Yesterday Jordan Monge asked the question “why don’t we talk about friendship more?” The post was prompted by a talk she heard given by Wes Hill on the topic of spiritual friendships. (For what it’s worth, you really should start reading Wes’s blog on a regular basis.) This is an issue I’ve thought about a good bit because of the role friendship has played in my own life.I’ll get to some causes of our neglect of friendship below, but first I want to give some personal background that informs my perspective. I’m part of a group of 11 friends from college who are now all in our mid to late 20s (the youngest members of the group are 24, the oldest 28). We all met at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and have managed to maintain our friendships from afar. (There are now only two of the original 11 still living here in Lincoln.)

The first weekend we all hung out as a group was the weekend of one of our member’s wedding, which is how one half of our group met the other half. We were all brought together at the rehearsal and, about six hours later, after doing our best impression of the Inklings (smoking, drinking good beer, and arguing about theology), we found that we enjoyed being together. And when Eric returned from his honeymoon, he found friends from one group hanging out with friends from the other group. And we’ve been together ever since.

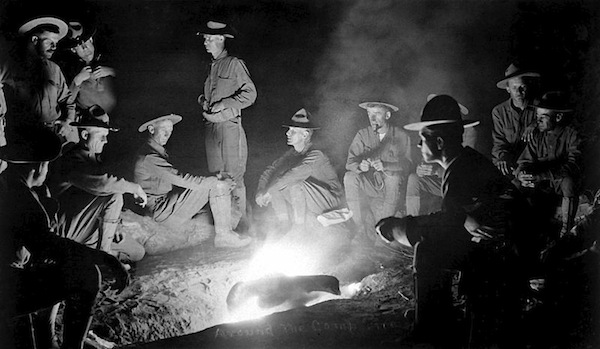

The high point of the year is our three day summer gathering. We meet in late July or early August for three days with no agenda other than being together. So far we’ve rented a cabin, borrowed a family member’s RV (yes, 11 guys in one RV… fun times, let me tell you, the fact that it was 100 degrees out really put it over the top) and twice used the attic of our home church in Lincoln. Our weekend consists of drinking beer (everyone brings a six pack or two of a microbrew from their current city), revisiting our favorite Lincoln restaurants, playing yard games, and singing for an hour or two every night, usually starting with Josh Ritter, Mumford, Johnny Cash, The Magnetic Fields, and Jonathan Coulton before moving on to Indelible Grace hymns as well as some of Derek Webb’s older songs. In the midst of all that, we also find time to talk, share what’s going on in our lives, what’s been hard in the past year, what’s been good, and so on and pray for each other. It’s an odd ritual, I suppose, but it suits us.

That’s all to say that friendship has played a major role in my life and that I suspect it will for the rest of my days. But not many people have the kind of friendships that our group of 11 enjoys. Why is that? I suspect there’s a few things feeding into our struggles for friendship.

First, the structure of our lives in the USA today makes friendship increasingly unlikely. Most of us work 40 hours a week (and spend another several hours commuting), which puts significant limitations on what we’re able to do socially. It’s no coincidence that most of our deepest relationships are formed in college when we live in close proximity to each other and have plenty of unscheduled time. Additionally, most of us tend to follow our professional ambitions wherever they lead, which in the best case scenario leads to living in the same city as your friends, but everyone being separated by a 30 minute drive or ride on the mass transit system. More realistically, our captivity to professional ambition leads to all of us ending up scattered across the country. And short of special desires to stay in touch during the year and the willingness to schedule several days to be together every year, friendships will wither over such distances. To put it simply, friendship is increasingly inconvenient and costly in a nation where our free time is so drastically limited and where the pressure to pursue professional success is so strong.

Second, I think the reason marriage continues to be discussed so prominently in the church while friendship is neglected is that we can identify a unique social benefit to marriage, but we struggle to do the same for friendship. We expect people to need marriage but to be able to make due without deep, abiding friendships. Simply put, in the church we tend to treat marriage as a necessity and friendship as either a luxury or, at best, a lesser necessity than marriage. That’s a mistaken way to think, of course, but it’s also the on-the-ground reality in many churches.

Third, because our lives and communities don’t really allow for deep friendships by their basic structure, we tend to adopt the idea that we don’t really need friendship. I think every member of our group of 11 would recognize that as a monstrous lie, but unless you’ve seen your life dramatically changed by friendship, it’s hard to recognize that need without experiencing it first. It’s rather like a person living in a home without running water surrounded by neighbors whose homes do not have running water. None of you recognize a need because you don’t know that such a thing as “running water” exists. You can make due without it indefinitely and you don’t really realize how valuable it is until you already have it or have seen someone else who has it. It’s not the sort of thing for which you can discover a need completely on your own because rather than naming that need you’ll find ways of coping with the lack.

Fourth, this is a subtle point but an important one. Within our group of 11 friends, one of us in particular has played a really vital role as the networker who brought us all together. His name is Eric and he’s the one who got married that first weekend when we all met. Eric is a strong extravert who enjoys introducing people to each other. He’s also something of a polymath who has a seminary degree, loves role playing games, can do a ton of magic tricks and other card tricks, has read a ton of political and economic theory, and writes poetry in his free time. How he finds free time while working full time and raising a three-year-old and a seven-month-old is another question, but somehow he manages.

Put another way, he’s a connector with a ton of personal interests and hobbies. That unique gifting gives him a rare ability to bring people together. Eric isn’t the center of our group or that he’s somehow more important than the rest of us. But when certain personality types are missing, groups suffer and individual relationships do too. Without Eric, many of us in the group would not have met each other and would not have been able to befriend each other as easily as we did. Our group might still have happened, but it wouldn’t have been the same. So I suspect that one thing we need to recognize is that different people have different giftings and callings and we need to provide people support and encouragement to use those gifts for the good of the church. Simply by being his extraverted polymath self Eric was able to help all of us develop relationships that will sustain us through life and carry us to our graves. There may be any number of communities where friendships could develop more easily but don’t because they either don’t have an Eric or the Erics in their communities aren’t using their gifts.

What’s the fix, then? There isn’t an easy one, but a few things that would help would be placing a greater value on rootedness in our churches (and probably a fair few sermons calling out our sinful ambition for what it is). We also need to think carefully about where we live and where we work and do as much as possible to keep the two places closer together. If we have to work 40 hours a week, we should at least try to avoid spending five hours per week commuting. These ideas, of course, are only a start. But if we’re going to see the cultivation of a community of friendship within the church, these are the sorts of things we’ll need to do.

[Image of campfire from Wikipedia]