What will the end of Roe v. Wade really mean for abortion in America? If the Supreme Court, as now expected, declares next month that there is no constitutional right to an abortion, it will be one of the most momentous events in the recent history of the court. This will be the moment for which the pro-life movement has been eagerly awaiting for decades and about which the reproductive rights movement has issued the most dire apocalyptic warnings.

Yet the practical results of this measure will fall considerably short of what either side expects. The end of Roe will not mean the end of legal abortion in the United States nor will it result in widespread deaths of women from coat hanger-induced self-abortions.

But what exactly will happen? In order to answer that question, we need to know what exactly happened as a result of Roe and its aftermath – and what various states are preparing to do now that the end of Roe appears imminent.

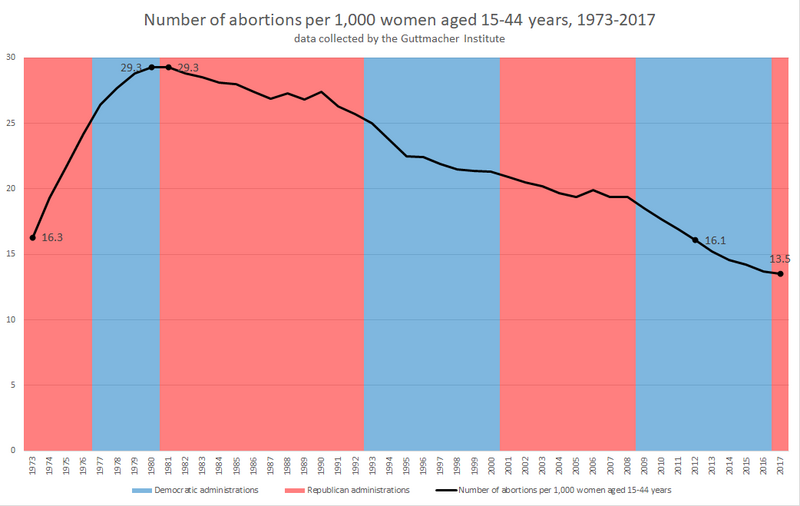

In this first installment in a multipart article series on the end of Roe v. Wade, I’ll examine Roe v. Wade in its historical context of the early 1970s and look at the effect that the decision had on abortion rates in the United States. And I’ll also examine why abortion rates have fallen so dramatically even without the formal reversal of Roe – which might lead one to ask whether the end of Roe will really have as much effect on abortion in the United States as either side anticipates.

What did American abortion law look like immediately before Roe v. Wade?

Roe v. Wade did not mark the beginning of legal abortion in the United States, so its reversal will not end abortion’s legality.

Before Roe v. Wade, there was no unified national policy on abortion, so each state had the right to establish its own abortion law. In 1972, the year before the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, abortion was legal for “therapeutic” reasons (rape and incest, suspected fetal deformity, and dangers to a woman’s health) in thirteen states and fully legal for elective abortions in four others. New York, the state with the most permissive abortion law, allowed elective abortions through the 24th week of pregnancy not only for state residents but also for non-residents. New York abortion doctors advertised their services in states where abortion was illegal, and some abortion rights groups helped women who wanted an abortion arrange transportation to New York and an overnight hotel stay for a low price. In 1972, there were 586,760 legal hospital abortions performed in the United States, of which about 200,000 were performed in New York.

A decade before that, abortion had been mostly illegal in the United States. Legal hospital abortions did occur, but mainly for psychiatric reasons. Since the law in most states before the mid-1960s allowed for abortions only when they were necessary to save a pregnant woman’s life, even the most permissive hospital abortion committees usually claimed that they offered therapeutic abortions only in cases when they claimed that forcing a woman to continue a pregnancy when she wanted an abortion might lead her to commit suicide. In addition, hundreds of thousands of women per year obtained illegal abortions, often from unlicensed “doctors” (who, in many cases, were medical school dropouts or others with some medical experience but no medical license) who worked for criminal syndicates. In New York City alone, illegal abortion providers associated with criminal syndicates were providing 250,000 illegal abortions per year in the 1940s, according to the estimate of the New York Times at the time.

But beginning in 1967, several states liberalized their abortion laws in order to provide more uniform standards and reduce the number of illegal abortions. When New York legalized all first and second-trimester abortions in 1970, the practice of abortion in New York moved from illegal facilities associated with criminal syndicates into public hospitals. Since New York had no residency requirement for obtaining abortions, any woman who could find a way to get to New York and pay for a hospital abortion could terminate her pregnancy – which meant that abortion was legally available for large numbers of women in the United States before Roe v. Wade, even if elective abortions still could not legally be performed in the majority of states.

How did Roe v. Wade change American abortion law?

Roe v. Wade declared that women had a constitutional right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester, states could restrict abortion only when the restrictions were necessary to protect a woman’s health. After the point of viability, states were permitted (though not required) to ban abortion altogether as long as they allowed exceptions for the purpose of protecting a woman’s life or health.

This sweeping ruling forced forty-six states to liberalize their abortion laws. At the beginning of 1973, the majority of states had allowed abortion only in cases in which it was necessary to save a woman’s life, and nearly all of the rest (in fact, all but four) had allowed abortion only for specific health-related or therapeutic reasons. Roe v. Wade required all states to allow legal elective abortions. Though a few states tried to resist, their resistance was quickly stopped by lower courts that applied the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe to the last hold-outs. By 1975, doctors were legally providing abortion in every state, and abortion clinics were operating in even the most socially conservative areas of the country.

The federal government also began funding abortions for poor women through Medicaid. By the late 1970s, approximately one-third of all abortions were Medicaid-funded.

By the beginning of the 1980s, there were nearly 1.6 million abortions per year performed in the United States – that is, one abortion for every two live births. It was the highest legal abortion rate in American history. And while the number of illegal abortions offered before Roe is difficult to determine, most estimates place it well under 1 million per year – which means that the legalization of abortion nationwide, combined with Medicaid funding for the procedure and the creation of multiple abortion clinics in every state, almost certainly increased the abortion rate. There were twice as many legal abortions per year at the beginning of the 1980s as there had been in 1973 (the first year in which abortion was legal nationwide) and about three times as many as there had been in 1972. It seems certain, therefore, that as legal affordable abortion services became available, the number of abortions per year was several hundred thousand more than it would have been otherwise.

Why did the abortion rate decrease after 1980?

In 1980, the Supreme Court upheld the Hyde Amendment (first passed in 1976), which prohibited the use of federal Medicaid funding for abortion except in cases when abortion was necessary to save a woman’s life. In terms of its practical impact on the abortion rate, this was probably the most effective form of national pro-life legislation ever passed. Several states (including New York and California) continued offering state Medicaid funding for abortion, but the majority of states did not. As a result, abortions became considerably more difficult for low-income women to obtain. The abortion rate, which had rapidly increased in the late 1970s, gradually declined in the 1980s and then began decreasing more rapidly in the 1990s, a decline that has continued to the present.

One consequence of the Hyde Amendment was a greater financial burden for poor women, who would either have to pay the cost of an abortion or the cost of giving birth and caring for a child – which is one reason why the amendment has been overwhelmingly unpopular among political progressives and civil rights advocates. Some African Americans (including Jesse Jackson) who had been pro-life advocates before the Hyde Amendment joined the pro-choice side and called for Medicaid funding of abortions shortly after the Supreme Court upheld the Hyde Amendment, leading to economic disparities in abortion access. The Hyde Amendment played a major role in aligning the pro-life movement with political conservatism. But at the same time, the amendment seems to have been highly effective in discouraging some lower-income women from getting abortions. Just as the abortion rate climbed rapidly in the mid-to-late 1970s as abortions were publicly funded, so abortion rates started dropping in the 1980s and 1990s as states began curtailing this funding.

But the Hyde Amendment was not the only reason for the decline in the abortion rate. Many pro-choice advocates believe that greater access to more effective forms of contraception led to declines in the abortion rate, and this is probably true – especially since the rapid decline in the abortion rate over the last ten years has also been accompanied by a simultaneous decline in birth rates.

In addition, pro-life state legislative efforts to restrict abortion without violating the basic parameters of Roe made abortion considerably more difficult to obtain in many conservative states and have prompted clinics to close. Twenty-six states, for example, currently require prospective abortion patients to wait at least 24 hours between the time they receive mandatory abortion counseling and the scheduled performance of their abortion procedure – a requirement that may deter women from getting abortions in cases where they live several hours from the nearest abortion clinic. Regulations on abortion clinics that were designed to shut down their operations – often known as Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) – escalated in the second decade of the 21st century, when hundreds of these regulations were passed, including laws mandating local hospital admitting privileges for abortion doctors and setting mandatory width requirements for hallways in abortion clinics. Altogether, states enacted 483 new restrictions on abortion between 2011 and 2019.

The number of abortion clinics plummeted in conservative areas of the country. In Alabama, there were forty-five abortion clinics in 1982, fourteen in 1996, five in 2017, and only three by 2017. Alabama’s abortion rate fell markedly, declining by 23 percent between 2014 and 2017 alone.

