In an interview last week, evangelical activist Jim Wallis declared that “Trump is operating in the spirit of the anti-Christ.” It’s a sentiment that, while not unusual these days, does feature an edge that flies in the face of Wallis’s current establishment politics.

Indeed, Wallis was catapulted to celebrity status in the 2000s by his relationship with state senator—and soon-to-be American president—Barack Obama. After his 2005 bestselling book God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It, Wallis began to regularly appear as a guest on CNN and on comic Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show. He attended World Economic Forum meetings in Davos, Switzerland, each year. Sales from God’s Politics, which spent fifteen weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, infused Sojourners with cash. In 2006, old staffers, along with a new team of political organizers, fundraisers, and communications specialists, moved into gleaming new digs in Washington, D.C. The investment quickly paid off. In 2007, they bagged three of the top Democratic presidential candidates when Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, and Barack Obama participated in a Sojourners-sponsored CNN forum on faith and religious values. This was the same forum, according to Time editor Amy Sullivan, that several years before had barely attracted a single congressperson. Wallis had arrived at the center of American politics.

But his recent use of the language of anti-Christ does recall an earlier prophetic phase of the activist’s career. It began in the 1960s, when a young Wallis rebelled against an idyllic childhood that featured a loving family and “an abundance of warm affirmations, constant kudos, and great expectations for success.” But why, he began to ask, were the only blacks he saw in his Plymouth Brethren church missionary converts from Africa, not nearby inner-city Detroit?

Wallis’s politicization continued at Michigan State University, where he studied from 1967 to 1970. A stint in student government soon led to involvement in MSU’s Students for a Democratic Society chapter, which was rapidly radicalizing. Students were up in arms over the university’s heavy-handed treatment of protesters, revelations of campus ties to defense contractors and the CIA, the May 1970 Kent State shootings, and the U.S. military incursion into Cambodia. By his senior year Wallis enjoyed a national profile, claiming to be able to activate 10,000 people in a few hours’ time for protests. But he grew disillusioned by SDS’s “moral confusion” as it self-immolated, plagued by violence and fragmentation.

Wallis’s politicization continued at Michigan State University, where he studied from 1967 to 1970. A stint in student government soon led to involvement in MSU’s Students for a Democratic Society chapter, which was rapidly radicalizing. Students were up in arms over the university’s heavy-handed treatment of protesters, revelations of campus ties to defense contractors and the CIA, the May 1970 Kent State shootings, and the U.S. military incursion into Cambodia. By his senior year Wallis enjoyed a national profile, claiming to be able to activate 10,000 people in a few hours’ time for protests. But he grew disillusioned by SDS’s “moral confusion” as it self-immolated, plagued by violence and fragmentation.

Soon after, Wallis turned back to the source of his childhood faith, which he had abandoned while in college. “I started reading the New Testament again,” he recalled, “which I hadn’t done in many years, just on my own. What I began to see in the first three Gospels was a Jesus who stood with the poor and marginalized and who taught his followers to be peacemakers, a Jesus I had never heard much about in church but was now rediscovering.” This spiritual awakening, coupled with admiration for the nonviolent Martin Luther King, Jr., and the faith-rooted origins of the civil rights movement, led him to theological training at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, a rapidly growing conservative evangelical seminary in the northern suburbs of Chicago. He arrived ready to “take on the evangelical world with Jesus and the Bible.”

