Britain during the 1960s and 1970s suffered from a Prime Minister named Harold Wilson. Once, when Wilson was to read the lesson at Westminster Abbey, the clergy involved asked him which version of the Bible he would like to use – King James, Revised, which one? Flustered, Wilson replied that he would read from the Word of God. We should sympathize with his problem. When we say that the Bible is the Word of God, it surely helps to ask which Bible we are talking about.

Around the world, the canon of the Bible varies substantially, somewhat in the New Testament, and to a much larger extent in the Old. Many Christians around the world – a sizable majority in fact – know a Bible lengthier than that of American Protestants. As I suggested in a recent column about the Bible as the source of authority for Protestants, that fact surely raises serious issues. Above all, we need to be careful about defining the exact limits and boundaries of the Bible and the books it contains, which is not as obvious as we might think. I’ll illustrate this point by substantially expanding a couple of columns that I published at this site several years ago.

The Limits of Scripture

Of all the world’s churches, the one with the canon that differs most radically from the standard US Protestant version is Ethiopia’s truly ancient Tewahedo Church, which commands the loyalty of some 45 million people. This is rather more than the number of all US Baptists of all denominations combined. Among many other distinctive features, the Tewahedo Old Testament includes 1 Enoch and Jubilees – both truly bizarre works by the standards of mainline Western Christianity (although the author of the canonical New Testament Epistle of Jude likewise regarded 1 Enoch as scripture).

But we don’t have to travel to Africa or the Middle East to find quite different concepts of the Biblical canon. Today’s Protestant Bible would seem remarkably short to many Christians around the world, and indeed to past Protestant generations. Several books have dropped out of memory in fairly recent times, and some of them really do deserve to be known and appreciated much more widely.

The Second Canon

The main difference involves the so-called Second Canon, the Deuterocanonical books. As used in the Roman Catholic Church, these include such texts as Judith, Tobit, Wisdom, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), 1 and 2 Maccabees, Baruch, and some additional passages in Daniel, including the story of Susanna. These works were not formally included in the Hebrew Bible as fully canonical, although fragments of Sirach and Tobit were both found at Qumran, pointing to their Hebrew language origins. Ironically, the earliest guide we have to the Hebrew Bible canon is in Sirach itself (chs. 44-50).

These works did appear together in the Septuagint. As a reminder, this was a third century BC translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, which differs from the original text at many points. Normally, we might ask why we would ever prefer a translation to the original, but in this instance, the translation preserves older textual readings, as well as older attitudes to the contents of scripture. Crucially for Christian history and Bible interpretation, the early church read its Old Testament in the Septuagint.

Different churches had accepted this Second Canon from the early Christian centuries. The great early Bible codices such as Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus naturally included the works of the Second Canon, and overwhelmingly, this was the Bible text known to the Church Fathers. Augustine was one of many who happily listed them all as part of the canon. He noted that

two books, one called Wisdom and the other Ecclesiasticus, are ascribed to Solomon from a certain resemblance of style, but the most likely opinion is that they were written by Jesus the son of Sirach. Still they are to be reckoned among the prophetical books, since they have attained recognition as being authoritative.

He was a particular fan of Wisdom, in which “the Passion of Christ is most openly prophesied.” (In the second century, the Muratorian Fragment suggests that the Roman church not only regarded Wisdom as canonical, but that they included the work in the New Testament, rather than the Old). Augustine listed some of the books as puzzling or oddly placed, but no more so than others that we accept today as wholly canonical:

There are other books which seem to follow no regular order, and are connected neither with the order of the preceding books nor with one another, such as Job, and Tobias, and Esther, and Judith, and the two books of Maccabees, and the two of Ezra [ie Ezra and Nehemiah], which last look more like a sequel to the continuous regular history which terminates with the books of Kings and Chronicles.

Occasionally, some scholars would protest against the inclusion of the “Deuteros” in the Christian canon – Jerome was hostile. But these critics admitted that they were in a small minority, and the church’s overwhelming consensus won out over time. Even medieval proto-Protestants like the Waldensians not only accepted and read these books, but treated them as among their favorite sections of the Bible. They loved stories like Maccabees and Tobit, and venerated the main characters as Christian role-models.

Modern Western Protestants may well have heard of these books, and think of them under the general title of “apocrypha,” at best an inferior and also-ran category of scripture. For most non-Protestant churches around the world, though, they are not apocryphal, but fully accredited components of the canon, which are read in the liturgy. They are definitively Bible. This is true of the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, as well as Oriental Orthodox, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian. If such matters were ever to be decided by raw numbers of Christians worldwide, then the Deuterocanon would win by something like a three to one margin. The Roman Catholic Church alone, by far the world’s single largest religious body, accounts for some 55 percent of Christians.

