Jeremiah was a prophet in Jerusalem at the time leading up to the Babylonian captivity. He was freed from confinement by King Nebuchadnezzar and recorded the troubling reactions of the people of Judah during this cataclysmic event. Jeremiah 18:1-12 is a troublesome passage for many interpreters. Walter Moberly in Old Testament Theology: Reading the Hebrew Bible as Christian Scripture refers to this passage as “the passage whereby all other depictions of divine repentance elsewhere should be understood, when one is reading the Old Testament as canonical scripture.” (p. 116)

Jeremiah was a prophet in Jerusalem at the time leading up to the Babylonian captivity. He was freed from confinement by King Nebuchadnezzar and recorded the troubling reactions of the people of Judah during this cataclysmic event. Jeremiah 18:1-12 is a troublesome passage for many interpreters. Walter Moberly in Old Testament Theology: Reading the Hebrew Bible as Christian Scripture refers to this passage as “the passage whereby all other depictions of divine repentance elsewhere should be understood, when one is reading the Old Testament as canonical scripture.” (p. 116)

First the text (NIV):

This is the word that came to Jeremiah from the Lord: “Go down to the potter’s house, and there I will give you my message.” So I went down to the potter’s house, and I saw him working at the wheel. But the pot he was shaping from the clay was marred in his hands; so the potter formed it into another pot, shaping it as seemed best to him. (v. 1-4)

Then the word of the Lord came to me. He said, “Can I not do with you, Israel, as this potter does?” declares the Lord. “Like clay in the hand of the potter, so are you in my hand, Israel. (v. 5-6)

After noting that the passage refers to Israel, i.e. God’s chosen people as a whole, not simply to Judah and Jerusalem where Jeremiah spoke, Moberly continues:

The imagery is also striking. For if a potter’s ability to do with the clay as he wishes (v. 4) illustrates the power of the maker over that which is made, then such imagery applied to God (v. 6) intrinsically symbolizes divine power. The imagery is not that of interpersonal relationships, which is the predominant biblical idiom for depicting God and Israel; king and subjects, master and slave, husband and wife, father and son are perhaps the most common images. … But with a limp of clay a potter has no relationship or responsibilities – it is an object to be used and shaped at will. When applied to God, therefore, the imagery of potter (yōtsēr) does not evoke mutuality, but rather unilateral power. (p. 116-117)

This imagery makes the sequel surprising. The next several verses do not depict divine power, “but rather divine contingency and responsiveness.”

If at any time I announce that a nation or kingdom is to be uprooted, torn down and destroyed, and if that nation I warned repents of its evil, then I will relent and not inflict on it the disaster I had planned. And if at another time I announce that a nation or kingdom is to be built up and planted, and if it does evil in my sight and does not obey me, then I will reconsider the good I had intended to do for it. (v. 7-10)

The incongruity has led some to suggest that distinct passages have been placed together by some (careless) editor. But this isn’t adequate, certainly not if we read the Old Testament as scripture. The text as received is intended to convey meaning, whether edited from sources or a unified original composition.

The incongruity has led some to suggest that distinct passages have been placed together by some (careless) editor. But this isn’t adequate, certainly not if we read the Old Testament as scripture. The text as received is intended to convey meaning, whether edited from sources or a unified original composition.

A fundamental presupposition within 18:7-10, therefore, is that God’s relationship with people is a genuine relationship because it is responsive. The relationship between God and people is characterized by a dynamic similar to that of relationships between people: they are necessarily mutual, and they can both grow and wither. How people respond to God matters to God, and affects how God responds to people. (p. 120-121)

Moberly notes that this isn’t an equal relationship, and the way in which God repents or changes is not the same as the way in which people are called to change. This is reflected in the words used. Humans turn/repent (shūv) while God “repents” (niḥam). The NIV reflects this using relent and reconsider for the action of God. The NRSV favored by Moberly uses “change mind” but none of these really seem to capture the meaning completely. Moberly suggests that rescind, revoke, repeal, or retract may capture the meaning more closely.

This leads (after a brief side trip to Ezekiel) to three points:

First, In this passage God, the potter, commits Himself to responsive action. “Divine power is exercised not arbitrarily, but responsibly and responsively, interacting with the moral, or immoral, actions of human beings.” (p. 123)

Second, a skilled potter, like any artist, is responsive to the material, in this case clay, which is worked.

Second, a skilled potter, like any artist, is responsive to the material, in this case clay, which is worked.

This enables one readily to read, or perhaps rather reread, verses 7-10 as depicting an interaction between potter and clay; the initial imagery of the potter’s power can be complemented by thoughts of his responsiveness. Correspondingly, those identified as clay should think of themselves not as helpless objects dependent solely upon the decisions of the potter, but rather as able to make some difference to him. Since the potter’s decisions about what to do depends on the quality of the clay, the point becomes clear: “Let the vessel therefore make sure it is worth keeping.” (p. 123)

Third, verses 7-10 are not specific to Israel. “God’s dealings with Israel and with others, the elect and the non-elect, do not differ. The dynamics of responsiveness and contingency apply alike to all.” (p. 123)

The passage in Jeremiah continues:

“Now therefore say to the people of Judah and those living in Jerusalem, ‘This is what the Lord says: Look! I am preparing a disaster for you and devising a plan against you. So turn from your evil ways, each one of you, and reform your ways and your actions.’

But they will reply, ‘It’s no use. We will continue with our own plans; we will all follow the stubbornness of our evil hearts.’” (v. 11-12)

The NRSV makes the connection between v. 11-12 and v. 1-6 more explicit.

The NRSV makes the connection between v. 11-12 and v. 1-6 more explicit.

Now, therefore, say to the people of Judah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem: Thus says the Lord: Look, I am a potter shaping evil against you and devising a plan against you. Turn now, all of you from your evil way, and amend your ways and your doings.

The people are warned to repent, YHWH is fashioning disaster against them and will use the might of Nebuchadnezzar and Babylon to bring this about. Yet the people will refuse. They are refusing as Jeremiah speaks, time and time again.

In the next section of this chapter Moberly turns to passages where God’s repentance (niḥam) is denied as a matter of theological principle. But this discussion of Jeremiah is worth our focus today.

Does this reading of the responsive potter change your view?

Is the imagery of God as potter consistent with the image of God as responsive to human action?

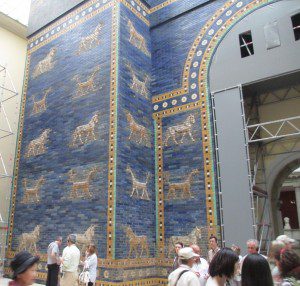

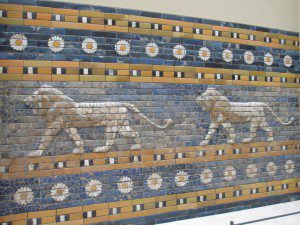

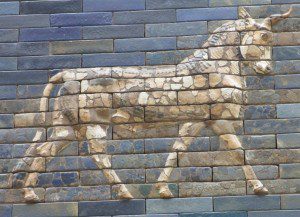

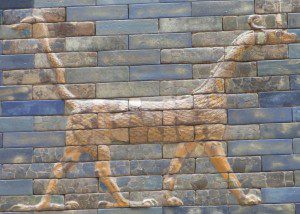

The images in this post are of Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate, built around 575 BC, a smaller but impressive portion of which has been reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. They are but marginally related to the post – but God used Nebuchadnezzar, and he held the king of Babylon and his people responsible for their actions.

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.