I have to admit that the conclusion to Mark Harris’s book The Nature of Creation (both the chapter on Scientific Eschatology and New Creation and the concluding chapter itself) leave me somewhat befuddled. There are a number of clear (and useful) points, but less clarity concerning the nature of creation and new creation and what these should mean to the Christian. Perhaps this confusion is unavoidable given the complexity of the topic.

I have to admit that the conclusion to Mark Harris’s book The Nature of Creation (both the chapter on Scientific Eschatology and New Creation and the concluding chapter itself) leave me somewhat befuddled. There are a number of clear (and useful) points, but less clarity concerning the nature of creation and new creation and what these should mean to the Christian. Perhaps this confusion is unavoidable given the complexity of the topic.

Harris has outlined two forms of creation – creatio ex nihilo and creatio continua, creation out of nothing and continuous creation in earlier chapters. In this last section he adds a third form of creation into the mix – creatio ex vetere, creation from the old.

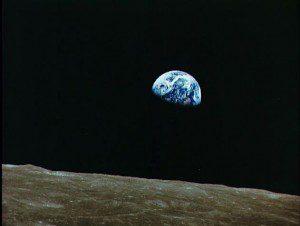

Science really cannot shed much, if any, light on eschatology. What science has to say about the end of the world has little to do with the biblical vision. This shouldn’t be surprising – the new creation arises as a fresh start from the old. It is a redemptive creation and “redemption is always a divine action.” (p. 167) This is true in the exodus, in the Old Testament prophets, and in the apocalyptic literature. It is a message of hope that reflects a change in the current social and political situation and a completely new beginning for creation, the latter primarily in the later apocalyptic writings.

Harris argues that “any description of divine action must be metaphorical by definition.” Biblical texts fall into a number of different categories. Some are historical – accounts of kings and battles and such. These we can interpret in the light of our experience (although it also helps to understand the ancient Near East.

There is, however, a profound difference when we are seeking to understand a biblical text which describes something entirely out of our experience, such as a miracle, or a divine action, even one of creation. And the prophecies of new creation, by their very nature, concern divine action, and new action at that. Clearly all talk of contact between the divine and the earthly must then be inherently metaphorical, an attempt to explain the otherworldly in terms of our world. But this is all that we can do: speak of the new creation using language of our creation, images from our world which refer to a reality coming from another world. (p. 174)

The resurrection of Jesus and the resurrection body is our only real point of contact. This, of course, we only know of through the text of scripture – through human language inadequate to the task of description. It is something new for which the words and ideas dis not really exist in first century Greek.

The second coming is also an important part of the picture, although again portrayed in metaphorical, figurative language. But that we are to interpret it as an actual material return is unquestioned.

But at root, the idea of the second coming articulates an important theological point about the Christian slant on the new creation. Just as God chose to be revealed as a human being in the incarnation, inorder to redeem creation, so God will do so again at its completion. (p. 175)

The resurrection is an example of creatio ex vetere, creation from the old. There was discernible continuity with his pre-death body and something new as well. This “was more than the resuscitation of a corpse.”

Conclusions. None of the creation texts in the bible should be pinned down to a single physical meaning. This shouldn’t surprise us as the ancient Israelites (like other ancient authors) were capable of sophisticated literary thinking. If we view them as “primitive” we will get nowhere. The creation texts display a depth of thinking and imagery. Harris summarizes it well:

Conclusions. None of the creation texts in the bible should be pinned down to a single physical meaning. This shouldn’t surprise us as the ancient Israelites (like other ancient authors) were capable of sophisticated literary thinking. If we view them as “primitive” we will get nowhere. The creation texts display a depth of thinking and imagery. Harris summarizes it well:

Creation is a major theme in the Bible, with many diverse strands and layers of meaning, but we have seen that modern science only impacts on them on a surprisingly superficial level. While we can pinpoint traces of an ancient scientific view in the texts which is clearly superseded in our modern perspective, yet it served wider theological aims that are still relevant. In other words, the fact that the Bible’s creation texts are drastically outdated from a scientific point of view has not invalidated their various portraits of the relationship between God and creation; indeed modern science can say very little directly about this relationship. Furthermore, against the reductionist tendencies of science, we found that the Bible takes a much more expansive approach. Its creation texts can rarely be pinned down to a single level of meaning, a single interpretation, or a single explanation, and certainly not an explanation in terms of physical reality alone. (p. 185)

Another way to say this is to point out that the creation texts were never intended to simply convey physical realities. They convey a theological message. The ancient scientific view found at times in the text is incidental to the message. God, through the text, uses the views of the original audience concerning “scientific” questions. No new science is introduced in the text.

The creation texts in scripture describe the relationship of God with the world. Creation out of nothing is “best expressed as a statement of God’s transcendence.” Continuous creation “is most clearly an expression of God’s immanence.” God is in intimate relationship with humans and the rest of creation. Creation from the old “is fundamentally a descriptive term for God’s redemptive activity in creation. (p. 186) Creation from the old is clearly connected with the resurrection of Jesus, but is seen in other texts and situations as well.

These three aspects of creation are simplifications and should not be separated rigorously.

God’s work of creation ex nihilo, continua, and ex vetere are not three different actions, but one creative action, while at the same time they point to the diversity and diversity of the unitary God. It is no accident that this is reminiscent of Trinitarian language of God – three in one and one in three – for it was through observations such as these, of God’s diverse work in the theatres of creation and redemption, that the three persons of the Trinity came to be recognized and distinguished as such. But the three categories of creative work are not to be identified with the three persons of the Trinity; rather it is distinctions such as these that have been important in the development of Trinitarian thinking. (p. 187)

Finally we note that it should not be surprising that the world is comprehensible, subject to mathematical description and analysis. The book of nature reflects the mind of the Creator God. Harris sums it up:

The Bible’s creation texts therefore supply us with an explanation for the miracle of modern science, namely its unstoppable success in understanding the physical world: it is because science taps directly into the mind which made it all. (p. 193)

All in all an interesting book (although I’ve skipped the more esoteric scientific, philosophical, and theological discussions in my summaries). An academic book, but one I’ve found worth the time and energy.

In what ways does the Bible emphasize the three aspects of creation described by Harris (out of nothing, continuous, and from the old)?

Is Harris right that metaphorical language is required to describe divine action – something outside our material realm?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.