In the theologically conservative church of my childhood, I was asked to believe some fairly paradoxical claims about Jesus: that he was both “fully human and fully divine”—and that he was “the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Hebrews 13:8). The intention of such teachings was to set him apart as special and holy. But it always seemed to be that it set him in another league—not even playing the same sport—as the rest of us. (How impressive is it to be “perfect” if you have unfair advantages?)

As I grew up and studied the historical Jesus more closely, I came to discover that Jesus of Nazareth was indeed fully human, but he was not perfect. And that if there was any sense in which he was “fully divine,” it was in the same way that every human being has the potential to be in touch with the sacred, numinous, and mysterious aspects of existence.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, I have come to find this latter view—of embracing Jesus’s humanity—to be the more challenging perspective. If Jesus (or you may substitute the founder of your religion of choice) is a wholly unique type of god-man, then there are ways that lets the rest of us off the hook. If a historic figure already did the heavy lifting, then all that’s left for us to do is remember, honor, and worship them. In contrast, if the founders of every spiritual and religious movement are regular human beings like the rest of us, then the onus remains on us to imitate, build on, or even improve upon their example.

Along these lines, I read a quote many years ago from Dorothy Day (1897-1980) that has stuck with me. Day, as many of you know, was a social activist known for living in solidarity with the poor in the Catholic Worker houses she helped found. And she would periodically caution her admirers, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” She did not want to be viewed as some special god-woman to whom acts of mercy come naturally and without effort. She did not want us to miss the struggle, the sacrifice—in her words The Long Loneliness—behind her good works.

Relatedly, many people are familiar with what psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875 – 1961) called our shadow: the repressed, unconscious parts of ourselves which nonetheless still affect us. The invitation, as we mature, is to become increasingly conscious of our shadow. Often, however, references to our shadow self focus only on the negative aspects that we repress out of guilt or shame. But Jung also wrote about the golden shadow, which relates to the positive, untapped potential within ourselves.

Just as someone can be particularly triggering to us if negative aspects of their personality are similar to unconscious, repressed aspects of ourselves—so too can we deeply admire someone, perhaps because of some aspect of their personality that triggers unrealized possibilities within ourselves. This insight invites us to reflect, for instance, on why—of all the people in the world—we are each uniquely fascinated with different aspects of the characters of particular people. One reason may be that your subconscious attraction to a certain person is inviting you to experiment with making manifest some hidden aspect of yourself.

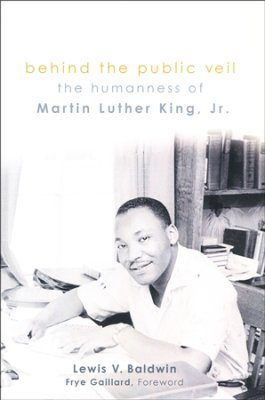

This shadow dynamic plays out not only on the individual level, but also on the level of society at large. And in these days following Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I would like to invite us to reflect on what the notion of the Shadow might have to teach us about honoring Dr. King’s legacy. As the Religious Studies professor Lewis Baldwin has explored in his book, Behind the Public Veil: The Humanness of Martin Luther King Jr. (Fortress Press, 2016), Dr. King is too often “lionized, sanitized, and made larger than life” (ix). So let us pause in the wake of MLK Weekend to remind ourselves that he was fully human, just like the rest of us. And for those of us who admire him, the invitation is not to revere him as a saint, but to discern the ways that we can, within our own spheres of influence, follow his example.

This shadow dynamic plays out not only on the individual level, but also on the level of society at large. And in these days following Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I would like to invite us to reflect on what the notion of the Shadow might have to teach us about honoring Dr. King’s legacy. As the Religious Studies professor Lewis Baldwin has explored in his book, Behind the Public Veil: The Humanness of Martin Luther King Jr. (Fortress Press, 2016), Dr. King is too often “lionized, sanitized, and made larger than life” (ix). So let us pause in the wake of MLK Weekend to remind ourselves that he was fully human, just like the rest of us. And for those of us who admire him, the invitation is not to revere him as a saint, but to discern the ways that we can, within our own spheres of influence, follow his example.

