In the book Learning to Be White, the Unitarian Universalist minister and scholar Thandeka writes that, “No one is born white in America” (vii). For many people in the U.S., that claim likely feels either counter-intuitive or perhaps even nonsensical. Elaborating on her view in a later anthology called Soul Work, she writes that although no one is born white,

children are born with an innate ability to relate and bond to others…. Children thus have to learn how to internally destroy their own ability to relate and bond with those who are not acceptable to their parents or authority figures. Only then can they learn to deny what their feelings affirm: the importance of openhearted engagement with others. (132-133)

The cold-heartedness required to “learn to be white” is part of what allows adults in our society to tolerate, for example, a Prison Industrial Complex that is massively biased against people with black or brown skin. (For more, see my previous post on “The New Jim Crow.”)

Growing up, I can remember multiple ways in which I was taught both implicitly and explicitly that blacks and whites were different. (Can you recall episodes in your life of “learning to be white” or “black” or “brown”?) I can remember, for example, my budding friendship with a young black girl my own age being discouraged because “Birds of a feather fly together.” I wasn’t born “white,” but I quickly learned to be white — in a way that was about far more than noticing the color of my skin.

Indeed, the problem is not that “Kids Say the Darndest Things.” Of course young children will sometimes ask, “Mom, why is her skin so light?” Or, “Dad, why is his hair different than mine?” The problem is not children’s natural curiosity about genuine differences of appearance. Instead, the problem — a problem rotting at the core of our society — is the choice to continue passing down, generation to generation, cruel lies about skin color representing anything more than superficial differences between human beings, who are in truth all members of the same extended family.

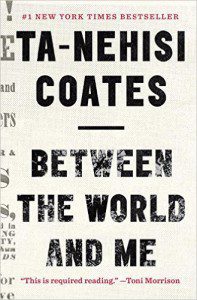

And one of the reasons that I have been encouraging everyone I know to read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s important  new book Between the World and Me is that he extends Thandeka’s point in a deeply moving and personal way that also connects with the current #BlackLivesMatter movement. In reading Coates’s book, one of the many points that I found myself wrestling with was his use of the phrase “people who believe they are white.” Coates expands on this claim when he writes that even if we stopped teaching lies about skin color being anything more than a superficial difference, there would nevertheless,

new book Between the World and Me is that he extends Thandeka’s point in a deeply moving and personal way that also connects with the current #BlackLivesMatter movement. In reading Coates’s book, one of the many points that I found myself wrestling with was his use of the phrase “people who believe they are white.” Coates expands on this claim when he writes that even if we stopped teaching lies about skin color being anything more than a superficial difference, there would nevertheless,

surely always be people with straight hair and blue eyes, as there have been for all history. But some of these straight-haired people with blue eyes have been “black.”… Virginia planters obsessed with enslaving as many Americans as possible are the ones who came up with a one-drop rule that separated the “white” from the “black,” even if meant that their own blue-eyed sons would live under the lash. (42)

The way our society is structured around race, in other words, resulted from a cruel and arbitrary set of historical circumstances.

Reflecting on this history, Coates’s book is written as a letter to his 14-year-old son about what it is like to grow up black in America. It is inspired by James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, another slim, but incendiary volume written as a letter, in that case to Baldwin’s 14-year-old nephew about the struggle of being black in America, published in 1963 on the 100th anniversary of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Coates’s phrase “people who believe they are white” is likewise borrowed from James Baldwin’s essay “On Being White and Other Lies.”

The following passage from Baldwin will give you a taste of where Coates found the courage to write so boldly. Baldwin writes:

By deciding that they were white…. By persuading themselves that a Black child’s life meant nothing compared with a white child’s life…. By informing their children that Black women, Black men and Black children had no human integrity that those who call themselves white were bound to respect. And in this debasement and definition of Black people, they debased and defamed themselves. And have brought humanity to the edge of oblivion: because they think they are white. Because they think they are white, they do not dare confront the ravage and the lie of their history. Because they think they are white, they cannot allow themselves to be tormented by the suspicion that all men are brothers. Because they think they are white, they are looking for…stable populations, cheerful natives and cheap labor…. White being, absolutely, a moral choice (for there are no white people).

Baldwin confronts us with the truth that “learning to be white” is an ethical choice, not a biological destiny.

Along these lines, you may recall media reports on “A.J. Jacobs and the World’s Largest Family Reunion” about a growing movement of people using the Internet to build incredibly expansive family trees: “Familysearch.org, for example, has stitched together tens of thousands of user-contributed family trees from around the world. The single-largest tree contains 240 million people.” Using this data, bestselling author A.J. Jacobs was able to wheedle his way into a phone conversation with former President George H.W. Bush. Jacobs told Bush’s representative that he was a “long-lost cousin” — and he is, just a lot less close a cousin that we are accustomed to recognizing: “Mr. Jacobs and the 41st president can be found 21 genealogical steps from each other, through marriage, on interlocking family trees….” Using the “long-lost cousins” line, Jacobs was also able to get in touch with Daniel Radcliffe (they’re 29th cousins) and Ludacris (they are 39th cousins).” Jacobs is also a distant cousin of the singer John Legend. And that is the point at which these huge family trees become particularly relevant to our topic: Jacobs is what Coates would call “people who think they are white” and Ludacris and John Legend are what we could call “ people who think they are black,” but it turns out they — and all of us humans beings — are all closely related cousins.