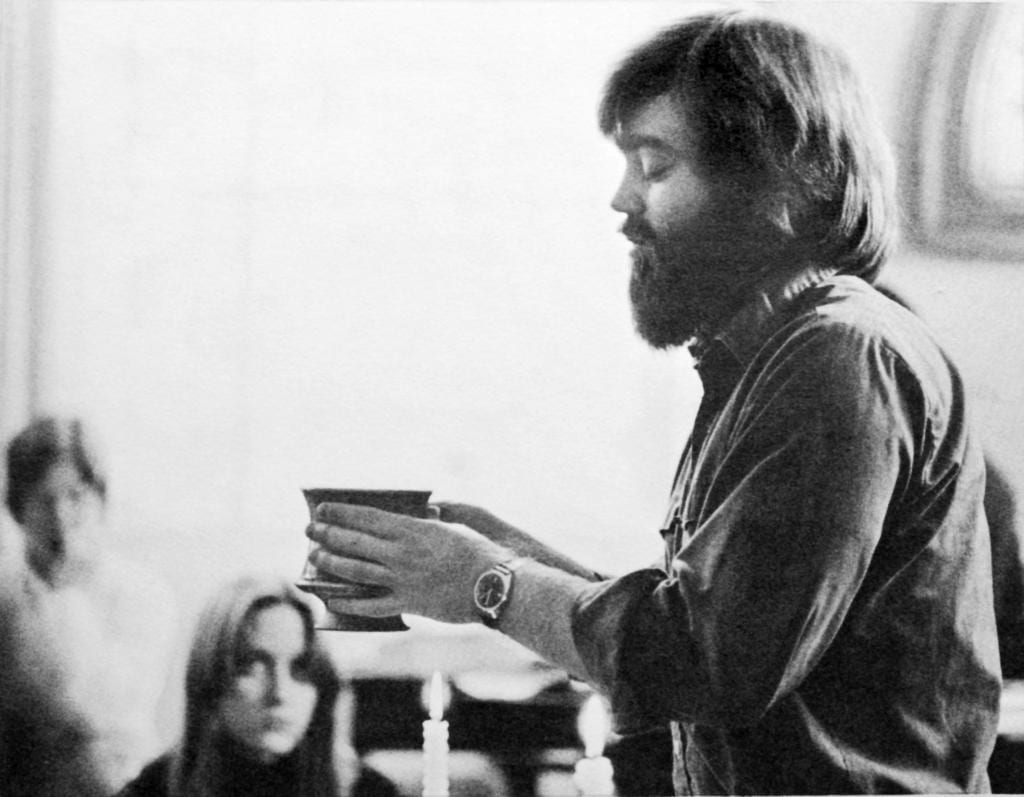

Wallis and his seminary friends—calling themselves the Post-Americans—began to agitate. Borrowing techniques from the left such as guerrilla theater, picketing, leafleting, and direct, personal confrontation, they pushed back against establishment evangelicalism. Christianity Today had denounced “picketing, demonstration, and boycott” in 1967, but Wallis contended that dissent was necessary to correct the status quo. Spiritual resources should be used to judge, not merely legitimate current conditions.

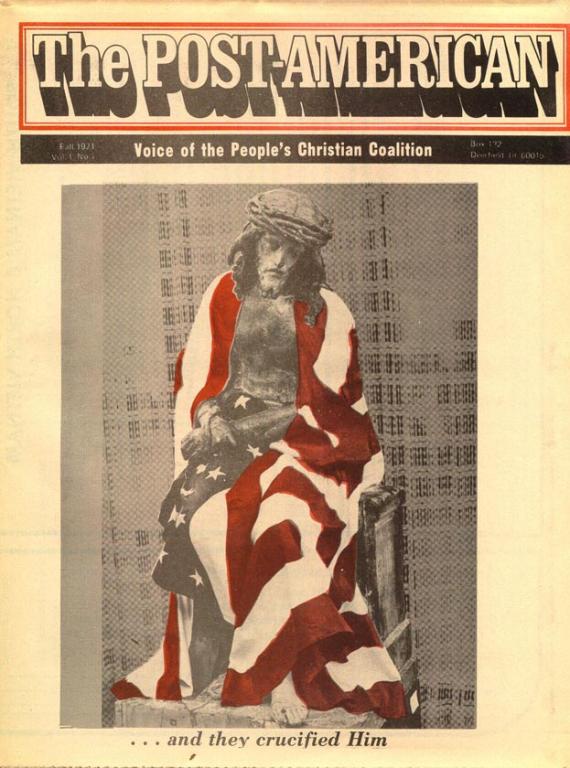

They began a tabloid called The Post-American. The first issue in the fall of 1971 featured a cover with Jesus wearing a crown of thorns and cuffed with an American flag that also covered his bruised body. America, the depiction implied, had re-crucified Christ. Inside, “A Joint Treaty of Peace between the People of the United States South Vietnam and North Vietnam” declared that the American and Vietnamese people were not enemies and called for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops. The “American captivity of the church,” Wallis continued, “has resulted in the disastrous equation of the American way of life with the Christian way of life.” Increasingly dismissing decorous evangelicalism as passé, even immoral, in the face of social injustice, they began to portray Jesus as a revolutionary figure, add a harder edge to protests, and display more urgency and exuberance as they took their faith and politics to the streets.

They began a tabloid called The Post-American. The first issue in the fall of 1971 featured a cover with Jesus wearing a crown of thorns and cuffed with an American flag that also covered his bruised body. America, the depiction implied, had re-crucified Christ. Inside, “A Joint Treaty of Peace between the People of the United States South Vietnam and North Vietnam” declared that the American and Vietnamese people were not enemies and called for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops. The “American captivity of the church,” Wallis continued, “has resulted in the disastrous equation of the American way of life with the Christian way of life.” Increasingly dismissing decorous evangelicalism as passé, even immoral, in the face of social injustice, they began to portray Jesus as a revolutionary figure, add a harder edge to protests, and display more urgency and exuberance as they took their faith and politics to the streets.

As the Post-American’s first issue indicated, these evangelical radicals tried to keep it theological. Wallis, said a former classmate, liked to rip out all the pages in the Bible that dealt with money and poverty, leaving only a tattered shell remaining, to make his point that social justice mattered. While others in the New Left made their case using sociological arguments, Wallis “made it theological” and insisted on scriptural justification for arguments.