You only have to scratch the surface of Dr. King’s life to learn that although he was a great man, he was not perfect. He struggled with shortcomings—as we all do. A more rounded view comes into focus as you learn more about Dr. King from those closest to him. For instance, his sister—although affectionate in her recollections of Dr. King—also made it clear that, “My brother was no saint” (18). And although there are saintly signs in the stories about King’s childhood —such as that he “refused to play with guns,” even though guns were a very popular childhood toy at that time (20), there was also the time he and his brother “beheaded a number of their sister’s dolls and scattered their body parts throughout the house and in the backyard in the weeds near the fence” (20). So he wasn’t exactly a prodigy of Gandhian nonviolence from birth (21).

In other fascinating signs of his humanity, one of the greatest public speakers in history “made Cs in two public speaking courses his first year” in seminary (44). Dr. King was also known to “smoke cigarettes and consume alcohol in moderation,” which may not seem scandalous today, but as a black Baptist preacher in the South in the 1950s, those were rebellious acts (67).

And in this brief survey of Dr. King’s human imperfections, some of you may be interested in a brief detour of how the parallel humanity and imperfections of my own tradition of Unitarian Universalism fit into the story. In 1951, after graduating seminary, King entered a Ph.D. program in systematic theology at Boston University. And Boston is the historic center of Unitarian Universalism (51). (During the nineteenth-century, the joke is that Unitarianism was about “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Boston.”)

King was not merely geographically proximate to Unitarianism in Boston; he knew the tradition fairly well. Indeed, in 1955, he completed his doctoral dissertation on A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman, the latter of whom was not only a brilliant theologian, but also a Unitarian minister (52). Moreover, my colleague The Rev. Rosemary Bray McNatt, the first African-American President of one of our UU-identity seminaries, was surprised to learn many years ago in an interview with Coretta Scott King that she “went to Unitarian churches for years, even before I met Martin…. And Martin and I went to Unitarian churches when we were in Boston.”

Along these lines, it is not a coincidence that the Unitarian Universalist Association’s Beacon Press has an exclusive partnership with the estate of Dr. King called the “The King Legacy” series, which gives Beacon Press “the sole right to print new editions of previously published King titles and to compile Dr. King’s writings, sermons, orations, lectures, and prayers into entirely new editions, including significant new introductions by leading scholars.” There is a deep resonance between UU Principles, values, and history of activism and the legacy of Dr. King. However, Coretta Scott King continued that although she and Martin seriously considered becoming Unitarian, they realize “We could never build a mass movement of black people if we were Unitarian.”

There is a lot more to be said here that I have addressed in some measure previously. For now, to address a few Unitarian contributions and connections to Dr. King’s legacy, on the one hand there is the example of Unitarian forebears—some of whom are still alive today—who showed up in impressive numbers in 1965 in response to Dr. King’s call to join in the Selma to Montgomery March. On the other hand, a few years later in 1968 and 1969, the Black Empowerment Controversy (or “White Power Controversy,” depending on whom you talk to) erupted in our association over the funding of the Black Affairs Council. The Black Lives of UU movement today is seeking to lead us toward ways of healing the wounds left by the UU movement’s failure to fully live into the work of dismantling racism over the past few decades.

Returning our focus to King, there is another angle that is important to wrestle with in reflecting on the “golden shadow” of how Dr. King’s legacy calls us to live into our own untapped potential. In reflecting on how we—individually and collectively—may feel led to follow King’s example of acting for peace and justice, we need to be honest that his work for racial and economic justice came at a high cost to his family.

Regarding family life, there were ways in which Dr. King had progressive views toward women for his time. (Keep in mind that he was killed prior to the Second-wave Feminism of the 1970s.) For example, the traditional bridal promise to “obey” was left out of their wedding vows (86). And in 1958 his first book Stride toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story was dedicated to “Coretta, my beloved wife and co-worker” (93). At the same time, Dr. King’s level of activism meant that he was almost never home, which frequently meant missing birthdays and other special occasions (105). To be specific, in the last few years of his life, after he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, he “was at home only about ten percent of the time” (108).

