One common argument brought up to cast doubt on the theory of evolution is the absence or paucity of intermediate or transitional forms. Much is made of the fact that there is no evidence for “macroevolution” – one kind becoming another completely different kind. But transitional forms … what does this mean? Presumably animals with traits characteristic of two different modern species – a crocoduck or a kangaroach. But wait, we do have such creatures in the platypus, the coqui, and the tarsier. All of these are in some sense “intermediate” between major groups of living animals. The problem is, to most people these don’t seem “transitional.” They are simply interesting animals.

One common argument brought up to cast doubt on the theory of evolution is the absence or paucity of intermediate or transitional forms. Much is made of the fact that there is no evidence for “macroevolution” – one kind becoming another completely different kind. But transitional forms … what does this mean? Presumably animals with traits characteristic of two different modern species – a crocoduck or a kangaroach. But wait, we do have such creatures in the platypus, the coqui, and the tarsier. All of these are in some sense “intermediate” between major groups of living animals. The problem is, to most people these don’t seem “transitional.” They are simply interesting animals.

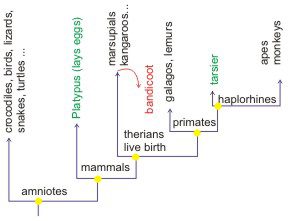

In chapter three of Evolution and Belief: Confessions of a Religious Paleontologist Robert Asher looks at evolutionary trees, intermediates, and transitional features concentrating on currently living species. He leads us to think hard about what is meant by intermediate or transitional forms in biology. Evolution is not inherently a purposeful progression from simple to complex. In the last post on the book I included the diagram to the right depicting the course of evolution over the last 6000 years or so. While it is common to think of evolution in terms of a tree or bush of life, the reality at any given time, or even over tens of thousands of years, is far more mundane. Excepting the occasional meteor hit or such, animals go about their ordinary life from generation to generation. Some extinctions, perhaps a little branching, but for the most part stability. And this leads to Asher’s first point.

In chapter three of Evolution and Belief: Confessions of a Religious Paleontologist Robert Asher looks at evolutionary trees, intermediates, and transitional features concentrating on currently living species. He leads us to think hard about what is meant by intermediate or transitional forms in biology. Evolution is not inherently a purposeful progression from simple to complex. In the last post on the book I included the diagram to the right depicting the course of evolution over the last 6000 years or so. While it is common to think of evolution in terms of a tree or bush of life, the reality at any given time, or even over tens of thousands of years, is far more mundane. Excepting the occasional meteor hit or such, animals go about their ordinary life from generation to generation. Some extinctions, perhaps a little branching, but for the most part stability. And this leads to Asher’s first point.

… animals are not really ever in “transition.” Living things are not trying to become something else. Apes from the early Miocene did not anticipate that some of their descendant would evolve into habitual bipeds. …

Terms such as “transition” and “intermediate” are useful because they convey the real sense in which both living and fossil animals mix anatomical and molecular attributes from various parts of the Tree of Life. (p. 47)

Many animals, even those that seem to us to perfectly “normal” exhibit what might be called transitional or intermediate features. Asher goes on:

However, the sense of active transformation as as commonly implied by those words in English is not really applicable in evolutionary biology. Hence these terms are best avoided, or when used applied to features of species, not to the species themselves. “Transition” evokes the image of a now entirely outdated notion popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of the “great chain of being” in which life shows “progress” (a term even worse than transition) from “sea creature into amphibian into reptile into rodent into primate into human.” This is a misguided sentiment … Evolution is not inherently progressive. (p. 47)

Asher reacts against the idea of progress, but it seems clear that there is indisputable evidence for “progress”. I don’t mean a great chain of being where life progresses from bacteria to fish to apes. Evolution is not like water flowing in a river from point A to B, say the Mississippi from Itasca to the Gulf of Mexico. Evolution is more like Lake Shasta filling all available space as the water level rises (image credit). The progress of evolution enables access to new areas in the feasibility space for biological life. From an evolutionary point of view humans exist because the progress of evolution made hands and eyes and larger brains possible. Whether there is a purpose to this progress is a metaphysical question. The naturalist might well conclude no, there is no purpose to evolutionary progress. As a theist I would disagree.

