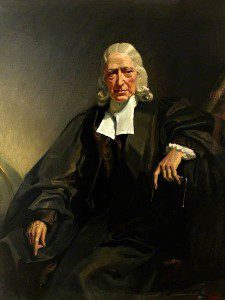

The final section of Matthew Nelson Hill’s new book Evolution and Holiness looks at John Wesley’s view of original sin and human nature and the interaction between the structures he put in place with small accountability groups and more modern ideas from sociobiology. I was raised in a Baptist church, with something of a “soft” Calvinist bent. (TULIP appalled me when I first heard of it in college – it was not explicitly or implicitly taught.) I have attended Presbyterian or Baptist churches all of my life. As a result some of these aspects of Wesley’s thought were new to me. (My Baptist upbringing and college taught me precious little about Lutheranism and nothing at all about Weslyanism, except that “we” were not like “them.”)

The final section of Matthew Nelson Hill’s new book Evolution and Holiness looks at John Wesley’s view of original sin and human nature and the interaction between the structures he put in place with small accountability groups and more modern ideas from sociobiology. I was raised in a Baptist church, with something of a “soft” Calvinist bent. (TULIP appalled me when I first heard of it in college – it was not explicitly or implicitly taught.) I have attended Presbyterian or Baptist churches all of my life. As a result some of these aspects of Wesley’s thought were new to me. (My Baptist upbringing and college taught me precious little about Lutheranism and nothing at all about Weslyanism, except that “we” were not like “them.”)

A key component of early Methodism was the creation of structures, small groups, designed for accountability to help to shape the serious Christian in what Wesley termed “Christian perfection.” Hill’s interest is in the way these accountability structures encourage virtues that might be considered “unnatural,” such virtues as altruism and generosity.

First, Wesley’s views:

Wesley did not see human nature in a positive light; yet he continually saw God working with individuals to help correct their natural tendencies. (p. 139)

All persons are not completely bent toward depravity because all persons are recipients of prevenient grace. (p. 140)

For those of us not schooled in theology, prevenient is from the Latin meaning coming before, antecedent or anticipatory. This is a grace that anticipates (and enables) conversion and sanctification.

For Wesley, Christian perfection always consisted of wholly loving God with one’s heart, soul, mind and strength, and loving one’s neighbor as oneself. (p. 140)

Christian perfection isn’t a final state, for is is possible to fall back into the ways of the world, but it is, in Wesley’s view, an achievable goal that should be sought in this life. It is also not achieved through human effort alone, but requires the grace and Spirit of God.

Wesley also focused on the whole person and thus sidestepped dualism that separated body and soul. Hill notes that he spoke and wrote using the language of his day and age – embodied souls or spirits, but he also had a holistic view of the human person. This shaped his approach to sanctification or Christian perfection.

Sanctification or “Christian perfection” is not an internal state but manifest in all aspects of life.

For Wesley, part of being truthful to the biblical understanding of perfection was recognizing the connection between Christian perfection and what he called “social holiness,” where inward holiness resulted in outward action. (p. 154)

We cannot separate loving God with heart, mind, soul, and strength from active and purposeful love of neighbor.

Wesley held original sin to be real, and depravity a disease of the human condition. Humans are constrained by the flesh, its histories and weakness. But these can be overcome.

Is God the causal agent in human Christian perfection or does human action play a central role? The answer may be similar to that which Paul proposes in Philippians 2:12-13, where he encourages those at the church in Philippi to “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; for it is God who is at work in you, enabling you both to will and to work for his good pleasure.” … Wesley’s commentary, called Notes of the New Testament, proves extremely revealing. In it he articulates that “not for any merit of yours. Yet his influences are not to supersede, but to encourage, our own efforts. Work out your own salvation – Here is our duty. For it is God that worketh in you – Here is our encouragement. And O, what a glorious encouragement, to have the arm of Omnipotence stretched out for our support and our succour!” According to Wesley, both God and humanity play a critical role in Christian perfection: God acting through grace and humans acting through volition of the will. (p. 165-166)

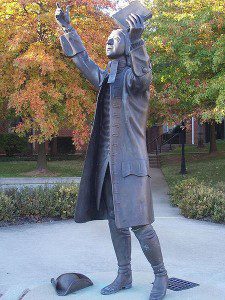

Second, Wesley’s structures: The Methodist societies. Structured groups of bands and classes met outside of regular Anglican services to provide accountability and discipleship. The bands, small groups of 5 to 10, and larger classes and societies, provided the structure necessary to encourage and enable change and spiritual growth in Christians … and enforce discipline.”The classes were effectively house churches, rather than “Sunday school” or other modes of more formal instruction. They met in homes of members and the leaders functioned as pastors.” (p. 182) The bands were smaller, more intimate groups. Accountability groups were viewed as essential for modification of behavior and progress toward Christian perfection and holiness. Christian faith is personal, but it is not isolated and inward.

Second, Wesley’s structures: The Methodist societies. Structured groups of bands and classes met outside of regular Anglican services to provide accountability and discipleship. The bands, small groups of 5 to 10, and larger classes and societies, provided the structure necessary to encourage and enable change and spiritual growth in Christians … and enforce discipline.”The classes were effectively house churches, rather than “Sunday school” or other modes of more formal instruction. They met in homes of members and the leaders functioned as pastors.” (p. 182) The bands were smaller, more intimate groups. Accountability groups were viewed as essential for modification of behavior and progress toward Christian perfection and holiness. Christian faith is personal, but it is not isolated and inward.

Matthew Hill’s focus is on altruism and the way that these Methodist structures encouraged altruism. Because Christian perfection is social and outward, to love one’s neighbor as one’s self, Christian perfection must include altruistic ethics.

John Wesley created an environmental world of constraints that pushed people toward altruism. These constraints, which were the outcropping of his highly structured accountability groups, worked to suppress other biological tendencies that would have encouraged the individual to be more selfish. In a way, Wesley created an organized community that encourages underlying natural tendencies toward altruism. Wesley’s passion for a change in people’s lifestyle exuded in all that he did. With those who were ungenerous, he felt a strong need to encourage modifications in their behavior. One can easily track his encouragement in his sermons, especially those moments in which he employs fiery language when focusing on the seriousness of shifting one;s disposition toward altruism and Christian love. To those who seemed predisposed toward altruism , Wesley likewise encouraged through regular meetings, since accountability had proven to be necessary to maintain changed behavior. (p. 186)

Discipline in the bands and classes included rebuke and excommunication. This wasn’t a soft program, for true change requires serious effort. Hill points out that individuals were rarely expelled for failure to keep some religious ordinance, and “none were ever recorded as excommunicated for doctrinal differences.” (p. 188) Rather, most were removed for “lightness and carelessness” or “not taking seriously enough their religion.” Inward faith will be reflected in earnest attempts in outward actions. These outward actions will embody active love for others. Christian community is essential. Hill quotes from Wesley’s writings:

“Holy solitaries” is a phrase no more consistent with the gospel than holy adulterers. The gospel of Christ knows no religion, but social; no holiness but social holiness. “Faith working by love” is the length and breadth and depth and height of Christian perfection. “This commandment we have from Christ, that he who loves God, love his brother also;” and that we manifest our love “by doing good unto all men; especially them that are of the family of faith.” (p. 193)

Hill also includes an appendix with the directions given to band societies in 1744 (pp. 225-226). These include aspects of personal piety in attendance at holy services, regular prayer and the reading of and meditation on scripture and such rules as “neither to buy or sell anything on the Lord’s day,” and “to wear no needless ornaments, such as rings, earrings, necklaces, lace, ruffles” alongside social admonitions “not to mention the fault of any behind his back, and to stop those short that do,” and “to give alms of such things as you possess, and that to the uttermost of your power.” The bands and societies encouraged altruism, but also a strict kind of holiness that detours into legalism. On the other hand these structures do serve to shape and form people as Christians. (And such admonitions were not unique to Wesley and his followers of course.)

The success of Wesley’s movement rested in large part on his structures. These structures helped to confirm and established the new converts (revivalism was in the air) in their faith. Those who stayed were committed to serious change and a serious faith.

What can we learn from Wesley?

Do you agree that “the gospel of Christ knows no religion, but social; no holiness but social holiness?”

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.