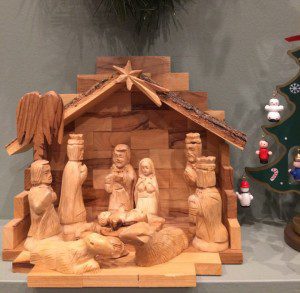

Advent, followed by Christmas is a season of anticipation and hope. Israel’s hope for the coming Messiah culminates in the birth of Jesus, the Messiah or Christ. It is fitting in this season to consider the importance of hope in human experience. Tim Keller in Making Sense of God devotes a chapter to hope … a hope that can face anything.

Advent, followed by Christmas is a season of anticipation and hope. Israel’s hope for the coming Messiah culminates in the birth of Jesus, the Messiah or Christ. It is fitting in this season to consider the importance of hope in human experience. Tim Keller in Making Sense of God devotes a chapter to hope … a hope that can face anything.

Christian hope in the resurrection and in the age to come is sometimes criticized as a drug to make the masses docile and submissive, willing to suffer for the present. Citing Howard Thurman, Keller points to the African American experience in slavery in the US as a counter to this view. The hope expressed in spirituals gave dignity and “served to deepen the slave’s capacity for endurance.” This because it included a hope for “a day on which all wrongs would be made right” (p. 158) as well as a hope for immortality and reunion. This hope was not only a future assurance, but a motivation to seek justice in this world. An annihilationist view – that we are nothing but matter, that this world is all there is and then we return to dust – provides no ground for hope or reason to endure.

Keller argues that hope is the glue that gives meaning to human existence. Without hope there is no reason to persevere when the going gets tough. Religion need not be the only focus for hope. Keller points out that the good of a community – the nation for example – can provide the necessary hope. But even this is lacking in modern society.

In our current phase of American history we have lost belief in God and salvation, or in any shared sense of national greatness and destiny. We do not see serving God or the nation as being more important than self-actualization. We do not consider the claims of religion or national loyalty to overrule our pursuit of individual freedom and happiness. Our hope now is for individual freedom to pursue our own ideas of good and to discover our authentic selves. (p. 159)

This is a poor foundation for any real hope. It has no answer for the certainty of death, or endurance in the face of persecution and oppression. There is no guarantee of justice in this world, even down the road for future generations, and no hope for divine justice on any level. The narrative that death is simply part of life – a never ending circle – provides little consolation in the light of broken relationships. No one really finds peace in the thought of their loved one as fertilizer for the next generation of flowers.

Above all, the things that make life meaningful are love relationships. Death removes them one at a time over the years, stripping you down and down. Finally, it comes for you and removes you from the loved ones remaining. Almost by definition, real love wants to last; it never wants to part from those we love. Death strips us of everything that makes life meaningful – so how can it be nothing to fear? (p. 163)

Personal. Keller argues that the Christian hope is personal – it preserves persons and the love relationships between persons. This personal hope gives us the anticipation of perfected love in the age to come. Human failings and self-centered focus make love a sometimes painful experience, but even this will be put right in the age to come. “If we are not a self after death, then we have lost everything, because what we most want in life is love.” (p. 167)

Personal. Keller argues that the Christian hope is personal – it preserves persons and the love relationships between persons. This personal hope gives us the anticipation of perfected love in the age to come. Human failings and self-centered focus make love a sometimes painful experience, but even this will be put right in the age to come. “If we are not a self after death, then we have lost everything, because what we most want in life is love.” (p. 167)

This personal hope runs counter to Eastern religions and to some liberal Christian theology. A few years back I read a book by John Haught, Making Sense of Evolution. In his chapter on Death he comments: “To Christian theologians, the challenge after Darwin is to think of the universe as a place of promise and purpose in spite of the fact that everything in the life-story – and eventually the universe itself fades into oblivion.” (Haught p. 102) He interacts with several theologians, including Paul Tillich and Alfred North Whitehead, leading to the suggestion that our immortality comes from our stories “preserved forever in God’s saving memory.” (Haught p. 107) Our material existence comes to an end, but what we have done and who we are lives on for eternity in the life of God. This wisp of hope is not Keller’s vision, nor is it the Christian hope of orthodox theology for resurrection and the Kingdom of God. Added: Haught himself does not deny subjective immortality of persons, noting: “Our hope for conscious, subjective survival of death makes very good sense if the universe and evolution have an everlasting importance to God.” (Haught p. 105)

Concrete. The promise is not “an immaterial, spiritual paradise” as often expressed in popular imagination nor an existence in “God’s saving memory” as suggested above. The hope is concrete and the promise is for justice and existence. “At the end of history, described in images that overflow and swamp all our categories, we do not ascend to heaven, but God’s heavenly glory and purifying beauty and power descend to renew this material world, so that evil and suffering, aging, disease, poverty, injustice, and pain are removed forever (Revelation 21:1-5, 22:1-4) Christians do not merely look forward to the redemption of their souls but also of their bodies (Romans 8:23).” (p. 171)

Assured. Falling back on a theme in much of his work, Keller concludes the chapter with the idea that Christian hope is not based on being found worthy in the judgment based on “a morally good and religiously observant life.” (p. 174) Our assurance is based on the saving work of Christ and on our faith in him. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, the Christ, is the foundation of our hope. “One ground of our assurance is the Resurrection of Christ himself, the historical evidence for which is formidable, as demonstrated by such scholars as Wolfhart Pannenberg [Systematic Theology p. 343-363], N.T. Wright [The Resurrection of the Son of God], and others.” (p. 175) As Paul wrote to the church in Corinth, if Christ has not been raised our preaching is useless and so is your faith.

Our assurance comes from the reality of the resurrection of the son of God. Our hope begins with his birth.

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the greatness of his government and peace there will be no end. He will reign on David’s throne and over his kingdom, establishing and upholding it with justice and righteousness from that time on and forever. The zeal of the Lord Almighty will accomplish this. (Is. 9:6-7)

Is hope the glue that provides meaning for human existence?

What is our hope? How can this hope be explained or defended?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.