This year marks one hundred years since the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, popularly known as the Johnson-Reed Act. Reflecting the nativism, xenophobia, and scientific racism of the early twentieth century, this law drastically reduced immigration to the United States, excluded non-white immigrants who were racially ineligible for citizenship, and created a permanent national origins quota system that prioritized immigrants from northern and western Europe. In creating these new discriminatory barriers to immigration, the Johnson-Reed Act transformed the racial and ethnic demographics of the United States for the next four decades.

When discussing the Johnson-Reed Act, immigration historians have typically focused on how this law was the culmination of the racism and nativism of its era. However, what is less appreciated is the degree to which the Johnson-Reed Act limited not only racial and ethnic diversity but also religious diversity, reflecting the religious politics of the United States in the early twentieth century and the broader history of Protestant Christians seeking to make the United States a nation of and for Protestant Christians. Put simply, the Johnson-Reed Act functioned as an instrument of religious restriction and exclusion. In so doing, it advanced aspirations of building a Protestant nation.

The Johnson-Reed Act

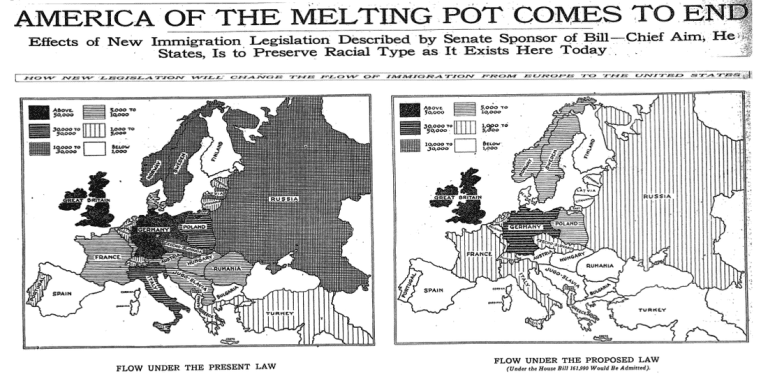

The Johnson-Reed Act had several components. First, it imposed an overall ceiling on immigration: 185,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere each year. (There were no numerical restrictions on immigrants from the Western Hemisphere.)

Second, building on the quota system created by the 1921 Emergency Quota Act, the Johnson-Reed Act created a new and permanent system of national origins quotas that limited the number of immigrants who could legally migrate from each country. Congress set these quotas at 2% of the immigrant population from that country as counted in the 1890 U.S. census. The decision by lawmakers to base quotas on the 1890 census was important and intentional. Significant numbers of immigrants had migrated to the United States from eastern and southern Europe in the three decades after 1890, and the decision to base the quotas on the makeup of the U.S. population before the arrival of these immigrants reduced the the quota for eastern and southern European immigrants.

Finally, the Johnson-Reed Act upheld the Asiatic Barred Zone, which was introduced in 1917 and barred immigration from much of Asia. In addition, it excluded all immigrants who were ineligible for citizenship. This aspect of the law was especially relevant to potential immigrants from Asia. The 1790 Naturalization Act restricted naturalization to white individuals, and recent Supreme Court decisions—namely, the Ozawa case in 1922 and the Thind Case in 1923—deemed people of Asian descent to be legally non-white and thus ineligible to become citizens. The Johnson-Reed Act, informed by these recent legal developments, prevented the migration of Asian people on the basis that they were racially ineligible for citizenship. (Note: the racial requirement for citizenship was in place until the McCarran-Walter Act removed it in 1952.)

Protestant Christian Responses to the Johnson-Reed Act

How did Protestant Christians respond to the Johnson-Reed Act and the broader push for immigration restriction and exclusion? As the historian Nicholas Pruitt argued in Open Hearts, Closed Doors, their response was mixed. On one hand, some Protestant leaders opposed the Johnson-Reed Act because it called specifically for the exclusion of Japanese immigrants. Pointing to statements issued by the Federal Council of Church’s Commission on Relations with the Orient, Pruitt described how the law’s treatment of Japanese immigrants compelled some American Protestants to oppose the law on missional and diplomatic grounds:

First, Protestants remained concerned that the law would have a deleterious effect on home and foreign missions…Second, the principle of the brotherhood of man inspired many liberal-minded Protestants to espouse international harmony and oppose racial discrimination. Proponents of this principle believed the legislation violated this ideal by singling out Japanese for exclusion and disregarding the sovereignty of Japan. Finally, those who criticized the 1924 legislation because of its treatment of Japanese immigration feared that Japan might pose a threat to international peace (51).

