Like most of my good ideas, this one happened by accident.

Four days into the Lenten season, I had nothing — no fast, no practice, no structure for the 40 days — even though I had spent most of January talking up the season to my two sons. We had gone to our Ash Wednesday service and imposed ashes on each other’s foreheads. But I was in danger of losing that teachable moment about follow-through and commitment in spirituality.

For myself and for them.

One morning, (after voting in Lent Madness), I picked up Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints, the Episcopal Church’s liturgical book commemorating our faith’s saints, luminaries, and divines. On a whim, I invited my children to the kitchen table before school to start our family Lenten practice together.

I cheated, technically. Even though it was a few days later, I began that morning with Feb. 12, a day intended to remember Charles Freer Andrews, a priest and “friend of the poor” in India. Using the biography provided in the book, I told my children the story of a man who worked for justice for the poor, who stood against racism, embraced nonviolence and worked across cultures and faith with other divines like Gandhi.

Much to my surprise, my children were into it, and by “into it” I mean they didn’t get up from the table and go build with their Legos before we finished. We closed by praying the collect for the day. And then, they went about their day in a holy silence, meditating on how they too could live out the gospel in such a radical way raced to the car, pushing each other out of the way to get there first, and spent the whole ride to school bickering about whose favorite song was better. Despite the inauspicious start, we stuck to it (most days, at least). Often, we were just lucky to make it through our daily saint without prayers devolving into animal noises and elbows, but the boys became attached to the morning ritual nevertheless.

Some days, I was no better, completely forgetting our practice in one of those mornings where everything is happening 10 minutes late because the oatmeal burned and I stayed in bed listening to NPR rather than making lunches. One morning in particular, I was grouchy and late and even a third cup of coffee didn’t help. I shuffled the kids into the car in a less-than-priestly way and was halfway out of the driveway when my oldest piped up softly from his carseat and pierced my bad mood.

“Daddy, we forgot to do our saint today,” he said.

Not willing to let go of the grump inside me, I told him we would do it that afternoon.

Then he started to cry. And I felt like a terrible father and wondered how in the world I would ever make it as a priest. I darted inside and grabbed the Saint Book.

But, every now and then, something special happened, and my children asked questions about the saints and their work. We talked about racism and slavery in the United States when we remembered Absalom Jones and later Frederick Douglass. We talked about how sometimes people are killed for what they believe and for standing up for the poor and the oppressed when we remembered Polycarp. We talked about standing up for oneself and for others, even when the powerful disagree with you, when we remembered Martin Luther. We talked about poets, and teachers, and priests, and prophets modern and ancient. We talked about the women and men who lived holy lives. We learned about Christianity together, not through repetition of doctrine or theology or Christology but through seeing it in practice by people like us, our brothers and sisters in faith from all over the world. In fancy terms, we focused on the incarnational rather than the Incarnation.

More than the daily saints, though, my kids loved the idea of patron saints. Both of my boys have saints in their names, so we talked about who those saints were and it gave them a real, personal connection to the whole idea of saints. But, more than their names, they glommed on, as only children can, to the patron of their favorite thing: cats.

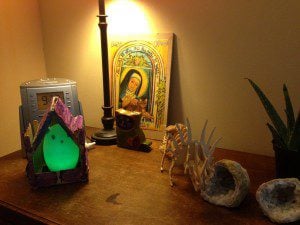

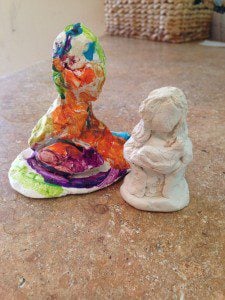

So, that is how my children became obsessed with Dame Julian of Norwich. And that is how our Lenten practice kept going well beyond Easter (the Church remembers Julian on May 8). On Julian’s saint day, we opened up the modeling clay and made our own saint statues of her. We printed out pictures of our favorite saints and Modge-Podged them to thin wooden boards. We read stories about her.

Now if I could only to get them to stop torturing the cat in real life.

But lest you think I have little monks-in-training, I should confess, my kids’ notion of saints and patrons and divines is sometimes a little thin.

One morning, my youngest walked into the kitchen, and with a lopsided grin, announced he was going to be the patron saint of banners. It was utterly and wonderfully nonsensical. This, of course, led to a morning of complete silliness of who could be the patron saint of the oddest thing. I joined right in, declaring myself the patron saint of bubbles, refrigerator magnets, and kitchen sinks. My oldest son interrupted to explain he was going to be the patron saint of poop. He even went so far as to craft his hagiography of how it all was going to happen. I will spare you the details, but honestly, it was the holiest moment of Lent for me.

After 40 days of the saints, Good Friday was finally approaching and I was scheduled to preach (my kids always know when I am preaching because I spend my time walking around the house muttering and gesturing at no one in particular as I practice). It was a few days before my sermon when, for the first time, I sat my boys down and told them the whole Passion story.

And when they heard that Jesus died, they heard it not in the context of their sins, their shortcomings or some cosmic transaction. Rather, they heard it in the context of the saints, many of whom had also died holy deaths. Many of the saints died for how they lived, I explained, just like Jesus died for how he lived. And I reminded them, that in resurrection, death didn’t have the last word, just as death didn’t have the last word with our saints. They live on, and just as we had been communing with the saints all Lent, so too do we commune with Jesus all year in the breaking of the bread.

In retrospect, it strikes me that if we want to subvert certain damaging and pervasive atonement doctrines, one way to do so, and to do so from tradition, is to start with the saints. Because when we start spirituality with the saints, we center Christianity in its practice rather than its beliefs, with the community rather than the individual, with embodied faith at its core instead of a scapegoat.

Now, I would like to say that this was all part of some grand and insightful plan. Because it would make me sound like a very smart, very spiritual, and very intelligent parent.

But really, it was just a happy accident that I stumbled into. But sometimes accidents can be holy as well as happy.

And it made me think that the whole time we were remembering the saints during Lent, maybe, just maybe, the saints really were praying for us as well.