Calling people dogs seems to be common these days. But Jesus called a woman a dog. Why can’t the president? Why can’t we? What’s the difference? Careful study of this text from Mark 7:25 – 30 shows us that there is a huge difference.

Exhibit A.

A woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. 26 Now the woman was a Gentile, of Syrophoenician origin. She begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. 27 He said to her, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” 28 But she answered him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” 29 Then he said to her, “For saying that, you may go—the demon has left your daughter.” 30 So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone. (Mark 17:25 – 30).

Exhibit B.

“You wouldn’t believe how bad these people are. These aren’t people. These are animals.”

Exhibit C.

“When you give a crazed, crying lowlife a break, and give her a job at the White House, I guess it just didn’t work out. Good work by General Kelly for quickly firing that dog!”

In light of our Gospel passage today from Mark 7:24 – 37, we might ask: Well, if Jesus called a woman a dog, why can’t the president?

What’s wrong with calling people dogs, calling them ‘animals’?

I’ll admit, growing up, I heard this kind of language from certain family members. We would drive through a particular section of town where black families lived and my family member would always say, “Look at all those porch monkeys. Better lock your doors.”

What did this communicate to my young mind? These people were different, less than human, possibly entertaining, but not to be trusted. Dangerous, like wild animals.

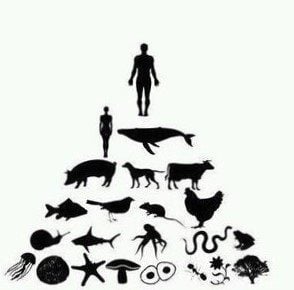

Of course, in one sense, all human beings are, in fact, ‘animals.’ We are all mammals. We’re warm-blooded, we nurture our young, we have hair. That is a biological fact.

But when people use that word to insult other people, they are working from a commonly held worldview wherein humans occupy the top of the moral pyramid, and animals lurk at the bottom. It’s part of a pattern of seeing people who are unlike ourselves as beasts or monsters.

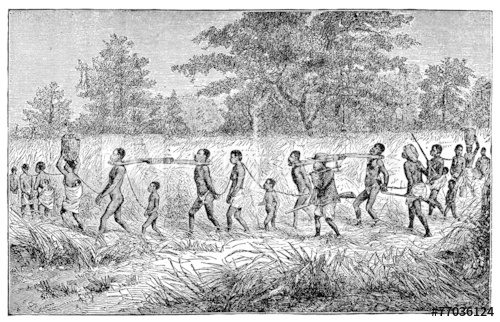

Our language animalizes people, thus dehumanizing them. We call women “cows,” “cougars,” and other words I can’t say in the pulpit. White people have called black people “coons,” “apes,” and “dogs.” And did you know that it was a practice in medieval Europe to hang an ape and a dog on the gallows when a Jew was executed?

See, if a person is not truly human, logic dictates that they can be brutalized and exterminated like any other nuisance or threatening beast. It hearkens back to whites in the 1600’s (and continuing to this day) labeling people in Africa as “savages” and “beasts.” This opened the way to treating them as such – animals to be owned, worked to death, beaten, raped, and killed for sport.

Certainly, this is not what Jesus intended when he called the Syrophoenician woman a dog. But his words make us cringe, nevertheless.

In his exchange with the woman – whose tribe was outside of his own – when she is begging for healing for her daughter, Jesus words are like fingernails on the chalkboard.

“It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs,” (v. 27).

Ouch. This falls into the category of “Things I Wish Jesus Had Never Said.”

What are we to do with these words from Jesus? If Jesus called people dogs, why can’t we? Why can’t the president?

After having consulted with key scholars on this text, including Amy-Jill Levine, a Jewish New Testament scholar at Vanderbilt Divinity School, and my colleague Jerry Sumney, who teaches New Testament at Lexington Theological Seminary, I have to say that there’s no way around the conclusion that what Jesus says is problematic, at best. Jesus is calling both the woman and her people “dogs.” This would have been considered a cross-cultural insult during Jesus’ time, and it is certainly an insult today.

Why would Jesus say such a thing?

It’s a complicated question. But we have to ask it in tandem with another question.

What do we make of this woman who replies with a clever, yet humble response, that shifts the dynamic and results in healing for her daughter?

“Yes, Lord, but even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ tables.”

You can imagine the scene – the hush coming over the crowd to see how Jesus will respond. He could have fired back, “How dare you! You need to learn your place!” And then told his disciples to do away with her.

But instead he responds, “For saying that, you may go—the demon has left your daughter.” The tension releases; the crowd (and the woman) exhales.