Asher reacts against the idea of progress, but it seems clear that there is indisputable evidence for “progress”. I don’t mean a great chain of being where life progresses from bacteria to fish to apes. Evolution is not like water flowing in a river from point A to B, say the Mississippi from Itasca to the Gulf of Mexico. Evolution is more like Lake Shasta filling all available space as the water level rises (image credit). The progress of evolution enables access to new areas in the feasibility space for biological life. From an evolutionary point of view humans exist because the progress of evolution made hands and eyes and larger brains possible. Whether there is a purpose to this progress is a metaphysical question. The naturalist might well conclude no, there is no purpose to evolutionary progress. As a theist I would disagree.

But beyond this introduction, the bulk of the chapter explores the nature of transitional or intermediate features found in a variety of animals alive today. Asher gets a little technical at times, but overall this is a good lay-level presentation.

The Platypus. The tree of life shown to the right is adapted from Figure 3.1 (p. 44) and illustrates the relationship between some of the species Asher discusses as “intermediate” or “transitional”. The platypus, for example, “lays eggs and has multiple bones in its shoulder skeleton (like a crocodile), but provides milk for its young, shows a single bone in its jaw, and has three ear bones (like a kangaroo).” (p. 45) The echidna is another less well known egg-laying mammal found in Australia and New Guinea.

The Platypus. The tree of life shown to the right is adapted from Figure 3.1 (p. 44) and illustrates the relationship between some of the species Asher discusses as “intermediate” or “transitional”. The platypus, for example, “lays eggs and has multiple bones in its shoulder skeleton (like a crocodile), but provides milk for its young, shows a single bone in its jaw, and has three ear bones (like a kangaroo).” (p. 45) The echidna is another less well known egg-laying mammal found in Australia and New Guinea.

Their long evolutionary past shows that neither echidna nor platypus is simply a throwback to some 160-million-year-old animal. However, it is equally clear that these animals mix anatomical features otherwise found in reptiles and mammals in just the way one would expect if Darwinian natural selection was the mechanism behind their evolution. (p. 54)

The platypus isn’t a transitional species along the line from amniotes to therians, but it evolved in a different direction from a common ancestor retaining intermediate features.

The bandicoot provides a different kind of example of evolution. Although it clearly belongs to the family of marsupials it possesses a placenta that is more like that of nonmarsupial mammals. Paraphrasing from Asher p. 56: All amniotes, animals not requiring direct access to standing water for reproduction, have four amniotic membranes. The amnion surrounds the embryo, the chorion lines the egg, the allantois stores water and waste and the yolk sac stores nutrients. Most marsupials have a placenta that combines chorion and yolk sac. In contrast placental mammals have a placenta that combines chorion and allantois. Bandicoots, unlike other marsupials, have a placenta that combines chorion and allantois like mice, apes, and other placental mammals. This feature of the placenta of the bandicoot illustrates the way that similar anatomical features can evolve independently. Asher gives some plausible explanations for why the combination of chorion and allantois doesn’t dominate in marsupials – but that is secondary to the main point. The bandicoot isn’t “intermediate” but rather an example of convergence in evolution.

The bandicoot provides a different kind of example of evolution. Although it clearly belongs to the family of marsupials it possesses a placenta that is more like that of nonmarsupial mammals. Paraphrasing from Asher p. 56: All amniotes, animals not requiring direct access to standing water for reproduction, have four amniotic membranes. The amnion surrounds the embryo, the chorion lines the egg, the allantois stores water and waste and the yolk sac stores nutrients. Most marsupials have a placenta that combines chorion and yolk sac. In contrast placental mammals have a placenta that combines chorion and allantois. Bandicoots, unlike other marsupials, have a placenta that combines chorion and allantois like mice, apes, and other placental mammals. This feature of the placenta of the bandicoot illustrates the way that similar anatomical features can evolve independently. Asher gives some plausible explanations for why the combination of chorion and allantois doesn’t dominate in marsupials – but that is secondary to the main point. The bandicoot isn’t “intermediate” but rather an example of convergence in evolution.

The Tarsiers. The tarsier is a small primate found today in the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi and Sumatra, but found in fossil forms over a far larger range. This small primate is characterized by a small nose and large eyes. Although it is not apparent from the picture, the tarsiers share a number of features with the lemurs and galagos despite being haplorhines, primates that possess small dry noses and are more visually oriented. In fact, the tarsiers, with their large eyes, are among the most visually oriented haplorhines.

