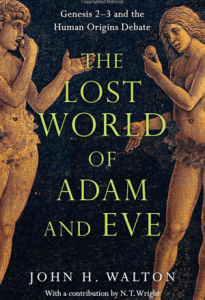

John Walton sums up his book The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate by asking why it matters that we dig into the question of Adam. Aren’t we simply letting science dictate the terms?

John Walton sums up his book The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate by asking why it matters that we dig into the question of Adam. Aren’t we simply letting science dictate the terms?

The historicity of Adam and Eve is significant for two reasons: inerrancy and The Fall. On the first point Walton has argued that Genesis is an ancient text and it is only natural that God would accommodate his message to the understanding of the original audience. We need not affirm everything mentioned in the text if it is incidental to the message of the text. Such an approach has ample support in the history of Christianity. Walton brings up John Calvin’s commentary on Genesis 1 as an example. That Saturn is larger than the moon, or that the moon “only” reflects sunlight, does not mean that there is an error in the text of Genesis. This is an accommodation to the level of the audience.

Walton turns to an earlier book, Four Views on the Historical Adam, where he presented a sketch of the argument made in much greater detail in the current book. Philip Ryken offered one of two pastoral responses (Greg Boyd offered the other). Ryken argued that we need a historical Adam. His reasons are summarized by Walton (p.. 203):

- The historical Adam explains humanity’s sinful nature.

- The historical Adam accounts for the presence of evil in the world.

- The historical Adam (with the historical Eve) clarifies the biblical position on sexual identity and family relationships.

- The historical Adam assures us that we are justified before God.

- The historical Adam advances the missionary work of the church.

- The historical Adam secures our hope in the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting.

Walton points out that these reasons illustrate the truly significant questions in the discussion of Adam. Inerrancy is a rather minor one that can, if these other issues are addressed, be handled rather easily (for most of us at least).

But Walton doesn’t address these issues specifically. Rather he argues that

… even if we accept without question all these points, we could still maintain that no theology is built upon the scientific implications commonly associated with Adam and Eve: that they must (theologically speaking!) be created de novo, as the only people at the beginning of humanity and those from whom we are all still descended. (p. 203-204)

This has been the thrust of his book. It isn’t that we have answers about everything. Simply put, the traditional interpretation of a unique pair isn’t the only interpretation that is faithful to scripture and to the theological claims of scripture. And this is important:

In other words, if neither exegesis nor theology intractably demands those conclusions that argue against modern scientific consensus premised on common descent, we have no compelling reason to contest the science. (p. 204)

We don’t interpret scripture through the lens of science, looking for concordance with modern science, but concentrate on the theological message of scripture and let science wander along the path to truth. There is certainly no guarantee that all we affirm today with respect to human evolution is “truth.” And it certainly is not true that the atheistic, materialistic, naturalistic statements made by some scientists must be accepted as truth. But the science itself need not be feared or resisted.

But, but, but, … what about tradition!

Some readers will feel some reticence about adopting new interpretations of the biblical text. How dare we disregard two millennia of church history? Are we better than the church fathers? Would God leave us without sound interpretation for so long? These sorts of questions show a commendable impulse to caution. As we address these concerns, however, we might recall that opponents of the Reformers would have raised similar objections. Furthermore it is noted that in this work the suggested innovations are primarily exegetical rather than theological. (p. 204)

We would do well to remember that all of the church fathers (and the Reformers) were human beings limited by their time, place, and resource. For example, we have access to a million cuneiform texts unknown to the church fathers. We also have knowledge of the natural world – not just deep history and cosmology, but also geography, flora, and fauna – that is completely foreign to them. We would also do well to look into the diversity of interpretations throughout history. They are not as uniform as we often suppose.

Here is a key point:

These comments do not suggest that we neglect or ignore the history of interpretation, only that we recognize that a history of faithful interpretation continues and that as the textual evidence dictates, we may still find occasion to take our departure from some traditionally held ideas. (p. 206)

Walton doesn’t put it like this, but I will. God did not put us on autopilot 2000 years ago, 1500 years ago (after the Nicene Creed), 500 years (after the reformation), 100 years ago (with the rise of fundamentalism in the US), or yesterday. We have to wrestle with God’s message afresh in each new generation in the changing contexts of life trusting his Spirit to lead us forward. The canon is closed, but the Spirit isn’t absent.

And why does it matter? Here I find it interesting that Ryken claims that a historical Adam advances the missionary work of the church. It is clear that a united humanity does this – but that doesn’t require a historical Adam. Nor does a historical Adam necessarily lead people to appreciate the full humanity of all (David N. Livingstone’s books Adam’s Ancestors and Dealing with Darwin bring important insight into the various influences in our church history).

Walton suggests that this discussion matters for reasons of mission, ministry, and evangelism. Unnecessary certainty on issues that conflict with science marginalizes those who understand the science. It leads to an unhealthy bifurcation of life into “church time” where we “church think” and “professional time” where we “science think.” This is not a comfortable position. It would be far better to chart a path of convergence and compatibility if such does not compromise on the theological core convictions of our faith.

The church’s approach to science also has a significant impact on evangelism. “Many non-Christians opposed to the gospel and to Christianity habitually ridicule the church for what they paint as a naive commitment to an ancient mythology.” (p. 208) We should be careful to present the gospel and not encumber it with non-essential opinions and interpretations. Walton concludes “The gospel is clear – believe in the Lord Jesus Christ and you will be saved.” (p. 209)

I’ll go a little further … Not only is the gospel clear, but the historical Adam isn’t important to it at any level. It is Jesus Christ who assures us that we are justified before God. It is Jesus Christ who advances the missionary work of the church. It is Jesus Christ who secures our hope in the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting. A Christian who never hears about Adam, but is taught the life, death, and resurrection of Christ lacks nothing.

Getting our priorities straight does matter. I am always willing to discuss the science. But this isn’t the main point. Jesus Christ is. When we equate the gospel with a preferred presentation of the gospel we have a problem and it is hurting our witness.

Does the historical Adam matter?

What theological point stands on the traditional view of Adam?

Does it matter that this view prevents many from even considering the gospel message?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.