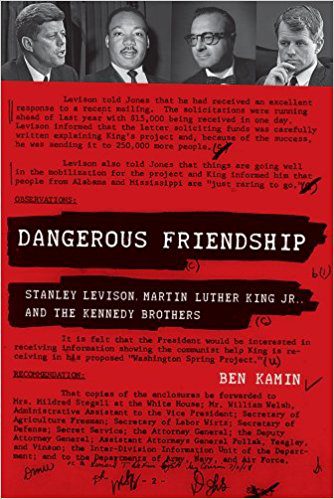

Now, in exploring Dr. King’s humanity, I would be remiss if I failed to mention his sexual infidelity. But let me hasten to add that it has always bothered me that King’s affairs are too often mentioned in a scandalous light outside of any context; so allow me to add some important details that are often neglected, using as a guide Ben Kamin’s important book Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers (Michigan State University Press, 2014).

Now, in exploring Dr. King’s humanity, I would be remiss if I failed to mention his sexual infidelity. But let me hasten to add that it has always bothered me that King’s affairs are too often mentioned in a scandalous light outside of any context; so allow me to add some important details that are often neglected, using as a guide Ben Kamin’s important book Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers (Michigan State University Press, 2014).

It’s fascinating, for instance, that King’s affairs were initially discovered because the FBI was surveilling not King himself, but Stanley Levison, a northern Jewish ally of King (6). Levison had been a Marxist in his younger days, but had “severed all ties to the Communist Party in 1956,” prior to meeting King—although the FBI repeatedly tried and failed to prove otherwise about both Levison and King.

To tell you just a little bit about Levison, he was a socialist who got rich from capitalism. And he was a powerful friend for Dr. King. The discussions in 1959 that led to Dr. King and other prominent African-American ministers founding the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) began in the New York City kitchen of Stanley Levison (13). In 1963,

Levison quietly underwrote the Montgomery Improvement Association, of which the 26-year-old King was elected President in 1955.” And over the years, Levison “drafted articles and speeches for King, prepared his tax returns, and kept the coffers of the SCLC from drying up. In 1958, he completed and edited King’s first book, Stride toward Freedom. He negotiated the publishing deal for King with Harper & Brothers. (16)

And although Levison steadfastly refused payment for any of his services, the cost for those services came high. “What King did pay for, in a broader sense, was Levison’s indisputable association with Communists in the 1940s and early 1950s” (46).

As I said, the related surveillance, led to the FBI discovering King’s affairs. But here’s the thing, if someone is going there: the reason President John F. Kennedy pressured Dr. King to distance himself from Levison is that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had an agenda against King—and even more so against Levison. And Kennedy worried that helping King might cause Hoover to “retaliate with the release of information about the president’s unrelenting womanizing”(12). At this point, many women may be thinking #MeToo.

(But wait! There’s more!) Speaking of our shadow sides—and the ways those repressed sexual aspects of ourselves can emerge in twisted ways—another ironic layer to this story is that part of what drove Hoover’s obsession with wiretapping other people’s sexual escapades was his alleged repressed shame about his own cross dressing. There is, of course, nothing wrong with gender-bending, except when you are hypocritically persecuting other people for the sexual and gender freedom and acceptance that you know, deep down, you desperately long for—for yourself (17). There’s a lot more to say about all that as well, but surely that’s enough armchair psychoanalysis for one post.

My overall point is that none of us—from our greatest heroes to our cruelest villains—are ever anything less than fully, messily, and complexly human. And in the words of the Civil Rights activist Andrew Young (1932-) who later become Mayor of Atlanta, “Martin didn’t need us to [deify him]. He needed us to help him” (Baldwin 321). For King, Stanley Levison represented a “dangerous friendship”: a powerful, transformative, life-changing friendship, but one that did not come without a cost. And if we are honest about all of who Dr. King was—including how radical he was for the cause of peace and justice—then we can see that he is in many ways a dangerous friend for us to have today: dangerous in never being content with any unjust status quo. A dangerous and risky friend to have—but also powerful, transformative, and life-changing.

Indeed, Dr. King was tragically murdered because his activism was a threat to highly-profitable systemic injustices in our society. And we are now approaching the 50th anniversary of his assassination on April 4, 1968. He was only thirty-nine, the same age I am today. If he were still alive, tomorrow would be his eighty-ninth birthday. He should be with us today as an elder in the movement for racial justice. And so, in memory of the tremendous legacy he left behind, may we be increasingly conscious and committed to turning Dr. King’s dream into deeds. Together, let us build the world we dream about: a world of Collective Liberation, with economic, racial, and gender justice—not merely for some, but for all.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles