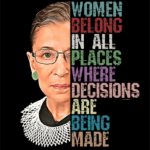

I’m happy to continue our mini-series of reflections on the legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, but let me encourage you to read Beth’s Monday post in addition to — or instead of — mine. It’s a powerful tribute to RBG that gives greater context for her achievements as a lawyer and judge.

Last Thursday, President Donald Trump went to the National Archives Museum to promote a more “pro-American” version of our national past. Criticizing those who “[rewrite] American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom,” Trump insisted that our founders “set in motion the unstoppable chain of events that abolished slavery, secured civil rights, defeated communism and fascism, and built the most fair, equal and prosperous nation in human history.”

One night later, we lost an American who did as much as anyone to secure those rights and build that equality. But Ruth Bader Ginsburg knew that there was nothing “unstoppable” about those achievements. She understood that the oppression woven into a story of liberation could only be unravelled with determination, dissent, and a knowledge of the complexity and contingency of history.

I hadn’t thought much about the importance of the past to Ginsburg until Saturday night, when students and faculty in our department gathered — outdoors, socially distanced — to observe Constitution Day by watching the 2018 documentary RBG.

As it tracked her early legal career, the film came to the 1973 case of Air Force lieutenant Sharron Frontiero, who had been denied housing and medical benefits available to male officers. “A person born female continues to be branded inferior for this congenital and unalterable condition of birth,” Ginsburg famously argued in her brief, then proceeded to illustrate her claim with examples drawn from American history. In a ten-page historical overview that quoted everyone from Thomas Jefferson and Dolley Madison to Sojourner Truth and Alexis de Tocqueville, she demonstrated how the law had denied equality to both women and African Americans:

Neither slaves nor married women had the legal capacity to hold property or to serve as guardians as their own children. Neither blacks nor women could hold office, serve on juries, or bring suit in their own names. Men controlled the behavior of both their slaves and their wives and had legally enforceable rights to their services without compensation.

While some progress was made over time, RBG concluded that “men viewing their world without rose-colored glasses would have noticed in the last century, as those who look will observe today, that no pedestal marks the place occupied by most women.” Over two decades later, having ascended to the nation’s highest court as its second female justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg continued to look at American history without nostalgia or despair.

Delivering the majority opinion in the landmark case U.S. v. Virginia (1996), which stopped Virginia Military Institute from continuing to deny admission to women, RBG noted that “today’s skeptical scrutiny of official action denying rights or opportunities based on sex responds to volumes of history.” Better than anyone, she understood historian Richard Morris’ argument that “a prime part of the history of our Constitution… is the story of the extension of constitutional rights and protections to people once ignored or excluded. VMI’s story continued as our comprehension of ‘We the People’ expanded.”

How did this phrase expand “to include all of humankind, to embrace all the people of this great nation?” Neither inevitable nor irreversible, this progress depended on the work of people like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was shaped not just by her knowledge of American history, but her Jewish heritage.

Speaking at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2004, RBG reflected on the history of another country where the law was “deployed by highly educated people… to facilitate oppression, slavery and mass murder.” It was in part because Americans “learned from Hitler’s racism” that they “embarked on a mission to end law-sanctioned discrimination in our own country.”

Earlier in that same talk, Ginsburg mentioned something we’ve heard often since her death: that she kept on the walls of her chambers an artistic rendering of the Hebrew words of Deuteronomy 16:20 — “Zedek, zedek, tirdof. Justice, justice shall you pursue.” But she surely knew that that command comes on the heels of another: “Remember that you were a slave in Egypt” (v 12). In the Torah, justice could only be pursued in the present if past injustice was remembered.

“In our long struggle for a more just world,” she concluded, “our memories are among our most powerful resources.” She hoped that the memory of the Holocaust would continue to “strengthen our resolve to aid those at home and abroad who suffer from injustice born of ignorance and intolerance, to combat crimes that stem from racism and prejudice, and to remain ever engaged in the quest for democracy and respect for the human dignity of all the world’s people.”

May her memory strengthen that resolve in us, and encourage us to look clearly and hopefully at the oppression and liberation we find in the past.