The British Guardian just published a really excellent essay that should be required reading for anyone interested in the future of Global/World Christianity, and indeed for the world’s religious futures. It’s by Howard W. French, and it’s called “Megalopolis: How Coastal West Africa Will Shape The Coming Century”. I am guessing this is an extract from a future book.

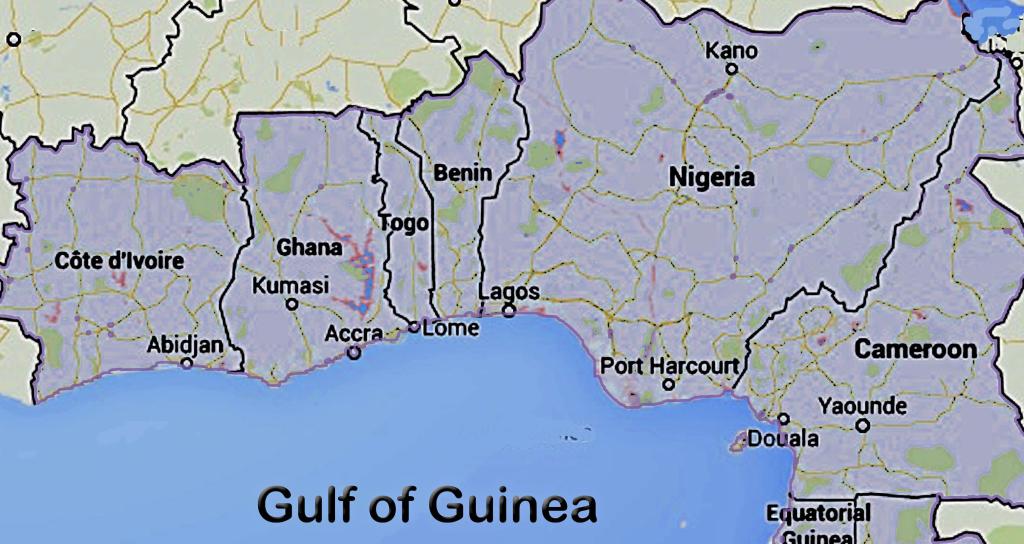

The article focuses on the stretch of coast between roughly Lagos and Abidjan, which incorporates portions of the five countries of Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire. The whole stretch is about 600 miles. French’s central point, which is irrefutable, is that this region is set for explosive urbanization, which will make it one of the world’s most densely packed centers of population:

The projected population for this coastal zone will reach 51 million people by 2035, roughly as many people as the north-eastern corridor of the US counted when it first came to be considered a megalopolis. … By 2100, the Lagos-Abidjan stretch is projected to be the largest zone of continuous, dense habitation on earth, with something in the order of half a billion people.

A half-billion… and do note, crucially, that does not even include the rest of Nigeria. Let me just say that the projected numbers seem a bit high by my calculation, but even if they are off by a hundred million or so, they are still astonishing.

He discusses the implications of all this brilliantly, making many shrewd observations. He remarks on the emergence of mushrooming cities where only villages stood a generation or two ago. He naturally stresses the demographic angle powerfully: “By 2050, about 40% of all the people under 18 in the world will be African, a proportion that will reach half by century’s end.” He comments on the lamentable lack of urban planning, with facilities for public transportation, and he urges planners to apply lessons learned in Asia.

I was struck by the way the African megalopolis region is divided between very different zones, depending on imperial memories, from an era sixty years back:

Perhaps the most important imperial legacy, though, is the insular national elites who, because of colonial history and the near-checkerboard way the countries alternate between English and French, pay scarce heed to each other. A Nigerian I met in Accra, for example, told me: “It wasn’t until I started spending time in Ghana recently that I realised Ghana isn’t our neighbour. Benin sits next to us, followed by Togo.”

As that last point about geographical sequence sometimes confuses even me, I chuckled.

I won’t rehearse French’s points in detail: read the article!

I would just add a couple of things. My main professional interest is religious, and French says little about this topic, at least in what I assume to be an extract from a far larger work. But this stretch of coast is also going to be home to one of the world’s heaviest concentrations of Christians, with very sizable Muslim communities. Nigeria alone (not just the coastal zone) should have 400 million people by 2050, roughly divided 50-50 between Christians and Muslims. Look to this megalopolis if you want to see where a large portion of the world’s Christians will be living in 2050, say, and imagine the conditions of such a mega-mega-city. We don’t use the word “giga-city” much yet, but maybe we should start. Think what the churches (and mosques) will need to do to maintain civilized existence.