The point of this text is to show what Jesus’ healing looks like in a way that upends our expectations. The original readers of the gospel would have recognized the familiar trope of a person in a subordinate position cleverly getting the better of a superior. The story does two things. It emphasizes the great faith of the woman AND it shows us that Jesus is the model teacher.

A model teacher? By calling this woman a dog? How can that be? How is Jesus modeling good teaching by calling this woman a dog?

It comes in verse 29 when he changes his mind.

Here’s the key: Jesus listens and learns.

Now I realize that the idea of Jesus needing to learn something may be shocking, even offensive, to some. Jesus was perfect, wasn’t he? Why would the Son of God need to listen and learn from anybody, let alone a lowly woman desperate for healing who is not of his own people?

But remember, for Christians, Jesus is human as well as divine. And as a human, he was a product of his time. His people did not accept her people. Neither of their tribes got along. Insults were traded between their peoples for centuries. It’s only natural that Jesus would respond to the woman the way he did.

But of course, that does not justify what he said.

He was wrong to call her a dog. And she called him on it. But she did it in a way that simultaneously de-escalated the confrontation, while still standing firm and persisting for the healing she needed for her daughter.

This passage captures an important moment. When the woman points out the fallacy of Jesus’ thinking, he learns from it and changes his attitude. He’s essentially saying – you got me! You’re right. I was wrong. You didn’t deserve that insult. You’re clever and brave. You’ve got chutzpah!

I give you what you’ve asked for, what I should have given you right from the start – healing for the daughter you love. The daughter you are desperate to save. The daughter I should care about as much as I cared for Jairus’ daughter who I raised from death. As much as I cared for the woman who I freed from seven demons. The woman who I freed from a crippling back deformity. The woman who was healed instantly as she touched my cloak. I called her “Daughter.” But I called you and your daughter “dogs.” That was wrong of me. I’m sorry. I’ll be better. I’ll “be best.”

See, that’s the difference between what happens when Jesus calls someone a dog, and when certain other individuals call people dogs. Jesus made a mistake. He admitted it. He fixed it. And he learned from it. Things got better.

“A model teacher is one who can learn,” Levine reminded me in a conversation about this story. “If Jesus has nothing to learn, and if he is not going to listen to others, then he is not a teacher, he is not in relationship, and he is not human.”

Levine further explained what Jesus came to realize by the woman’s response to his insult. “Jesus realizes that he can yield his own position of authority, his own job description, for the sake of someone who has no authority of her own. This yielding shows he cares about the people. And more — he listens to them. She, on the other hand, demonstrates Jesus’ teaching: she persisted, cleverly, without elevating the violence. Everyone wins.”

The readers of Mark’s Gospel, both elite and peasant, both outsiders and insiders, learned something from this story.

What will we learn?

In light of the kind of rhetoric we hear and read from the Oval Office, the alt-right, the KKK, neo-Nazis, and white-supremacist websites, we must be very clear that what Jesus said in First Century Palestine is not acceptable to say to another human being. Christians must state unequivocally that such language must never be used about women, Jews, non-Jews, foreigners, people of color, people of different sexual orientations, people of other religions.

The Syrophoenician woman was not a dog. Her daughter was not a dog. Her people were not dogs. We must never, ever animalize or otherwise denigrate another human being or group of people deemed as “other.”

Dehumanizing those we dislike does not lead to constructive solutions.

We must find better ways to use our words. Calling people “animals” is wrong, dangerous, and reminiscent of authoritarian rhetoric used to rationalize exterminating entire populations of people. And it demonizes animals by projecting on to them the worst of human traits. [See: Mr. Trump, Here’s What’s Wrong with Calling People ‘Animals’]

So what do we do with a passage like this?

Here’s where it’s important to understand that the Bible is often DESCRIPTIVE but not PRESCRIPTIVE. Just because Jesus uttered these words does not mean we should follow his example. Just as it is no longer acceptable to repeat the kind of racist language, jokes, innuendoes, or hate speech uttered by our parents and grandparents, our co-workers, our spouses, our friends.

The good news here is that, like Jesus, we can learn. We can change our attitude. We can make different choices. In his final response to the Syrophoenician women, Jesus modeled what it looks like to change our minds and initiate healing. At the very least, we can change our minds and initiate healing as well.

Leah D. Schade is a professor of preaching and worship and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is an ordained minister in the Lutheran Church (ELCA).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

Read also:

Mr. Trump, Here’s What’s Wrong with Calling People ‘Animals’

Gaslighting in the Age of Trump: 6 Tips for Survival

What Child Would Jesus Cage? Christians Join Rally for Protecting Immigrant Families