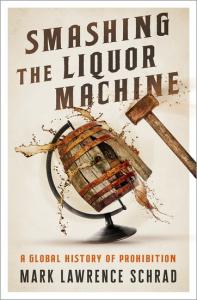

All historians are revisionists, but some of us are less cautious than others. I, for example, would be terrified to subtitle the introduction to one of my books, “Everything You Know about _____ Is Wrong.” But that’s precisely how Mark Lawrence Schrad begins his ambitious new history of the prohibition of alcohol, Smashing the Liquor Machine.

I’ve only just started in on Schrad, so if you want an appreciative but critical review of the full work, try Heath Carter’s at Christianity Today. But I’ve read enough to recognize how Schrad’s iconoclasm makes better sense of my own experience of lingering prohibitionist sentiment, and flipping ahead through future chapters only has me more excited to finish.

I’ve only just started in on Schrad, so if you want an appreciative but critical review of the full work, try Heath Carter’s at Christianity Today. But I’ve read enough to recognize how Schrad’s iconoclasm makes better sense of my own experience of lingering prohibitionist sentiment, and flipping ahead through future chapters only has me more excited to finish.

In part, that’s because of his astonishing scope. Schrad may start in Iowa, but his version of the story takes him everywhere from Africa to Asia, Belgium to Turkey. (In an earlier work, he examined “vodka politics” in Russia, the subject of the first chapter in Smashing the Liquor Machine.) Schrad rejects the notion that temperance was imposed on others by Anglo-American colonizers or missionaries, and even when he looks at the United States, he’s as interested in Native and African Americans as European settlers and their descendants.

“American exceptionalism is a lazy myth,” he warns, “and nowhere more so than in temperance history.” So he proceeds to do the kind of transnational, multilingual archival work that I’ve previously urged for the history of evangelicalism. While Schrad is attentive to cultural differences, his comparative analysis claims to uncover

a striking continuity: everywhere, the temperance-cum-prohibition movement harnessed the moral and material resources of organized religions into a broad-based, progressive movement to capture the instruments of legislation and statecraft against powerful, established political actors. In the United States as around the globe, temperance embodied a normative shift in which the exploitation of the weak, impoverished, and defenseless citizens for the benefit of the predatory capitalists and a predatory state were no longer considered appropriate.

So temperance makes sense as part of Lenin’s violent struggle against capitalism and Gandhi’s peaceful campaign against empire; and in the United States, it was inseparable from social movements like abolitionism and women’s suffrage.

So temperance makes sense as part of Lenin’s violent struggle against capitalism and Gandhi’s peaceful campaign against empire; and in the United States, it was inseparable from social movements like abolitionism and women’s suffrage.

Given my own familial and religious background, I was particularly interested to see Schrad present Sweden as an early illustration of how prohibition in Europe made important political strides — even if it never led to anything so radical as the 18th Amendment. In 1922 a proposed blanket prohibition didn’t even get a simple majority of Swedish voters, let alone the required two-thirds supermajority. Yet more moderate policies had already taken hold, with a system of individual liquor rationing enduring into the 1950s. The result was not only a change in consumption — Swedes still drank, but by the 20th century Sweden was no longer “the most drunken country in Europe” — but a peaceful political revolution.

Schrad credits the Swedish prohibitionist movement with helping to mobilize democracy in that kingdom, first by helping to channel “social-movement pressures into political activism” as part of an increasingly “robust civil society,” and then by strengthening the social democratic party (SAP) that emerged as a key force in the aftermath of Sweden’s industrial revolution. After adding a prohibition plank to its platform in 1911, the SAP nearly doubled its parliamentary presence. The Social Democrats held almost a third of Riksdag seats by 1917 and completed the shift to universal suffrage as part of a left-center coalition, then socialist leader Hjalmar Branting became prime minister in 1920 and called for the 1922 national referendum on prohibition.

It failed, but then Branting (unlike many in his party) wasn’t an absolutist. Instead, he could preside over what Schrad calls “the best of both worlds: dramatic reductions in alcohol-related harms, but without the infringements on an individual’s liberty to drink, or the bootlegging, corruption, and organized crime associated with prohibition.”

What made “such anti-alcoholism activism” necessary, argued Branting, was the need for the material and spiritual liberation of Sweden’s working classes. Originally trained as an astronomer, the prime minister backed a version of temperance that was “scientific and sociological, less sectarian and judgmental,” and even quipped that “Voltaire’s famous slogan about God could be applied to the temperance movement: if it did not exist, it would be necessary to invent it.”

Such figures seems to predominate in Schrad’s version of the prohibition story, though he doesn’t come off as hostile to religion. On the contrary, he opens with Carrie Nation and defends that “God-fearing Christian of the purest sort” against earlier historians’ sneers that she was “a Bible-thumping ‘crank,’ a ‘freak,’ a ‘lunatic,’ or a ‘puritanical killjoy,’ with all the baggage each of those terms carries.” And Schrad’s first chapter dedicated to the work of white American men opens with Baptist pastor Walter Rauschenbusch, calling his Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907) “fundamentally a temperance tract, fingering the liquor traffic as the foremost culprit of capitalism’s degeneracy.” Rauschenbusch’s values were “shared by millions of evangelical Christians across the country, and provided the soul not just of American progressivism but American prohibitionism, too.”