There is also the historical dimension, with its powerful resonance for anyone who cares about the heritage of slavery. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, European maps of West Africa classified regions according to their economic staples. Exact names and definitions varied somewhat, but generally you had the Grain Coast, the Pepper Coast [now Liberia], the Ivory Coast, then the Gold Coast [Ghana], before arriving at the unabashedly-named Slave Coast. That last area, lying between the Volta River and the Lagos Lagoon, includes the modern-day countries of Benin and Togo, together with the far west of Nigeria, which together now stand at the heart of French’s coming “megalopolis”. The Benin city of Ouidah (Whydah) was a key emporium for the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and those residual memories still make it a harrowing place.

This has a current echo in popular culture. Prior to 1975, Benin was still called Dahomey, and that is a very evocative, and fraught, name in the history of the region. Dahomey is the setting for the deeply questionable recent film The Woman King, which drives so many historians up the wall. You can follow the arguments yourself, but the fundamental problem is that the film’s (Black African) historical heroes and heroines were in reality brutal slavers and slave traders, on a colossal scale. I quote an article in Reason: “To portray Dahomey as a kingdom of freedom fighters would be akin to producing a movie about the Confederacy as an anti-slavery republic, starring Robert E. Lee as the primary abolitionist.” And don’t get me started on those woman warriors of Dahomey and their central role in mass human sacrifice, another thoroughly-documented historical feature that is oddly absent from the film. Because The Woman King is such mendacious trash, it might even be over-qualified in the Oscar stakes.

By the way, another Guardian piece describes the film’s impact on Benin itself, where it plays to constantly sold-out crowds, who find it a source of historical pride. If that works for those good people, wonderful, but I wish it could be something close to actual history.

The Dahomey story offers more serious religious dimensions. Ouidah is also the spiritual heart of the Vodun religion, which under names like Voodoo has had its profound impact across the New World. In 1967, a seriously under-rated film version of Graham Greene’s novel The Comedians was notionally set in Haiti, but its spectacular scenes depicting “Haitian Voodoo” were filmed in Dahomey/Benin, and using actual modern-day Vodun. The Voodoo scenes still look amazing.

Benin’s capital, Porto Novo, has a spectacular Great Mosque built in Portuguese/Brazilian style, and the building tells a potent story. Among the vast numbers of slaves the Portuguese took to Brazil were many Muslims. Many retained their cultural identity and in 1835, Muslims staged an effective rising in the great slave port of São Salvador da Bahia. Although the government suppressed the insurrection, they decided that these Muslims were too dangerous to be kept in place, and they began a policy of repatriation that extended to emancipated slaves. Most of these Afro-Brazilians found their way to the former Slave Coast, where they built an enduring culture that borrowed heavily from those acquired styles and traditions. The Great Mosque itself was not completed until 1935 – the centennial of the revolt. It is a perfect monument to the idea of the Black Atlantic as a religious phenomenon.

Finally, I think of the very immediate repercussions of climate change in this specific area. Nigeria alone stands in real peril from such issues. In the country’s north and center, the main peril stems from lack of water and the spread of deserts. Damage to fishing resources and to drinking water endanger the livelihood of many millions. Threats to potable water are all the more serious in societies prone to infectious diseases, and the risk of sweeping new pandemics is high. Normally in such circumstances rural people flee ruined areas to seek some kind of salvation in major cities, which in such crises often witness sharp population growth. In Nigeria, the obvious destination would be Lagos, a city of some 20-25 million presently (and growing fast), and the heart of the country’s economic power.

But in this case, any such urban movement would be a dubious proposition. As is common around the world, major cities tend to develop on the seacoast or on major rivers, which makes them peculiarly sensitive to climate change. Lagos itself takes its name from the Portuguese word for “lakes” or “calm water,” suggesting its original ecological context. The city is desperately vulnerable to flooding and storm surges, which will become far worse in coming decades, to the point of making the city close to uninhabitable. Will Lagos even be there in 2100, at least in any sense that we might recognize today?

What will the religious consequences of all this be? Will we see new prophetic and apocalyptic movements arising to confront the threats from incensed Nature?

Nothing I say here is in any sense a criticism of Howard French. Rather, he just makes me think about so many issues!

Howard French is also the author of Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War (Liveright 2021). You can find an essay derived from that book in another Guardian column from 2021, under the title “Built on the bodies of slaves: how Africa was erased from the history of the modern world.” That is also well worth your attention.

There are already some rich visions of these African futures in science fiction. In her terrific Lagoon (2014), Nigerian-American Nnedi Okorafor imagines aliens landing on Earth to make contact with humanity, and where else should they land but the waters off Lagos?