The Protestant Canon

Just how Protestants came to lose these books is a curious story. Up to the Reformation, there was no real question about the acceptance of those extra books. Reformation-era debates over the Bible naturally focused on issues of canon. The Reformers naturally held to the most stringent standards of inclusion, which usually meant accepting the familiar Jewish definition of the Hebrew Bible. In fairness, let me add that some sixteenth century Catholics also placed the Deuterocanonicals in an inferior or apocryphal position, but after some disagreement at the Council of Trent, Catholics fully accepted the Deuterocanon, a term coined in the 1560s by Sixtus of Siena. Although historical interpretations decided the two positions, Catholics also favored books favorable to their theology, and Protestants accordingly disliked these same works. One text in Maccabees, for instance, supports the idea of prayers for the dead.

But excluding books from the Protestant canon certainly did not mean abandoning them overnight. Most early Protestant Bibles did indeed include the “Deuteros,” but segregated in a special section of apocrypha, sandwiched between the Old and New Testaments. This was the solution of Luther (1534) and it was followed by the Geneva Bible, the standard English text for most mainstream Anglicans and Puritans alike for a century after its publication in 1560. It was many years before the King James overtook it in popularity.

Protestant authorities were careful to stress that these books should not be taken as fully authoritative. In 1563, for instance, the 39 Articles of the Church of England listed these “other Books (as [Jerome] saith) [that] the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.” The Westminster Confession of Faith in 1647 was tougher still, declaring that “The books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the Canon of Scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be any otherwise approved, or made use of, than other human writings.”

Still the Bible

Even so, these texts were included in Bibles and were presented in exactly the same manner as the canonical books, in similar typeface and appearance. The books continued to have authority and religious significance, and the stories they told remained widely known. I could give countless examples, but let me take one English moment. In 1746, the Duke of Cumberland returned to London after bloodily defeating the Jacobite rebellion, which drew heavily on Catholic support. Handel composed an oratorio for the occasion, and naturally turned to the Bible for an appropriate story of a heroic general fighting for his nation and faith against a pagan foe. Also, the story had to be a famous piece well known to a Protestant audience. Where else would he turn, then, but to the story of Judas Maccabeus? Patriots of the American Revolution loved the story of Maccabees.

English-speaking Protestants lost the Deuterocanon not through any calculated theological decision, but through publishing accident, and at quite a recent date. Prior to the early nineteenth century, Anglo-American Bibles included the apocryphal section, but this dropped out as printers sought to produce more and cheaper editions. Increasingly too, during the nineteenth century, anti-Catholic sentiment encouraged Protestants to draw a sharp line between the two variant Bibles. If Catholics esteemed books like Maccabees and Wisdom, there must be something terribly wrong with them. In the nineteenth century US, the right to use particular Bibles – Catholic or Protestant – was one of the major forces driving Catholics to create their own parochial school system, independent of the public schools. That supposed “rejection” of the Bible in turn further fueled popular anti-Catholicism.

As I have noted elsewhere, the sudden loss of those books had unexpected consequences: “That timing meant that when Protestant missionaries set out for Africa and Asia, the Apocrypha did not feature in the Bibles they carried with them, and those texts never had much impact on emerging churches. Over time, though, new converts compared notes, and some were startled to find the disparity between Protestant and Catholic Bibles. On occasion, those converts became suspicious about the explanations that missionaries offered for the differences. Some asked whether their pastors were keeping whole parts of the Bible secret, presumably for their own selfish ends.”

For whatever reason, then, Protestants over the past century have tended not to know these Deuterocanonical works. Not only is the OT apocrypha missing from modern Protestant versions – above all, the New International Version – it is not even a ghostly presence, in the form of an explanatory note. I have one NIV Study Bible that offers a couple of dismissive lines on why these books are missing. Seemingly, they contribute nothing to what we learn from the rest of scripture, and are historically wildly inaccurate – in contrast, say, to the still-canonical (and highly dubious) Esther.

These stories, then, have vanished from consciousness. Although modern Protestants likely know the Maccabean story, it is almost always in the Jewish context, in terms of the origins of Hanukah. This is a critical distinction. Although Christians fully acknowledge the Jewish dimensions of (for instance) the Exodus, or the Exile in Babylon, these stories have been fully integrated into the Christian narrative. Maccabees, in contrast, is now viewed as a Jewish scripture, and no longer part of “our” Bible.

The situation is Orwellian. Not only have these books dropped out of Bibles in which they once were included, but it’s as if they had never existed in the first place.

The Second Canon in Culture

This Protestant amnesia is a real misfortune. Such books as Judith, Tobit and Maccabees offer some real treasures, and they cry out to be rediscovered. One excellent argument is the astonishing influence that these books have had on Christian writers and artists. If we do not know the books, we miss the meaning of a great deal of Christian art and literature.

To begin with a minor example, Milton’s Paradise Lost describes Satan’s reaction to the atmosphere of Paradise. He was

Better pleased than Asmodeus with the fishy fume

That drove him, though enamoured, from the spouse

Of Tobit’s son, and with a vengeance sent

From Media post to Egypt, there fast bound.

The story is from Tobit. Sarah, daughter of Raguel, is accursed. Seven times she has married, and each time, the demon Asmodeus intervenes to kill the husband. Her final desperate attempt is marrying Tobias, son of Tobit. The angel Raphael instructs him to drive off the demon by burning the heart and liver of a fish, which finally forces Asmodeus to flee. Milton, the arch-Puritan, knew the story, and expected his Puritanically inclined readers to do likewise.