Evil itself, the Post-Americans wrote, resides in bureaucratic capitalism and the military-industrial complex. Jim Wallis continued to use absolutist language to condemn the Vietnam War. Not a “mistake” or a “blunder,” as liberals often argued, the war was a “lie … a crime and a sin … that continues to poison the body politic.” Bob Sabath, describing American power as a satanic principality, coupled the Apostle John’s image of “principalities and powers” with the leftist fear of government power and economic bureaucracy. He exposited Romans 13, a passage in Scripture that urges submission to governing authorities, in the context of the thirteenth chapter of Revelation, a passage Wallis saw as declaring open resistance to the Roman Empire. “Here was the Christians’ first dictate against the hellish iniquities and arrogant nationalism of the world’s most powerful nation,” explained Sabath. In only thirty-five years, the early church had transformed from a law-abiding people, suggesting that “even a legitimate state … is always in danger of becoming satanic. There is an inevitable drift toward the demonic.”

Wallis grounded this hermeneutical judgment in the biblical creation account, writing that “supernatural beings were created for human good (in fact, we can’t function without them), but revolted and fell, with the consequence that they have an ever-present tendency to usurp God’s intended purpose for them and hold humans in bondage to their pretentions to universal sovereignty.” For radical evangelicals, good and evil were not abstract categories; they came to life in real supernatural demons grounded in the creation account in the biblical narrative.

Wallis grounded this hermeneutical judgment in the biblical creation account, writing that “supernatural beings were created for human good (in fact, we can’t function without them), but revolted and fell, with the consequence that they have an ever-present tendency to usurp God’s intended purpose for them and hold humans in bondage to their pretentions to universal sovereignty.” For radical evangelicals, good and evil were not abstract categories; they came to life in real supernatural demons grounded in the creation account in the biblical narrative.

The Post-Americans interpreted evil in very specific ways. They saw demons at work in the concentrated power of elite Latin American oligarchs, but most often in the “United States of Babylon.” Former Post-American Boyd Reese explained structural injustice in America to the InterVarsity chapter at NYU-Binghamton in terms of “principalities and powers.” Study notes from the early years of the Post-American community encouraged followers toward “resistance to the principalities of death” in the administration of Richard Nixon and corporate America. Joe Roos suggested that Watergate and the Vietnam War, which represented “the pinnacle of arrogance,” reaffirmed the role of Satan in temporal affairs. “The prince of this world,” Roos explained, “encourages and delights in the consequent suffering and moral decay.” That Post-Americans’ vitriolic attacks on the power elite of America met with equally contentious responses—“We’ve been the most assailed by people and institutions of wealth and power,” several Post-Americans complained to a Washington Post reporter in 1976—only confirmed their sense of embattlement at the hands of the principalities. A controlling metaphor of warfare between good and evil—“The church of Jesus Christ is at war with the systems of the world, not détente, ceasefire, or peaceful coexistence, but at war”—characterized radical evangelical conceptions of American society.

If the Post-Americans suggested that America had succumbed to the forces of evil, they nonetheless predicted ultimate victory. The larger war between good and evil would be won through the crucifixion, resurrection, and ultimate triumph of Christ over satanic forces in the universe. The cosmic implications of Christ extended beyond “the liberal … theology which reduced Jesus to a Galilean boy scout.” But “the work of Christ on the cross,” explained Post-American Boyd Reese, “would ultimately defeat the demonic nature of American power brokers, thus offering hope for social justice that secular messianisms could not.” Since there are “spiritual as well as political dimensions to the struggle for justice, with praying together one of the most radical political actions people can take,” Reese explained, “it will not be long until American power will have to answer to Christian prayer and protest.” Radical evangelicals fought alongside God as foot soldiers in a battle against American principalities.

It’s hard not to notice similarities in style between these radical evangelicals and the religious right. Both groups blurred lines between faith and politics. Indeed, this was precisely the point—to tie the sacred to the temporal so closely that the two were indistinguishable. Did Wallis and his comrades, who moved so contentiously into politics nearly a decade before the Reagan revolution, prefigure the political style of the religious right?

It’s hard not to notice similarities in style between these radical evangelicals and the religious right. Both groups blurred lines between faith and politics. Indeed, this was precisely the point—to tie the sacred to the temporal so closely that the two were indistinguishable. Did Wallis and his comrades, who moved so contentiously into politics nearly a decade before the Reagan revolution, prefigure the political style of the religious right?

That’s probably going too far, but it does seem clear that Wallis’s most recent invocation of the anti-Christ is not a promotional ploy. It is an authentic and deeply grounded application of a profoundly felt theology that has been with him since the 1960s. It’s an attempt, as he notes in his twelfth book Christ in Crisis: Why We Need to Reclaim Jesus, to ensure that “one’s identity in Christ precedes every other identity.”

Wallis’s rise to prominence was smoothed by his willingness to tamp down Manichean language. But during times of crisis—Watergate in the early 1970s, the rise of the religious right and the Reagan Revolution in the 1980s, and the Iraq War debacle and Islamophobia in the early 2000s—this more radical strain resurfaces. As Trump and white evangelicalism combine and self-destruct, there’s no question that we’re in another such moment now.