The Tarsiers. The tarsier is a small primate found today in the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi and Sumatra, but found in fossil forms over a far larger range. This small primate is characterized by a small nose and large eyes. Although it is not apparent from the picture, the tarsiers share a number of features with the lemurs and galagos despite being haplorhines, primates that possess small dry noses and are more visually oriented. In fact, the tarsiers, with their large eyes, are among the most visually oriented haplorhines.

Tarsiers have a jaw structure consistent with the galagos and lemurs.For example …

the two halves of its jaw, loosely connected to one another in front, not solidly fused into a single, horseshoe-shaped bone as they are in an anthropoid. (p. 59)

But other features are more like the anthropoids (monkeys, apes, humans):

On the other hand, tarsiers resemble anthropoids in having a bony wall in the back of their orbit …, multiple enclosed spaces within their middle ear, a right angle defining the connection of its astralus to its fibula (comprising the ankle), and in not having the capacity to make their own ascorbic acid, or vitamin C. (p. 59)

The galagos and lemurs are capably of making vitamin C; there was an ancestor after the split that lost the ability.

And perhaps most interesting, like the anthropoids the tarsier lacks a tapetum, a reflective structure within the eyeball. The large eyes of this nocturnal creature compensate for the lack of the tapetum. The galagos has the tapetum and has a larger nose and smaller eyes, although also nocturnal occupying a similar ecological niche. The shiny eye in the picture of a galagos or bush baby to the left is a consequence of the tapetum. The “eyeshine” you see from a deer or raccoon caught in the headlights is also a result of the tapetum, which is common to many mammals.

And perhaps most interesting, like the anthropoids the tarsier lacks a tapetum, a reflective structure within the eyeball. The large eyes of this nocturnal creature compensate for the lack of the tapetum. The galagos has the tapetum and has a larger nose and smaller eyes, although also nocturnal occupying a similar ecological niche. The shiny eye in the picture of a galagos or bush baby to the left is a consequence of the tapetum. The “eyeshine” you see from a deer or raccoon caught in the headlights is also a result of the tapetum, which is common to many mammals.

To wrap it up. This is not an exhaustive list of all “transitional” or “intermediate” features observed among living creatures. It is only a very small selection of the cases that have been studied and documented. Some of the similarities and differences are only apparent when comparing bones, metabolism, or placental membranes. Others are only apparent when studying the DNA sequences themselves.

Asher summarizes:

Anti-evolutionists can complain that there are unsolved questions and uncertainties, and indeed a careful search of the literature will find qualifications to the generally accepted ideas concerning adaptation and evolutionary relationships that I’ve summarized above. This is the nature of any vibrant scientific field. Nevertheless, the reality is that the Darwinian process of natural selection is reasonable demonstrable as the major explanatory factor in all of the above cases. … Calling such an animal an act of “design” or “creation” simply repeats the fact that they exist. We knew that. No such claim does the hard work of specifying a mechanism by which their particular suite of characters came about in an individual, living species. (p. 62)

Asher misses part of the point here. The one who calls such an animal an act of design or creation is simply stating that God created each in largely the form they currently display. There is no reason to do harder work of specifying a mechanism. But the reason that evolutionary theory is the uncontested basis of all of modern biology is that it works to explain the broad sweep of life. It accounts for the intermediate forms that exist, for the hidden and apparently unnecessary features in many creatures, and for the variety of ways that different animals occupy their various niches. Evolution over long periods of time is not seriously disputed. That natural selection is the mechanism may need some refinement. Natural selection is unquestionably one of the major mechanisms resulting in biological diversity, but it need not be the only mechanism at play.

There is another important point here though. Evolution is not a red in tooth and claw survival of the fittest. As far as any individual animal is concerned, they simply live from day-to-day, and eventually die. The past was much like the present, with changes imperceptible to the average cat, fish, or dinosaur. Evolution works at the level of populations, and gradually populations differentiate and fill different niches in the biosphere. Even here the “intermediate” features can and do often persist to the present.

Do these creatures, for example the platypus and the tarsier, answer some of the questions about transitional and intermediate forms?

What do you expect from intermediate or transitional forms?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.