In that particular case, not knowing the story scarcely represents a cultural abyss, but matters are different in the visual arts. For several centuries, the Deuterocanonical books gave generations of artists some of their most popular themes. Copyright issues make it impossible for me to reproduce too many images here, but let me suggest a simple project. Go to Google Images, and feed in any of the following three search terms:

Tobias and the Angel

You will be amazed by the number of paintings that appear, by the long time span that they cover, and by the range of first rate artists that have treated these subjects.

Heroic Women

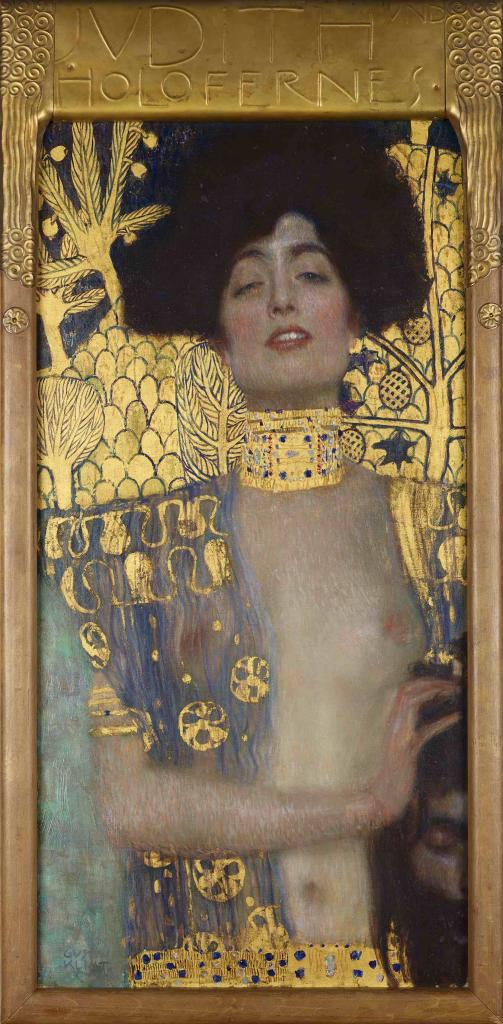

Take for instance the gruesome story of Judith, who saves her country by entering the tent of the enemy general Holofernes and decapitating him while he sleeps. A non-exhaustive list of the painters who have covered the legend would include Michelangelo, Botticelli, Mantegna, Giorgione, Rembrandt, Rubens, Caravaggio, Goya, Klimt, and Jerome Witkin. And that takes no account of stained glass portrayals, or of Donatello’s sculpture. As to literature, the Judith story features in Chaucer and Dante. William Shakespeare had three children: Judith, Susanna, and Hamnet (he admired strong women).

In fact, these three stories have provided the theme for more significant paintings than the great majority of more familiar Old Testament texts. This is scarcely surprising, as between them they cover those three powerful artistic themes, of lust, violence and religion. Susanna especially gave painters and patrons the opportunity to present sumptuous nude imagery, with a titillating element of voyeurism. Even in the 1930s, Thomas Hart Benton’s depiction was so explicit as to be controversial. Meanwhile, Judith’s victory was so gory that even today it would arouse qualms if it featured in a particularly bloody video game.

Before you consign most of this art to the realm of male fantasy and soft porn, do recall that some of the finest paintings of both Judith and Susanna were by Artemisia Gentileschi, the greatest woman painter of seventeenth century Europe. She used the stories magnificently to explore diverse images of womanhood, as both victim and avenger – themes that had special relevance to her personally as a victim of rape. She features prominently in a terrific article in a recent edition of the Nation, on “A Hidden History of Europe’s Pre-Modernist Women Artists.” Judith and Holofernes supply the main illustration. Incidentally, Artemisia Gentileschi features in the news media these days with surprising frequency, and often in the context of that same painting. There is now some debate about how she got to be so good at depicting spurting blood in such precise and accurate clinical detail. One highly plausible theory holds that she learned all about it from chatting to a learned neighbor of hers, some guy called Galileo who dabbled in scientific stuff.

I repeat: when artists and patrons created these pictures, they saw them as indisputably Biblical works, not “apocryphal” in any sense.

As cultural sources, these books are enormously important, but their significance for Christian history and theology is actually even greater. If you want to understand the Jewish world as it developed between about 300BC and 50 AD – the world from which Christianity emerged – then you have no option but to explore texts like Wisdom, Sirach, and Maccabees. As I discussed in my 2017 book Crucible of Faith: The Ancient Revolution That Made Our Modern Religious World, that is where you can trace the themes and concepts that emerge fully formed in the New Testament, including the prehistory of Christology. If we don’t read the Second Canon – if we follow the familiar Protestant Bible – then we seem to have a puzzling gap of some four hundred years between Old and New Testaments, a divine silence. The Second Canon closes that gulf.

In summary: which Bible are we talking about?