think through the text.

What is your view of the nature of Scripture and the method of inspiration?

How does this influence your interpretation of Scripture?

Can a conversation between Scripture and experience (including science) help us to find fresh meanings of Scripture in light of what we know about the world?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.