But this change was regional. Between 2011 and 2017, the South experienced a net loss of fifty abortion clinics, and the Midwest experienced a net loss of thirty-three, but the Northeast experienced a net gain of fifty-nine. As Republican states made it more difficult to obtain abortion, more liberal states expanded abortion access, both by providing Medicaid funding for the procedure and by making it easier for clinics to operate. Abortion rates were much higher in states that offered easy access to abortion than in states that did not. In 2017, the number of abortions per 1,000 women of childbearing age was 26.3 in New York, 16.4 in California, and 13.5 in Massachusetts, but only 6.4 in Alabama and 4.3 in Mississippi, according to statistics compiled by the Guttmacher Institute.

Still, though, abortion rates declined nationwide, even in states that expanded abortion availability. In much of the country, declines in the number of abortions were matched by a steep decline in birthrates as well, which may suggest that the abortion rate decline nationally was not so much the result of decreased access to abortion as it was increased access to contraception – which was the reproductive rights movement’s claim. Abortion rates in New York, for example, declined from 46.2 per 1,000 women of childbearing age in 1992 to less than 27 twenty-five years later, even though ease of access to abortion clinics in the state did not diminish during this period. The reproductive rights movement is probably correct, therefore, in believing that this decline was due largely to increased access to more effective contraceptives.

But in parts of the conservative South, abortion rates fell more quickly than birth rates, suggesting that in addition to the effect of increased contraceptive use, more stringent abortion regulations likely played a role in decreasing the incidence of abortion. The abortion rate in Texas, for example, decreased by 30 percent between 2011 and 2017, a period when the state implemented a rash of new abortion restrictions that shut down 25 clinics.

So, both the pro-life and pro-choice movements are correct in believing that their own approach to abortion reduction has been effective. In politically liberal pro-choice states, the reduction has probably occurred largely through increased contraceptive use, as many pro-choice advocates claim, and in politically conservative pro-life states, the reduction has come partly as a result of increased regulation of abortion, as pro-lifers claim.

Is the repeal of Roe necessary to return to pre-Roe abortion rates?

No, it’s not. In fact, we have already largely returned to a pre-Roe world even without the repeal of Roe v. Wade.

The United States now has a lower abortion rate than it has at any point since 1973. In 2017, the abortion rate was only 13.5 for every 1,000 women of childbearing age, compared to 16.3 in 1973. In 2017, there were 862,320 abortions in the United States – a figure that includes both medication and surgical abortions. By comparison, the United States had 745,000 legal abortions in 1973, approximately 900,000 in 1974, and more than 1 million per year in every year from 1975 through 2011. This means that the total number of abortions in the United States is now lower than it has been at any point since 1973, and its abortion rate is nearly as low as it was in 1972 (when the abortion rate was 13.16 per 1,000 women of childbearing age), the year before Roe v. Wade made abortion legal nationwide. (These figures, by the way, include the use of prescribed abortion pills, as well as surgical abortions, so they capture all legal abortions that occur through the medical system in the United States).

We have returned to a pre-Roe past in another respect as well: Both abortion rates and abortion availability vary more greatly by region than they have at any point since Roe v. Wade. In 2017, New York had an abortion rate of 26.3 per 1,000 women of childbearing age, compared to only 6.4 in Alabama and 4.3 in Mississippi. New York had 252 facilities that provided abortion, including 113 abortion clinics, and the number of its clinics was rapidly growing, with a 19 percent increase during the previous three years alone. By contrast, in Mississippi there was only one abortion clinic, which was staffed entirely by out-of-state doctors.

Pro-lifers in 1973 probably never imagined that they could return to pre-Roe abortion rates even without reversing Roe, but indeed, that is what happened. Yet for pro-lifers, overturning Roe has been the quest of a lifetime. But if that happens next month, what effect will it have on the abortion rate? Will it really result in the sweeping changes that pro-lifers have long expected? In an upcoming post, I’ll examine that question.

But for now, I’ll just say this: We are currently at a place where both abortion rate and abortion availability more closely resemble the United States in 1972 than the United States in 1974. So, if the goal in reversing Roe v. Wade is to return the United States to the way that it was in the year before Roe, we’re essentially already there. If the reversal of Roe will accomplish any reduction in the abortion rate beyond what we have currently experienced, it will have to push the United States not merely back to a pre-Roe era but to an era that was already gone even by 1972. And that might be more than what the Supreme Court can accomplish. Or is it?

I’ll take up that question in another post.