Pastoring is a hard job. No question about this. People are messy and pain and suffering are quite real. I don’t want to criticize. But there are some things I wish pastors knew about life as a scientist, or for that matter about life as an academic across a range of disciplines.

Pastoring is a hard job. No question about this. People are messy and pain and suffering are quite real. I don’t want to criticize. But there are some things I wish pastors knew about life as a scientist, or for that matter about life as an academic across a range of disciplines.

But first …

Scot recently linked a book I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship. Seeing Walter Moberly, whose book on Old Testament Theology I’ve slowly been working through, on the list of contributors I immediately ordered a copy. The back cover to the book poses the question: “Is serious academic study of the Bible a threat to faith?” and the contributors were asked to address a series of questions including “Have there been ways in which you felt your faith to be in jeopardy as a result of your study?” and “How might you address the question of “losing faith” through serious study of the Bible?“

Two of these chapters are worth a serious look today, Walter Moberly and Bruce Waltke.

Walter Moberly relates how, when preparing for ministry or perhaps to alternate between academic and ministerial positions, he contracted a chronic illness that decided the matter:

In Christian ministry you need an energy that I no longer have, an availability that I can no longer offer. The academic life is more structured and sedentary that Christian ministry, and I am also a private citizen at evenings and weekends, which are necessary recovery times. … [Eventually] I was able to accept my limitation as part of God’s good purpose for me. Alongside that acceptance came also a growing sense of vocation to be a theologian working with Scripture. (p. 204)

As I said, pastoral work is hard and deserves our support and respect. But there is more to Moberly’s story. Over the years he describes his professional life as “a continuing process of learning, trying to find categories and frames of reference that would help me genuinely unite head and heart, i.e. unite rigorous scholarly work with the priorities of faith in the study of the Bible.” (p. 206)

As an Old Testament scholar one significant challenge is the relationship between the text and reality, a challenge that confronted him early on.

The problem lay with material that has no clear indication of genre, whose genre must therefore be inferred. My initial assumption was that if a narrative were “history-like” then it should be considered “history.” (p. 206)

Many Christians today hold a similar position. It is a push-back that I have gotten repeatedly as I’ve explored interpretations of Genesis 1-11 and other passages of Scripture (Job and Jonah for example). Genesis 1 (creation) or 11 (the tower of Babel) is history-like prose and should therefore be taken at face value as history. Moberly grew to realize that this is an overly simplistic approach. In contemporary literature we often make judgements about genre for texts that are “history-like.” The stories carry meaning whatever the genre. He goes on:

Many Christians today hold a similar position. It is a push-back that I have gotten repeatedly as I’ve explored interpretations of Genesis 1-11 and other passages of Scripture (Job and Jonah for example). Genesis 1 (creation) or 11 (the tower of Babel) is history-like prose and should therefore be taken at face value as history. Moberly grew to realize that this is an overly simplistic approach. In contemporary literature we often make judgements about genre for texts that are “history-like.” The stories carry meaning whatever the genre. He goes on:

The oddity, or so it came to seem to me, is to combine a flexible understanding of the nature and purpose of genre in contemporary material with a rather inflexible understanding of the nature and purpose of genre in biblical material.

As I reflected on the fact that literature may validly portray reality through a variety of genres, I cam to ask myself: If a literary genre – say myth or legend – is widely attested in the pre-modern world and was meaningful to those who used it, why should it not be present in Scripture? Or more theologically, why should God not be able to make use of such meaningful genre as a part of inspired Scripture? (p. 207)

This doesn’t mean that texts are dismissed as myth or legend, but that effort can be redirected to carefully consider the genre of each passage and to focus on understanding the subject matter and the intended message. This has been the focus of Moberly’s career at Durham, a secular university where the ability to articulate the perspectives of faith in a manner that can be understood in this environment is necessary.

Among other things, this is perhaps a reminder to any would-be Christian scholar that we need to be prepared to let God lead and direct us as we wills, in ways that we may not expect and maybe will not initially welcome or comprehend. Probably the greatest challenge that any Christian scholar faces, however, is not different from that which any believer faces: How can I keep my first love fresh? Love for God and love for one’s subject can both become dulled over time. There is no simple solution. For me, at least, it is a matter of life-long learning: learning to bring together head and heart, learning to pursue both truth and goodness, and learning to recognize that any and every place and time and situation is where, in the words of Moses, I must choose life. (p. 210)

I am a Christian scholar. As I read this chapter by Moberly I realized why I have appreciated his book on Old Testament theology so much. His approach is one that I can understand. He looks at the evidence honestly and with eyes and ears and heart that appreciates the message. This isn’t just an academic exercise, nor is it a matter of toeing some doctrinal line. Genuine faith seeking understanding.

How does his approach strike you? Is is dangerous or valuable?

How would you respond if Moberly was in your church?