According to Pruitt, after Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, several American Protestant organizations—the Federal Council of Churches, for example, along with denominations such as the Southern Baptists—continued to publicly criticize how the law treated people from China and Japan.

In general, though, American Protestants favored immigration restrictions and supported both the Johnson-Reed Act and its precursor, the 1921 Emergency Quota Act. “While mainline Protestant leaders opposed outright racial discrimination toward Japanese, they did not attack the prejudice toward southern and eastern Europeans in the quotas established in 1924,” wrote Pruitt. “This suggests Protestants generally believed restriction across the board was necessary, and were only willing to offer resistance when certain nationalities were targeted for outright exclusion” (53). Importantly, the religious backgrounds of the southern and eastern Europeans who had immigrated to the United States in the quarter century leading up to the Johnson-Reed Act contributed to Protestant support for the quota system. “For many American Protestants the total immigration during the last several decades was staggering,” Pruitt wrote, “and the predominantly Catholic and Jewish backgrounds of many of these immigrants did not set Protestant minds at ease” (53).

Thus, while some American Protestants publicly criticized the exclusion of Japanese immigrants, others wrote openly about their support for immigration quotas that limited immigration from southern and eastern Europe, the parts of the continent that had significant populations of Catholics, Jews, and Orthodox Christians. For example, in 1923, the southern Methodist publication Missionary Voice published an editorial that declared that “[I]mmigrants settled this country and established this Government but they were immigrants from Northern and Western Europe.” The authors of the editorial cautioned that unrestricted immigration from other parts of the world harm the nation. “If the gates are opened and the tides of immigration permitted to run at full height nothing can save our cherished institutions and customs,” they said (qtd. in Pruitt 49).

The Repercussions of Restriction and Exclusion

Whether or not Protestant Christians supported or opposed the Johnson-Reed Act, this much is true: the law had an enormous impact on the ethnic, racial, and religious demographics of the people who immigrated to the United States in the coming four decades. The first fundamental change was that the number of immigrants who entered the United States after 1924 dropped substantially. Moreover, the composition of the immigrant population changed. In the first five years of the new system, the vast majority of immigrants entering the United States hailed from Great Britain, Ireland, and Germany. The barriers to entering the United States from other parts of the world were formidable. As the historian Aristide Zolberg estimated in A Nation by Design, for every northern or western European immigrant granted a visa, three were denied due to a maxed-out quota. In contrast, for each immigrant admitted from a country in southern, central, or eastern Europe or the Middle East, seventy-eight were denied (264).

Significantly, the regions of the world that were allocated the largest quotas were those that were home to people deemed racially and religiously desirable in the eyes of the crafters of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act. In contrast, the countries assigned the smallest quotas had populations that were predominantly Catholic, Jewish, Orthodox, and Muslim, and outright barred migration from Asia, which was home to Buddhist, Muslim, and Hindu populations. In this way, the Johnson-Reed Act, while not explicitly restricting or excluding groups on the basis of religion, nevertheless created a system that heavily favored Christian immigrants, especially Protestant immigrants. As Khyati Joshi argued in White Christian Privilege, the restrictionist legislation of 1921 and 1924 were efforts to “make America Protestant again” and “rewind the clock and restore White Protestantism’s flagging demographic disadvantage” (98).

The religious dimensions of the Johnson-Reed Act are worth considering in the current moment, and not simply because this piece of legislation was passed one hundred years ago. In 2024, as in 1924, Americans are once again embroiled in fierce debates about immigration policy, and these debates often overlap with religious identities, ideologies, and aspirations for the nation. Take, for example, recent research on Christian nationalism. According to the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), 71 percent of people who adhere to Christian nationalism agree with the “replacement theory,” which holds that immigrants are “invading our country and replacing our cultural and ethnic background.” Among white people who sympathize with or adhere to Christian nationalism, that number rises to 81 percent.

As we make sense of contemporary immigration debates and the threads of xenophobia and nativism that run through it, we must situate these conversations in American religious history and consider how religion shapes both public attitudes about immigration and immigration policy itself. Most significantly, it shapes who we are as Americans.