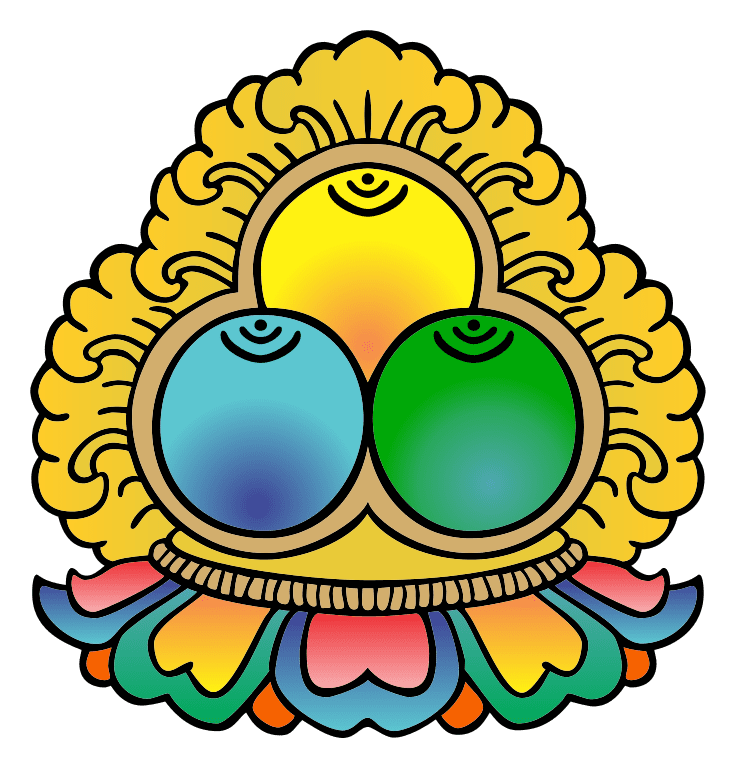

The Three Jewels (triratna in Sanskrit, tiratana in Pali) represent what for many is the quintessential hallmark of being or becoming a Buddhist: going for refuge. The refuges and jewels are: the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. The Awakened one, the Truth or his Teachings, and the four-fold community of lay men and women and monks and nuns. In some traditions, Buddha is expanded beyond the historical Buddha and his teachings to a more abstract sense of awakening. And the Sangha too can take on different meanings, but generaly it means “community” (of folks on the same path as me, from most beginning beginners to the Buddha/Buddhas).

In many traditional Theravadin ceremonies, taking the triple refuge (ti-sarana) is often chanted at the begining:

Buddham saranam gacchami.

Dhammam saranam gacchami.

Sangham saranam gacchami.

The translation is:

I go to the Buddha as a refuge. (word-by-word: To the Buddha, for refuge, I go)…

I go to the dhamma as a refuge.

I go to the sangha as a refuge.

The Buddha did not include a clause here demanding that other faiths be abandoned. Nor did he create a system of beliefs and practices that was fixed and immutable. The Buddhists of his time, and after, continued to hold beliefs and engage in practices beyond hist teachings (the dhamma).

As one story goes, the Buddha was asked near his time of death if the Vinaya – rules for monks and nuns that had developed over time – could be altered. The Buddha responded that “the minor rules could be changed, but not the major ones.” After some confusion in the community about which rules were minor and which were major, they decided to change none of them. As such, the developing, fluid, evolving nature of the Vinaya became static. But even that has undergone changes as different schools developed slightly different sets of rules and the interpretation of them has varied according to time and culture.

Even more so, the philosophical ideas of the Buddha have been open to interpretation and debate. Emptiness (sunyata) was not a terribly important aspect of the Buddha’s early teachings. But it was drawn into central importance several hundred years after his death in the “Perfection of Wisdom” (prajna-paramita) literature and “Middle Way” (madhyamaka) philosophy of Nagarjuna and others. The Buddha was also clear that language or the sounds of words had no intrinsic value or power: the teachings themselves must be understood and implemented for change to occur. Nonetheless, the Brahmanic (proto-Hindu) idea of mantras made its way into Buddhist thought and practice. The Buddha seemed to oppose guru-worship, instead establishing a community with basic rules of seniority and spiritual friendship (kalyana-mittas). Nonetheless, ideas of guru veneration crept in to several traditions.

All of this is to say that Buddhism has evolved. Or that there are many Buddhisms if one examines the distinct histories of the many threads of Buddhist development.

Today in Thailand there are often shrines to Brahma in or just outside of Buddhist temples. I am in Fuding, China now, and I’ve just learned that this Brahma statue has similarly made its way north, likely via Burma, into South China and is called “the four-faced Buddha.” There is one of these in the entrance shrine of the temple I’m at now. There is literally a Hindu god looking out over a courtyard in our Chan Buddhist temple.

In China and Taiwan, Daoist gods find similar place – and many Buddhist practitioners also go to Daoist temples for certain activities. In Japan there is a saying that one is, “born Shinto, married Christian, and dies a Buddhist,” as each religion has found a particular niche in the society. One doesn’t make a great leap (or conversion) from one religion to the other. One can still be involved in Shinto rituals throughout life. As Buddhism went to Tibet, the beliefs, practices, and gods there were not denied or shunned, but rather selectively incorporated into Buddhism.

Then Buddhism comes to “the West” – dominated by the exclusivist religious mores of Christianity. Here, to be “born a Jew, married a Christian, and die a Muslim” would involve clear shifts in religious allegiance.

And so, some Buddhists in the West project this demand of allegiance and exclusivity back into Buddhism. In this way, Buddhism is being co-opted by a culture of exclusive allegiance.

On the other hand, many Buddhists in the West continue the long Buddhist tradition of interacting with other faiths, even accepting dual-allegiance (and triple perhaps, even quadruple?). Terms such as Jubu (or Jewbu or similar) have arisen to signify Jewish-Buddhist affiliation. Christian-Buddhists, both Catholic and Protestant, have come forth out of this encounter. Secular Buddhists, too, represent a continuation of the Buddhist tradition of hybridity.

So while one goes to refuge in the three jewels as a Buddhist (and this is a fairly standard traditional definition of a Buddhist), one can also take part in other religious practices and beliefs without sacrificing any of their Buddhist-ness. Again, the idea of exclusivity seems much more a product of the exclusivity of Abrahamic faiths, which Westerners then assume apply to non-Abrahamic religions.

Of course this also brings to light the difficulty of religion as a category, but that is best left for another day.

May all who take refuge in awakening, truth, and community, be they “Buddhist” or otherwise, find peace and fulfillment in their journey.