Unfortunately Moberly’s is an approach that is suspect in much of the evangelical church. It can lead to scholars being unwelcome, or merely tolerated in the church. Tolerated, at least, if they keep quiet and hold their disruptive questions and observations to themselves. I’ve learned that keeping quiet is often the best approach. It can be either that or forgo most Christian fellowship altogether.

Another Scholar, Another Story. Some of the other chapters in the book tell similar stories of genuine faith seeking understanding. This can have consequences. Bruce Waltke writes of how he left his position at Dallas Theological Seminary when he realized that he could not sign the statement of faith without reservation. It wasn’t that he then disagreed with the statement, but he couldn’t think through the issues about which he had some reservations while remaining at Dallas.

But before this he was challenged as a Ph.D. student at Harvard in Ancient Near Eastern Literatures and Languages.

Whereas Dallas focused on the dissimilarities between the Old Testament and ancient Near Eastern literatures, Harvard emphasized their similarity, and this similarity makes the Bible appear to be a very human – not a divinely inspired – book. The cosmogony of Genesis 1 is similar to the pagan cosmogonies of the biblical world; Moses’ book of the covenant at some points repeats word-for-word the Code of Hammurabi; the war annals of the historical book resemble those of the pagans; David’s psalms are similar to Sumarian, Akkadian, and Canaanite hymns; and Israel’s prophets find their counterpart in other ancient Near Eastern religions. (p. 244)

But the Bible isn’t merely a human book. The theology is totally dissimilar, and the Bible is primarily a theological book. It’s importance to the church is the theological message. That the forms are similar isn’t terribly surprising. After all, the authors were shaped by their language and culture. Waltke reflects:

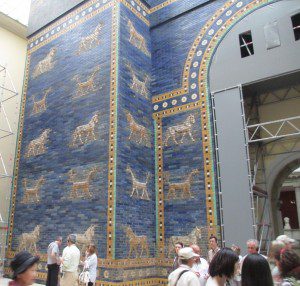

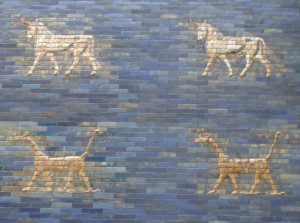

When I went through the Ishtar Gate at Babylon and saw the image of Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, with his dragon-like head, lion-like torso covered with fish scales and his serpentine tail, I thought to myself: “No wonder Daniel had visions of incredible animals.” Probably, Moses, who had the finest education of his day, was familiar with other law codes and God used his education in formulating the law. (p. 244)

My husband and I saw the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin this summer. It is truly impressive, with Marduk (lower pair in the image to the right – click for a closer look) and aurochs symbolizing Adad (upper pair), and many lions along the way. He remarked that anyone teaching Daniel should include images of the Ishtar gate. It is far more impressive than any mental image he had ever had from 50+ years in the church and countless sermons and lessons. How must the captives have felt when taken to the grandeur of the city and the palace? Certainly this shapes the way the stories are told.

My husband and I saw the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin this summer. It is truly impressive, with Marduk (lower pair in the image to the right – click for a closer look) and aurochs symbolizing Adad (upper pair), and many lions along the way. He remarked that anyone teaching Daniel should include images of the Ishtar gate. It is far more impressive than any mental image he had ever had from 50+ years in the church and countless sermons and lessons. How must the captives have felt when taken to the grandeur of the city and the palace? Certainly this shapes the way the stories are told.

Waltke notes that “now he has come to regard the canonical form of the book of Deuteronomy as a post-exilic work that recounts the history of Moses’s writing of the book of the law, which comprises all but fifty-nine verses of the book of Deuteronomy.” (p. 247) Likewise that Isaiah as written by two authors, say Isaiah and his disciple, is supported by evidences of style and audience and is consistent with the book of Isaiah as Scripture.

I am not a Fundamentalist, who stands upon the Word of God, convinced that my preconceived interpretations of my tradition are right or that my interpretations are inerrant. Rather I stand under the Word, trying to understand how and what it means. (p. 248)

Waltke’s conclusions do not always agree with Moberly’s. He remains somewhat more conservative I believe. But the ground is similar: faith seeking understanding going with the evidence. Comfortable with a level of uncertainty and the open discussion of the questions surrounding the Old Testament, he draws the line between the radical naturalism and skepticism of the modern academy and faith in God rather than a fence around some preferred and “safe” interpretation to be defended at all costs.

Bruce Waltke has paid for his scholarly integrity at times. Not all appreciate this approach, and some fear his conclusions.

I wish all pastors understood that this is picture of good Christian scholarship not a threat to the faith.

Is there room for faith seeking understanding in the church?

What does this mean in your context?

I Wish Pastors Knew … Part 2 will address the issue of scholarship and the church more broadly.

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.