Schrad’s complaint here is not that traditional histories of prohibition “make a big to-do about religion,” but that they make the wrong “to-do” about it. To his mind, the key religious change in the late 19th and early 20th century was the willingness of Rauschenbusch and other Christian leaders “to move out of the pulpits and into the streets, organizing for both social and political activism” — just as Nation was significant because she believed that “justice, love, and benevolence were not things to be talked about on Sunday and forgotten the rest of the week.” Nation was not “seeking to legislate morality or ‘discipline’ individual behavior,” for the drinker was but a victim of the “true sinner… the enslaver of men: the drink seller.”

Schrad’s not wrong that such Christian prohibitionists “[upset] all of our two-dimensional stereotypes of evangelical Christianity.” But (on the slender evidence of my incomplete reading, at least) I wonder if he’s not a little too eager to make them a tolerably pious minority within his “broad-based, progressive movement to capture the instruments of legislation and statecraft,” rather than complicated figures whose religious fervor was directed at both social and personal sins.

To see what I mean, let’s go back to 19th century Sweden. Alongside the secular leftists that are Schrad’s chief concern and the Lutheran temperance advocates he mentions in passing, we also find religious radicals: Baptists, for whom prohibition was part of a larger reform.

The Swedish Baptist movement, said one of its first great American historians, began as a pietistic attempt to renew a society made dismal by the spiritual desiccation of its state church and the “deterioration in the moral fibre” of its people. But in Adolf Olson’s judgment, such problems were worsened by an

intemperance… so universal that, as one of the newspapers put it, “the distillation of whiskey is the corn of the Swedish nation; if you tread on it the whole nation shrieks”… the whole generation became saturated with whiskey. And the harvest did not fail: immorality, misery, crime and economic depression followed.

So while “the state church, the supposed defender of faith and morals, assumed a passive or, more often, hostile attitude” towards prohibitionists, “the temperance movement became an integral part of the religious revival that swept over the country, being especially promoted by pious and free-church people” like Olson’s Baptist forebears.

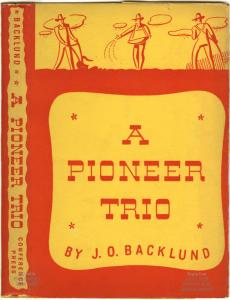

In his earlier hagiography of Swedish Baptist pioneers, J. O. Backlund made sure to establish the prohibitionist credentials of leaders like F. O. Nilsson, a sailor who organized temperance societies when he wasn’t preaching and distributing tracts, and Anders Wiberg, a former state church priest whose conversion and baptism only deepened his conviction that “no real advance, religious or moral, was possible until men and women were rid of their passion for strong drink.” One of Wiberg’s mentees, Carl Gustaf Lagergren, went on to edit a temperance newspaper and gave lectures that inspired the creation of over fifty temperance societies.

In his earlier hagiography of Swedish Baptist pioneers, J. O. Backlund made sure to establish the prohibitionist credentials of leaders like F. O. Nilsson, a sailor who organized temperance societies when he wasn’t preaching and distributing tracts, and Anders Wiberg, a former state church priest whose conversion and baptism only deepened his conviction that “no real advance, religious or moral, was possible until men and women were rid of their passion for strong drink.” One of Wiberg’s mentees, Carl Gustaf Lagergren, went on to edit a temperance newspaper and gave lectures that inspired the creation of over fifty temperance societies.

Nilsson was expelled from Sweden in 1851 and founded one of the first Swedish Baptist congregations in the United States; Lagergren came to this country in 1889 to take over leadership of the small seminary that eventually grew into my employer, Bethel University. Their support for temperance translated easily from the Old World to the New. When the Swedish Baptist General Conference published a new hymnal in 1903, the patriotic section actually opened with a set of six “sobriety songs.” Two paired anti-alcohol rhetoric with the national anthems of France and Finland, while others translated American temperance songs like Henry Clay Work’s “Come Home, Father,” which begs a hard-working, hard-drinking father to leave the saloon and stop neglecting his family. During the waning days of the 18th Amendment, one Bethel teacher went undercover to investigate an establishment near campus suspected to be “a combination hamburger joint, night club, and booze joint.” After the repeal of Prohibition, delegates to the denomination’s 1934-1935 meeting warned that “young people… constantly tempted by the open sale and clever advertisement of liquor” needed to be educated “as to the tragic physical and moral results of drinking and the benefits of total abstinence.”

Such anxieties faded, but never disappeared. When I came to Bethel in 2003, professors still had to join students and other employees in pledging annually not to consume alcohol. When the university ended the faculty prohibition five years later, I found myself on the other side of the debate from my mentor, G.W. Carlson. To me, the drinking ban seemed to be, at best, an unnecessary vestige of distant history and, at worst, an example of how Bethel’s Baptist Pietist ethos could still lapse into legalism. But GW resisted strongly. For him, a teetotaling faculty was a living reminder of Bethel’s roots in a religious revival that fused personal holiness with social reform. Not only did he see temperance as a freely-chosen means of maintaining the body as the “temple of the Holy Spirit,” but GW echoed Walter Rauschenbusch, one of his spiritual heroes: in his mind, alcohol abuse, in the 21st century or the 20th and 19th, was still inseparable from oppression, exploitation, neglect, and injustice.