Relatedly, some of you may recall headlines from more than a decade ago from the journal Science about DNA research, which has revealed that,

populations from different parts of the world share even more genetic similarities than previously assumed. All humans are 99.9 percent identical and, of that tiny 0.1 percent difference, 94 percent of the variation is among individuals from the same populations and only 6 percent between individuals from different populations.

Moreover, a year after those headlines that, “All humans are 99.9% identical” at the DNA level, some of you may recall the three-part PBS series with the important title “Race: The Power of an Illusion.” The upshot is that the biological sciences agree with Thandeka that “No one is born white in America.” We’re all on relatively closely-connected branches on the same worldwide family tree. But for historically-contingent circumstances related to power and greed, colonialism and slavery, we have learned to be “white” and “black” and “brown” and “yellow” — and various combinations in between.

Expanding our view even further, in the years since 2002 discovery that “All humans are 99.9 percent identical” at the DNA level, further studies have shown that there is only a 1.23 percent difference between Homo sapiens and Pan troglodytes, popularly known as chimpanzees:

Chimps make and use simple tools, hunt in groups and engage in aggressive, violent acts. They are social creatures that appear to be capable of empathy, altruism, self-awareness, cooperation in problem solving and learning through example and experience. Chimps even outperform humans in some memory tasks.

After Darwin, we know that not only are all human beings incredibly closely related at the DNA-level, but also our species is also much more closely related and interdependent with the other life forms and larger ecosystems of this planet than is often realized.

And perhaps this perspective can help us more fully appreciate studies that have shown that,

The human species is so evolutionarily young, and its migratory patterns so wide [and] restless, that it has simply not had a chance to divide itself into separate biological groups or “races’” in any but the most superficial ways. “Race is a social concept, not a scientific one…. We all evolved in the last 100,000 years from the same small number of tribes that migrated out of Africa and colonized the world….” There is only one race — the human race.

But despite what science tells us about the universal kinship of all human beings, there are powerful forces in our world perpetuating the illusion that “racial” differences are more than skin deep. Indeed, the best analogy I have heard recently for explaining that racism is a social construction is that racism is “real in the same way that Wednesday is real. But it’s also made up in the same way that Wednesday is made up.” In Coates’s turn of phrase, “Race is the child of racism, not the father” (3). Or as your high school biology teacher might have explained it: the myths of racism confuse Phenotype (observable, superficial differences like skin color, hair, facial features, etc.) with Genotype (one’s hereditary DNA). The truth is that one can infer almost nothing from a person’s skin color (part of the superficial Phenotype) about that person’s genetic code (the vastly more important Genotype).

Although I do not have time to trace the full history of racism as a social construction, books such as George M. Fredrickson’s Racism: A Short History (Princeton University Press, 2003) demonstrate that looking back to the ancient Greco-Roman world, which includes early Christianity, racism as we know it did not exist. Rather, there were “slaves representing all the colors and nationalities…[and] corresponding diversity from among those who were free” (17). Racism as we have come to know it today is of quite recent origin, historically speaking. Consider, for instance, how quickly the social construction of race has changed when we remember that “it was not uncommon in the 19th century for the English and Americans to regard the Irish as ‘black,’ and for Italians to have an ambiguous status between white and black in the U.S.” But today Jewish, Italian, and Irish immigrants to this county are “people who believed themselves to be white.” They have “learned” — they have been pressured to socialize — into being “white.”

In Coates’s words,

Americans believe in the reality of ‘race’ as a defined, indubitable feature of the natural world…. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the preeminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes, which are indelible — this is the new idea at the heart of these new people who have been brought up hopefully, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white. (7)

The call is to tell different stories that tell the truth of our common humanity.

That being said, I do not agree with the argument of Chief Justice John Roberts that “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Such positions seek to avoid taking responsibility for the consequences of our country’s long history of racial bias. Instead, I agree with former Justice Harry Blackmun who said that, “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently,” through programs such as Affirmative Action, at least for quite some time to come (Fredrickson 143). Coates goes farther in making “The Case for Reparations.”

I will conclude with these words from Dr. Cornel West’s Ware Lecture at this year’s UU General Assembly. Dr. West said,

if we’re serious about the analysis from ecological catastrophe all the way across to moral and spiritual and political and economic catastrophes, then we’re going to have to choose to be a blues people.… Because terrorism, and trauma, and stigma is not new for some of us. Catastrophe is not new. There has never been a Negro problem in America. There has been catastrophes visited on black people….. There’s never been a woman’s problem. Catastrophe has been visited on women. There’s never been an indigenous people’s problem. Catastrophes visited on indigenous peoples. There’s never been a gay problem and a lesbian problem. Catastrophes have been visited on gays and lesbians. There’s never been a disability problem. Catastrophe visited on — that’s the blues perspective. That’s the blues perspective, and we just lost the king of the blues, BB King, and what did he say? Nobody loves me but my mama, and she might be jiving, too. That’s the blues. But B.B. King says in the face of the blues, I’m still aspiring to integrity, honesty, decency, and virtue.… America, do we have what it takes? Always an open question. It could be we just experience the decline of an empire that goes the same way of Rome. Depends on what we do….

For Further Study

Racism: A Very Short Introduction by Ali Rattansi (Oxford University Press, 2007)

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration”

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles