Chapter 4 of Genesis begins on what should be a happy note, the birth of two sons, but things quickly go south.

Chapter 4 of Genesis begins on what should be a happy note, the birth of two sons, but things quickly go south.

Now the man knew his wife Eve, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have produced a man with the help of the Lord.” Next she bore his brother Abel. Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of his flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell. The Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is lurking at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it.” (v. 1-7)

Why did God reject Cain’s offering? Some attempt to compare the occupation of Cain and Abel and find the reason there. Or God desires a blood offering rather than some vegetable matter. Tremper Longman III (Genesis in the Story of God Bible Commentary), John Walton (The NIV Application Commentary Genesis), and Bill Arnold (Genesis (New Cambridge Bible Commentary)) all agree that this is a move in the wrong direction. The text does not institute such offerings as a religious ritual, it assumes the offerings as gifts to the one responsible for the bounty of their labor. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with a grain offering, especially as it represents the fruit of Cain’s labor. The most likely place is in the open generosity of the offering. Did Cain give willingly of his best or begrudgingly of that he wouldn’t miss? Walton notes that “Cain’s offering is not specifically criticized for its poor quality, but neither does the text specify that it is from the firstfruits.” (p. 263) Ultimately Walton is noncommittal, “the only thing the text makes clear is that Cain, in some way, does not do what [was] right.” (p. 263) Arnold comes to a similar conclusion, while Longman is more convinced that the problem lay in the willingness of Cain reflected in the quality of his gift. “Abel is enthusiastic in his worship, while Cain is basically disinterested.”

More significant is God’s warning to Cain. Sin is lurking at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it. Sin personified is a demon waiting to pounce on Cain. This demon desires to possess and rule over Cain. Arnold points out that the conclusion is key to the verse. Cain is free to submit to or resist the demon. “He is teetering on a precipice of disaster, and it is entirely up to him which way he turns. Cain is a free moral agent and must master his own impulses or suffer the same consequences as his parents.” (p. 79)

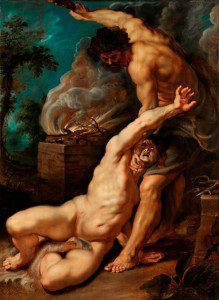

Cain doesn’t resist. Instead he gives in completely and commits a heinous act – the murder of his brother. Arnold continues:

That which began in the Garden of Eden continues in a more disturbing way among humans East of Eden. The transgression has become a premeditated, violent act – fratricide. Humans, having been given freedom and warnings about the consequences of their actions, nevertheless commit violent acts, which alienate God and violate each other. (p. 79)

Put bluntly, Cain falls. He then presumes his deed is hidden when God questions him. Both parallel to the events of Genesis 3. God, of course, knows his deed and confronts Cain. Surprisingly Cain is not executed for his crime. Like his parents Cain is expelled from his current home and from the presence of God. Life just got harder.

Cain said to the Lord, “My punishment is greater than I can bear! Today you have driven me away from the soil, and I shall be hidden from your face; I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and anyone who meets me may kill me.” v. 13-14

Arnold sees here an allusion to the Israelite custom where the “avenger of blood” was expected to exact vengeance. When Cain was forced out he would have no protection from any who desired to avenge Abel’s death. (There is no assumption in this story that Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel are the only humans around. Nor can other offspring of Adam and Eve account for this. As Seth was a replacement for Abel, born in Adam’s 130th year there wasn’t exactly time for a large population starting from two. This is, as Longman points out, “another signal that we should not take the text as a precise literal historical account.” (p. 89))

God cared for Adam and Eve after their fall, clothing them before banishing them from the garden. Likewise God shows grace to Cain giving protection from his enemies.

Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden. v. 15-16

The nature of the mark itself has been a subject of much speculation, but is of no significance. More significant is the response of God to Cain’s lament. As Arnold notes “But the point is that Yahweh has provided for Cain, even as he was evicted from “the [protective] presence of the Lord” and was forced to settle in the land of Nod (“Wandering,” “Homelessness”), still farther East of Eden.” (p. 80-81)

Bill Arnold titles this section of his commentary “Human Origins, Part 2.” While it is a continuation of the story from Genesis 3, it is also a second fall with many parallels to the first. Significantly, however, the temptation comes not from outside Cain (no serpent here) but from within. He (most likely) gives thanks to God for the bounty of his harvest only grudgingly. When his offering fails to find favor he is hurt. He can’t attack God, so he turns instead against his brother who found favor with God. The most significant parallels are in what follows. There are consequences for Cain’s act, but also mercy and grace. This is a theme that repeats. In the garden, with Cain, in the story of the flood, in the tower of Babel, and on through the story of Israel. This theme is, perhaps, the most important take-home message from the early chapters of Genesis. The rebellion of humans grows, sin is a demon lurking at the doorway. Punishment results, yet God remains involved with his people created in his image. Longman comments on this more extensively at the end of his section on Genesis 1-11 and we will return to the theme at the end of this section as well.

What is the point of the story of Cain?

What message should we take to heart?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.